In 2009 Glenn Kurtz was cleaning out a closet in his parents’ Florida home when he happened upon home movies shot by his grandfather, David Kurtz, on a European vacation in 1938. Embedded in the 14 minutes of footage was an extraordinary three minutes capturing snippets of ordinary life in a small, predominantly Jewish Polish town. That discovery launched Kurtz on a four-year odyssey that took him to Poland and Israel, and led him to research in which he identified a number of the people in the film. Kurtz records the compelling results of his search for this destroyed world of prewar Polish Jewry in his book “Three Minutes in Poland: Discovering a Lost World in a 1938 Family Film.”

Leora Tec, founder of Bridge to Poland, regularly leads study tours showcasing Polish non-Jews memorializing Jewish life in Poland. Tec, a Jew of Polish descent and the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, first went to Poland in 2005 with her mother, the renowned Holocaust scholar Nechama Tec. The elder Tec, who was born in Lublin, focuses her work on Polish resistance to the Holocaust, as well as the rescue of Jews by Poles.

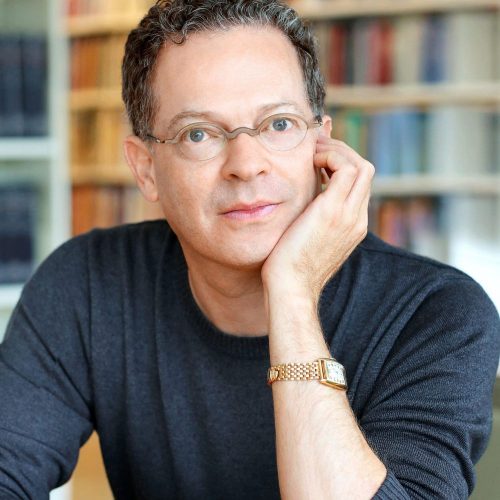

Both Kurtz and Tec were recently at Hebrew College to share their diverse yet profound connection to Poland in a presentation entitled, “Poland: Uncovering the Past and Revealing the Future.” Unlike Tec, Kurtz’s story begins in America. His grandparents were part of the great wave of Jewish immigrants who came to the United States in the 1890s. “[My grandparents] didn’t remember the old world specifically, but nevertheless stayed connected to it. But their story,” Kurtz emphasized, “is an American story. Through hard luck and perseverance, by the 1920s they had worked themselves into the middle class. And by the 1930s they were in a position to travel.” Kurtz’s grandfather died before he was born, and like many immigrants intent on assimilating into American life, his grandmother never spoke about her childhood in Poland.

Similarly, Tec’s mother did not speak about her Holocaust past for 30 years. But in the late 1970s she engaged with her memories of surviving the war as a hidden child in a memoir. It wasn’t until Nechama Tec published “Dry Tears: The Story of a Lost Childhood” that Leora learned the extent of her mother’s story. When Tec returned to Poland for the second time in 2007, she was ready to embark on a deeper exploration of her family’s history in Poland.

Tec noted that she often encounters people who have a strong animosity toward Poland. She frequently hears remarks that the Poles were worse than the Germans and that Jews have no reason to travel to Poland. For some, contemporary Jewish life is like a Potemkin village, only on display for tourists. Others are ambivalent or worry that going to Poland begs the question that framed Tec’s presentation: “Is it possible for Jews of Polish descent to walk into Poland and find anything beyond loss?”

David Kurtz’s footage turns out to pay homage to his hometown of Nasielsk. Just 35 miles northwest of Warsaw, the town, on the cusp of modernity, was also home to a Hasidic community, religious schools and a number of synagogues. “The first thing you think of when you see this [film] is that we know what they don’t know,” Kurtz said. “It’s what gives the film its tremendous power and poignancy. It captures a perfectly exciting day when Americans came to visit, but we know how terribly brief their future was.”

Kurtz’s lucky break in his research came when the granddaughter of a survivor from Nasielsk happened to see the film online and recognized her grandfather, Maurice Chandler, as a 13-year-old. Chandler was still alive at 92 and blessed with a prodigious memory. He was able to identify a number of people in the film for Kurtz. With actual names in hand, Kurtz tracked down a number of those survivors through arduous legwork and sifting through extensive archives.

At the center of Tec’s trips to Poland was her burgeoning friendship with two non-Jewish Poles dedicated to preserving the memory of Poland’s Jews. Witek Dabrowski and Tomek Pietrasiewicz joined forces to found a cultural center and theater in Lublin called the Brama Grodzka Teatr NN—a place devoted to preserving Jewish life and memory in the city of Lublin. Before the war there were 43,000 Jews in Lublin. Today only 40 Jews live there. Tec’s friendship with Dabrowski and Pietrasiewicz not only allowed her to delve into the richness of Lublin’s prewar Jewish life, it also led her to meet the daughter of the family that sheltered her mother, aunt and grandparents during the war. For 65 years this Polish woman had saved photographs of Tec’s family.

Tec says that on the study tours she leads, participants are frequently surprised at how colorful a city Krakow is. “I wonder,” she noted, “why the Poland of our times is sometimes a Poland of grainy black-and-white archival footage that has not gone beyond World War II and into a colorful modern country. What keeps it in the past in our minds?”

Perhaps David Kurtz’s footage can offer some answers. It portrays a jocularity as people vie to get into the frame. It shows men and women and children enjoying the attention of an American tourist with his camera. But perhaps most important, two-thirds of the film is in color, giving texture and vibrancy to a world forever gone.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE