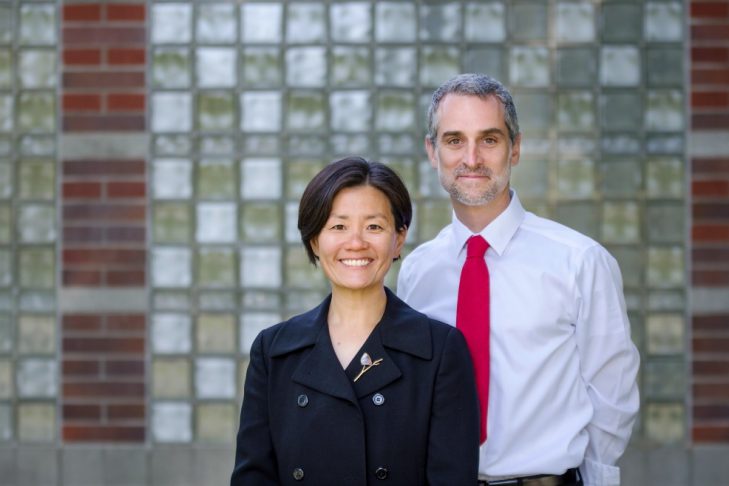

Helen Kim and Noah Leavitt are the authors of “JewAsian: Race, Religion, and Identity for America’s Newest Jews,” the first book-length study of Jewish-Asian couples and their children. While the two sociologists, who are married and professors at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Wash., have a personal stake in the subject, they have also observed that as a Jewish-Asian couple they are far from alone in raising their children as Jews. In the book, the couple’s research on Jewish-Asian families is encapsulated in interviews and extensive studies on the subject.

Keren McGinity, director of Interfaith Families Jewish Engagement at Hebrew College, notes: “‘JewAsian’ is groundbreaking because it’s the first book to complicate the intermarriage narrative by looking at it through the trifold lens of ethnicity, race and religion. Kim and Leavitt’s work highlights important new ways of understanding Jewish-American, Asian-American and Jew-Asian identities, challenging dominant racial, ethnic and interfaith marriage discourses in the process. I am thrilled to have it on my syllabus for the course ‘Jewish Intermarriage in the Modern American Context’ at Hebrew College this fall.”

Kim and Leavitt recently talked to JewishBoston about their new book and their family life.

What are some of the reasons Jews and Asians gravitate to each other?

Kim: From the perspective of our interviewees, they understand the non-individual connections as predominantly rooted in a shared set of values. The ones more frequently mentioned were the emphasis on education and a tight-knit family. A lot of people also mentioned work ethic and respect for elders. Those were the predominant reasons that shone through in terms of the connection at the level of values. If we look a bit further afield, Jews and Asians often live in the same communities. They go to the same schools and they work in the same places. Aside from values, these are points of connection that bring Jewish-Americans and Asian-Americans together.

What has your Jewish journey been like?

Kim: I am the child of Korean immigrant parents, and I was born in California. I chose to convert [to Judaism] in December 2015, and I really see myself reflected in the American-Jewish community, especially with the increasing attention paid to Jews of color and Jews who don’t fit the white Ashkenazi mold, which is often what we see in the United States. I see that discussion and presentation of the Jewish community really changing in very significant ways.

You’re raising two Jewish-Asian children—Ari, 8, and Talia, 5. What sorts of questions do you anticipate they will have?

Leavitt: This book was very personal for Helen and me. A lot of the investigation we did pointed to how we parent and help two young people come together with all these aspects of their backgrounds in one little body. What we heard when we asked the mixed-race millennials was that they wanted their parents to provide all of the streams of their heritages, including traditions and cultural insights, and let the kids sort them out.

Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan are perhaps one of the most famous Jewish-Asian couples. What was the Jewish community’s reaction to their marriage?

Leavitt: One of the reasons we felt strongly about showcasing the story of their relationship early on [in the book] was not so much for the couple themselves, but for what turned out to be an enormous variety of reactions to their marriage. Taking a quick trip to the blogosphere showed us everything from huge enthusiasm about “love conquers all” or “technology will help break down barriers” or “people who pursue education can always find love” to the other end of the spectrum, which included racist, stereotypical, reductionist views, especially about Dr. Chan. There were so many assumptions made about her because of her racial presentation that were very negative and led people to make negative, biting observations about them getting together.

From reading “JewAsian” I get the sense that Asian spouses struggle with transmitting their heritage to their children. Why is that?

You surveyed 39 young adults of Jewish-Asian heritage, the majority of whom identified more with their Jewish heritage. Why do you think that is?

Leavitt: Their identity began with their presentation to the world as multiracial. They experience situations where people challenge or question them; therefore, their response is almost always to increase their Jewish understanding and their Jewish practice. As they get older, people ask them, “Are you half Jewish or do you have a connection to Judaism?” Of course they do. They draw on their Jewish connections to respond, educate and inform the people questioning them with a broader understanding about Jews in America. On one hand, a lot of the young people we identified are frustrated about defending their Jewish authenticity regularly, but on the other hand they approach these situations as productive and hopeful interactions, because they see themselves as being able to increase or expand what people in America think Jews are and understand the Jewish community to be.

What’s your Jewish community in Walla Walla like?

Kim: We like to think of it as frontier Judaism. We belong to a small, lay-led congregation associated with the Reform movement. Our membership is roughly 35 families. We also have individuals who come to Walla Walla with their own histories of Jewish practice and denominational affiliation. Noah and I host a monthly Shabbat gathering of Jewish families with kids under the age of 8. It brings in a lot of Jews and Jewish families not necessarily associated with a congregation in town. [Our guests] are predominantly interfaith families.

Leavitt: By providing this regular chance for people to get together around Jewish practice in a celebratory, positive way, it has fostered Jewish learning and activity in these households outside of the monthly Shabbat dinner. It’s a good reminder that when the Jewish community is open to families who may have a low level of Jewish practice or understanding of Judaism, inviting them in can very often catalyze and increase that, and it doesn’t dilute the Judaism that is there.