William Shakespeare wrote almost 40 plays that have inspired countless adaptations and interpretations over the centuries. The latest incarnation of this literary exercise has contemporary writers reimagining and novelizing a Shakespeare play of their choice.

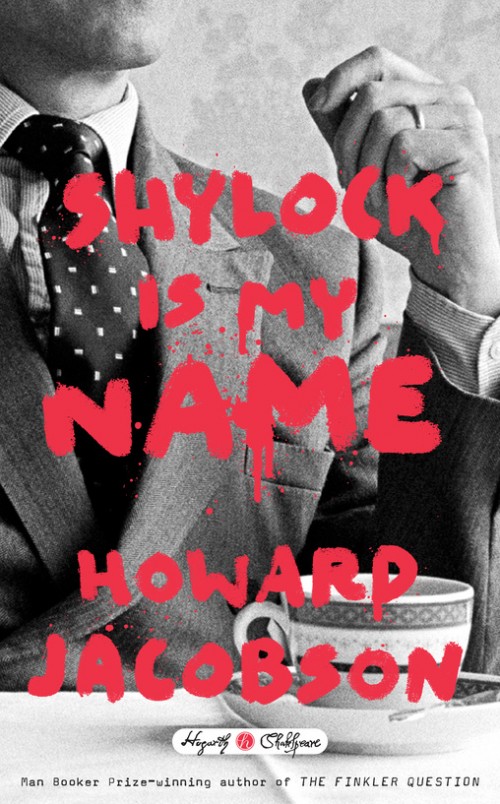

At first glance, it seems that “The Merchant of Venice” would be a natural fit for the English novelist Howard Jacobson. For more than a decade Jacobson has been a keen observer of Jews and non-Jews in Great Britain, which culminated in his winning the 2010 Man Booker Prize for “The Finkler Question.” In that novel he explored the relationship between an Englishman who wants to be a Jew and a Jew whose own Jewishness embarrasses him.

While Jacobson’s newly published novel, “Shylock Is My Name,” owes an obvious debt to “The Merchant of Venice,” adapting the play was not his first choice. In a recent email exchange he explained: “‘The Merchant of Venice’ wasn’t my favorite play. I have never lectured or written about it. If anything, I’d shied away from it. To my sense, remembering it from school, it wasn’t so much a problem play as an issue play.”

Jacobson, who notes that his work “does so often grapple with Jewish questions,” was looking for a break from those existential inquiries when he agreed to take on a Shakespeare play. Although he would have preferred to “tackle ‘Hamlet,’” he says, “the minute I reread [“The Merchant of Venice”] it came alive in new ways to me. I’d forgotten the energy in which Shylock is invested from the minute we first see him. Indeed, I’d never grasped what a towering presence he has for all his faults.”

Jacobson’s dark satire encompasses his argument that Shakespeare was more sympathetic than bigoted toward Shylock. “The play has inspired me to write in that way of Shylock,” Jacobson asserts. “I don’t make him moving in spite of the play, but in the spirit of the play. It goes beyond ‘sympathy,’ I think. Shakespeare makes Shylock live. I hear him, see him, note the strange way he talks and listens, become entangled in his passions and motivations even when we wish he would find another way to act.”

Jacobson is also quick to point out that the anti-Semitism that readers and audiences have encountered in “The Merchant of Venice” is more likely a reflection of their own prejudice. He notes that Shakespeare writes about the Venetian non-Jews, “with a cold contempt.” He says that interpretation of the play “licensed me to have satiric fun with [those Venetians]. In writing about Shylock himself, however, the tragic note seemed to me to be the one to strike.”

Just as Shylock dominates “The Merchant of Venice,” his doppelganger Simon Strulovich equally anchors “Shylock Is My Name.” A stand-in for Shylock, Strulovich is a rich Jewish philanthropist and art collector who endlessly worries about his beautiful, wild, teenage daughter, Beatrice. In the novel’s opening scene in a Jewish cemetery in Cheshire, Strulovich meets Shylock, who is still incredulously alive after 400 years. From the outset, Jacobson is playing with both the Jewish and Christian archetypes of the wandering Jew and a soul doomed to purgatory.

Shylock soon installs himself as Strulovich’s houseguest and their lives become eerily similar. When Beatrice runs away to Venice with the handsome, not-too-bright footballer Gratan, infamous for giving a Nazi salute on the field, it’s a plot line straight from the Shakespeare play when Jessica flees with Lorenzo. And when Strulovich tells Gratan that he will never allow Beatrice to marry the footballer unless he is circumcised, Jacobson has created the modern equivalent of Shylock’s “pound of flesh.”

“Notes are struck here,” Jacobson says, “and there in the play give a clue to Shylock the man, the widower, the husband to a wife he loved and father to a daughter to whom he is unable to give guidance and show love. I simply take my cue from those, imagining him still in conversation with his dead wife, still finding it hard to forgive Jessica her cruel perfidy, still wondering if it ever really was his intention from the start to take that pound of flesh, and whether he would have taken it had the court not found against his doing so.”

The play remains shadowed by the notion of the “Jewish question”—that same question looming large in much of Jacobson’s fiction. In “Shylock Is My Name,” Jacobson decries the subtleties of British anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism. He gives urgent voice to Jewish continuity, ancient and modern covenants and even circumcision. It is a performance that would have impressed Shakespeare himself.

Sponsored by the Jewish Arts Collaborative and Commonwealth Shakespeare Company, author Howard Jacobson will appear at Congregation Kehillath Israel in Brookline on Tuesday, March 22, at 7:30 p.m., with Pulitzer Prize-winner Stephen Greenblatt, author of several books on Shakespeare. Writer Jonathan Wilson will interview them. Click here for more information.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE