Jose Antonio Vargas came to America undocumented at the age of 12. That was 25 years ago. Although he is still undocumented, Vargas graduated college and went on to a Pulitzer Prize-winning career as a journalist. In 2011, he published an important personal essay in The New York Times Magazine, in which he revealed his immigration status. He has said coming out as undocumented was harder than coming out as gay.

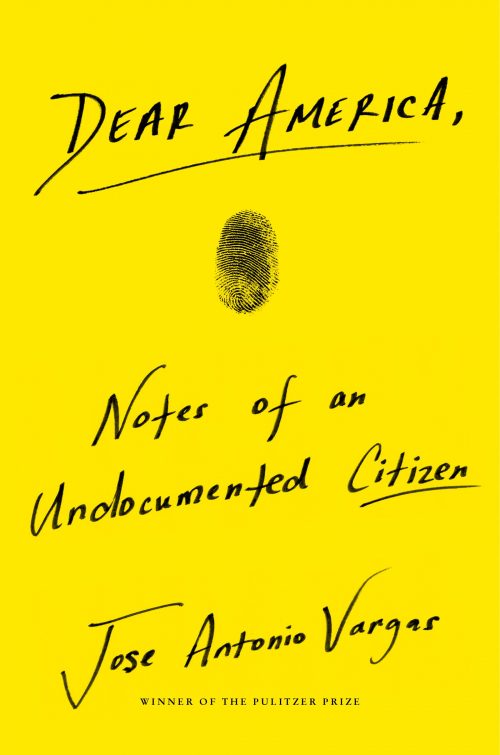

Vargas has a new memoir called “Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen,” in which he shares his life story, as well as traces the recent history of immigration in America. Vargas recently spoke to JewishBoston by phone about his hopes and dreams as an undocumented immigrant, his Filipino identity and his non-profit organization Define American.

Vargas will discuss his book at Brookline Village Library on Thursday, Oct. 11, at 6:30 p.m.

In 2011, Bill O’Reilly called you “the most famous illegal in America.” Are you worried about being deported?

I’ve had to worry about my immigration status since I was 16. When I was 30, I thought, I can’t worry about this anymore. The fear is still there. I can be deported any time. But I’ve come to peace with the fact that I don’t have control over that. But I do have control over what I do. One of the reasons I wrote this book—which, by the way, people thought was going to be an angry, anti-Trump book—was that I wanted to get into the mental health conversation we rarely have among immigrant communities. I wanted to write about DACA—Dreamers—about how low they feel, wondering every two years if the government will renew their status. I was a “dreamer” before there was a DREAM Act.

You say this book is about a particular kind of homelessness. What do you mean by that?

I grew up in the Bay Area. I went to school in San Francisco, and I’m very aware of what the homeless crisis looks like. I was initially afraid to use the term. I didn’t want to make a comparison that couldn’t hold. But then I started thinking about my own psyche, and there was no other kind of word or concept for it that would describe my contradictory feelings about being here. In the Jewish faith, a Jewish friend said to me, “We’re passionate about immigration because the whole thing is about home.” Jewish people bring something special to that conversation of home. Traveling across the country, I have met many Jewish people and encountered Jewish organizations that are places of welcome.

You came to the U.S. when you were 12 years old and attended middle school in Mountain View, California. What stands out in your mind about that experience?

It was the first place in which racial construction was a source of fascination and confusion for me. Growing up in the Philippines, America was all about Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson and Macaulay Culkin. So where do I, a Filipino, fit in to that black or white construction? It was confusing. I knew one Jewish family at [school], and I asked my friend if Jewish people were white. Most of the new immigrants these past few years are Latino and Asian. Where do they fit into that black and white binary?

You are often mistaken for being Latino because of your name, and you write that Latinos and Asians are left out of the black and white binary. Given that context, you asked yourself some dominant questions in the book: “Where do I go? Do I go black? Do I go white? Can I do both?” Do you have any answers?

This is one of the reasons these past few years have been difficult. I’ve been boxing myself in and being boxed into a progressive movement space. I was a reporter; I wasn’t supposed to be part of the movement. I was supposed to write about it as a journalist. I look Asian, my name is Latino and I’m a proud Filipino. I grew up in an environment where Jewish people were part of my life, black people had a huge influence on me and white people were family to me. I embrace all of those groups, and so when we go to a space where we talk about intersectionality, how we resist and being woke in this era, I find people stay in their corners, and I’m baffled by that. My experience has been so intersectional. I swallowed this country, and in doing so I was able to absorb a lot of cultures and a lot of people.

You’re one of the founders of a non-profit, Define American. Tell us about that.

Define American reflects my gratitude to this country. I came out as undocumented seven years ago. My story is very specific, and I knew the moment I came out and said I was undocumented people were going to project this model minority thing on me. I was acceptable because I was college educated, and I speak English. But I knew I couldn’t be the only story out there, and we started an organization that is founded on the power of storytelling. Story by story—one complex story to another—we take people out of this box they have been locked in due to their immigration status.

A big part of our work is also consulting for television shows or movies where there is an immigrant character or an immigration storyline. Thus far, we’ve consulted on 42 projects. This is a page we took from the LGBT movement, which gave us the gay-straight alliance movement. Therefore, we have this entire program within our work that is about integrating accurate humane storylines of immigrants. After all, the television shows people watch are a greater indicator of the way people vote than the political party they belong to. Putting an immigration story on a show like “Grey’s Anatomy” reaches more people than all the news channels together.

How does your experience as a journalist come into play at Define American?

As a journalist, I want to help news organizations better cover this issue. With some exceptions, I would argue that news organization do not know the depths of dehumanization immigrants have been going through since the Clinton era. Clinton passed some of the strictest immigration laws in the country. If I leave this country, I will face a 10-year bar from coming back, and there is no guarantee I could return. Most of the 11 million undocumented people have no path for legalization because of what happened in the ‘90s. Then 9/11 changed everything. The Immigration and Naturalization Service became Homeland Security, which houses ICE. We originally had an immigration bureaucracy structured to welcome and naturalize people that is now an agency terrorizing people. It wasn’t until Trump was elected that the American public and journalists realized ICE is the most rogue government enforcement agency. But that didn’t happen overnight. ICE grew under Bush, and it grew under Obama. With the book, I needed to make this situation personal.

This interview has been edited and condensed.