Jill Ebstein had an ironclad rule when she was compiling the second anthology in her “At My Pace” series: Do not disrespect your mother. It was an essential directive when putting together a book about lessons that moms have handed down to children. That’s not to say the 38 essays that comprise “At My Pace: Lessons From Our Mothers” don’t mine difficult material. As Ebstein recently explained during an interview with JewishBoston: “I asked each contributor to show gratitude in some way for his or her mother and to put her struggles in context. If a writer could not get to that point, the book was not for him or her.”

“Lessons From Our Mothers” follows a successful first volume, “At My Pace: Ordinary Women Tell Their Extraordinary Stories,” which, said Ebstein, “was a response to Sheryl Sandberg’s book, ‘Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead.’ Only I was saying if you don’t want to lean in because you don’t want to be speeding on the autobahn of life, that’s OK. It’s more than acceptable to have a twisting path or to even take a U-turn. This was a chance for women for whom Sandberg’s story didn’t resonate to tell their own tales of resilience, reinvention and a resetting of perspectives.” Ebstein herself is the principal of a successful marketing firm who balanced a career with raising three children.

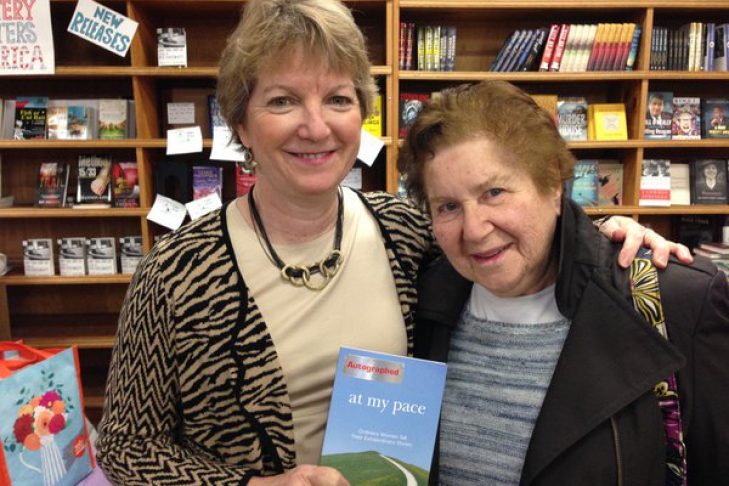

For Ebstein, though, this second installment was born of love for her mother, Rosyne Gardenswartz. Gardenswartz was on the verge of death last January when Ebstein decided she “wanted to write a piece that would explain one lesson that my mother gave me that affected me for my entire life. That piece turned out to be about [her] devotion to lifelong learning. When [she] was 80 she began a Jewish adult education program. As I wrote in my essay, her classmates were so impressed with her dedication to her studies they gave her a rolling backpack; that image says so much.”

Gardenswartz’s health improved and she returned to reading books and engaging in the world. Ebstein had hoped to put a copy of “Lessons From Our Mothers” in her mother’s hands before she died, but Rosyne Gardenswartz died last October on Rosh Hashanah at the age of 92. “I worked on the book from February to September,” said Ebstein. It was “a short, intense window” during which she edited pieces written by sons and daughters who ranged in age from their 20s to their 70s.

Throughout the editorial process, Ebstein was an involved editor. She noted: “In some pieces I would help a writer parse what they were trying to say, and they would go off and write. Others needed my help getting started, and quite often people got stuck in the middle and we worked hard to keep going.”

Ebstein also gave her writers a lot of latitude if they needed to explore difficult relationships with their mothers. “It was new terrain for me since I had such a wonderful relationship with my mother,” she said. “But in the thick of editing the book, I loved [discovering] how complex we all are. The cover picture of a fledgling giving a flower back to its mother reflects that complexity. For some contributors, it’s a symbol of gratitude; for others it’s an olive branch.”

Martin Abramowitz’s essay reflects on his mother’s decision not to tell him that his father had died. Abramowitz, who was a young child at the time, sensed that something was amiss when he was told his father was recuperating in Florida after a long illness. Abramowitz was able to reach a point many years later where he understood his mother, and even came to love and accept her, despite the lifelong difficulties her actions caused him.

Then there are the small things a mother does that are the foundations of loving memories. Marcia Katz Slotnick recalls that her mother, Anne, never left the house, and later her nursing home, without putting on lipstick. Elyse Friedman remembers her mother’s fondness for pineapple and her own resistance to the fruit until she finally enjoyed it in her mother’s honor on a Hawaiian vacation. “Little details,” said Ebstein, “can be both an irritant or an inspiration. They’re emotional triggers and also make you wonder, ‘What’s the one thing I did for my kids that they will cherish?’ We don’t need to give our kids an epic amount of things; it’s the little things that impress them.”

Jill Ebstein and some of the book’s contributors will be speaking and reading on Jan. 12 at 8 p.m. at Temple Emanuel in Newton.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE