My homework assignment was to consider the 1903 Uganda Proposal brought before the Zionist Congress to make the case for a Jewish homeland in Uganda. I was in seventh grade at a Jewish day school, and I advocated for settling in Uganda. I reasoned that any place that Jews could be together constituted a homeland, articulating a kind of “safety in numbers” mentality. But in the end my thesis didn’t please my teacher. Every morning during prayers we turned east toward Jerusalem. Like the Uganda Proposal, my argument failed to consider thousands of years of Jewish yearning for Zion.

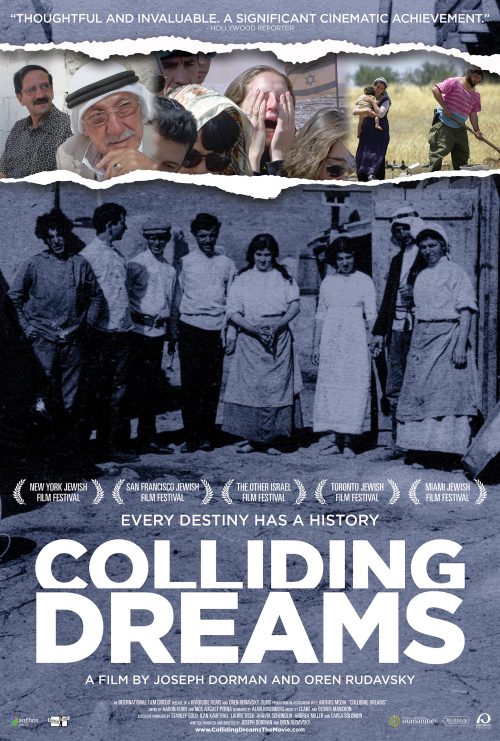

Oren Rudavsky and Joseph Dorman take on the nearly impossible task of capturing that yearning by presenting the history of Zionism in a two-hour film called “Colliding Dreams.” The two directors admirably succeed in reigning in a vast subject complicated with multiple viewpoints. In a recent conversation with JewishBoston, Rudavsky noted that “Colliding Dreams” embraced a subject very close to his heart. “Making this film was something I wanted to do in one form or another for a very long time,” he says. “But it got more complicated as we made it. There were so many perspectives on Zionism, [including those from] Jewish, Palestinian, right wing, left wing and settlers.”

Rudavsky’s challenge was to find a workable arc for the film while also aiming to keep the film comprehensive. “There were all sorts of [historical narratives] we could have gotten into,” he says. “But there were two main yet different kinds of Zionism—the whole land versus a land for the Jews—and that became the through-line with the Palestinians chiming in.”

Rudavsky traces his interest, indeed his affection, for Zionism, back to his childhood. For a decade, his father was the rabbi of Temple Sinai in Brookline, and he attended Solomon Schechter Day School of Greater Boston in the mid-1960s. “Hebrew was my father’s religion more than anything else,” Rudavsky says. His parents met at a Zionist school in Brooklyn named for Theodore Herzl, the father of modern Zionism. One of the filmmaker’s earliest memories was of the Six-Day War. “I was in fourth grade and one of the teachers was Israeli. I remember listening to the radio and seeing her crying because of the war. That scene is deeply imbedded in my memory, as well as how worried people were about what was going to happen.”

The next year, 1968, Rudavsky made his first visit to Israel. He remembers taking the trip with his family in the afterglow of Israel’s victory. It was also a time when Israel started to transition away from its David versus Goliath image to become a country suddenly involved in an occupation. Despite the country’s new political realities, Rudavsky notes that even in 1968 there was still a feeling that peace was in the offing. “You would walk through the old shuk in Jerusalem and have a sense that everything is OK,” he says. “It was just not the early [positive] experiences [between Arabs and Jews] in the 1920s.”

Rudavsky is referring to the photographs and footage in the film that show Jews and Arabs living, working and even celebrating together in the early 20th-century Palestine. But one of the 30-plus interviewees in the film captures the pervasive feeling of doom in those images when he wryly observes, “Palestine is like a beautiful girl, except that the girl is already engaged.”

Rudavsky explains: “There were Arab intellectuals as early as 1905 who were predicting the future, and there were Jews, including Ahad Ha’am, a Zionist thinker, who saw that there were Arabs in Palestine. But a people who, on the one hand, are experiencing pogroms, and are social idealists and radicals on the other hand, saw an opportunity and a possibility of rebirth. It’s a little bit like love; you believe what you want to believe, and you see what you want to see.”

Despite the personal biases the filmmakers and the audience inevitably bring to a film like “Colliding Dreams,” Rudavsky and Dorman create room for moderate voices to be heard alongside more extreme views. The result, Rudavsky comments, is that, “there is no resolution in the film. It’s a film meant to be a challenge to all of us who are willing to consider our prejudices. Unfortunately, most people are so dug into their positions they’re only looking for sustenance for their own points of view.”

Rudavsky is hesitant to make any predictions about Israel’s future. He only offers that the film ends on author Hillel Halkin’s provocative assertion that if Israel doesn’t succeed, the Jewish people don’t deserve to go on. “We could have ended [the film] on a brighter note, but we meant to challenge people,” he says. “We all have a part to play in Israel’s tikkun.”

That is an apt coda to a film that features Israeli playwright Motti Lerner explaining tikkun, or fixing: “Tikkun is a word that doesn’t exist in any other language. It’s a very spiritual world. Tikkun is a whole process that takes years. How do you reform yourself after you’ve been broken?”

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE