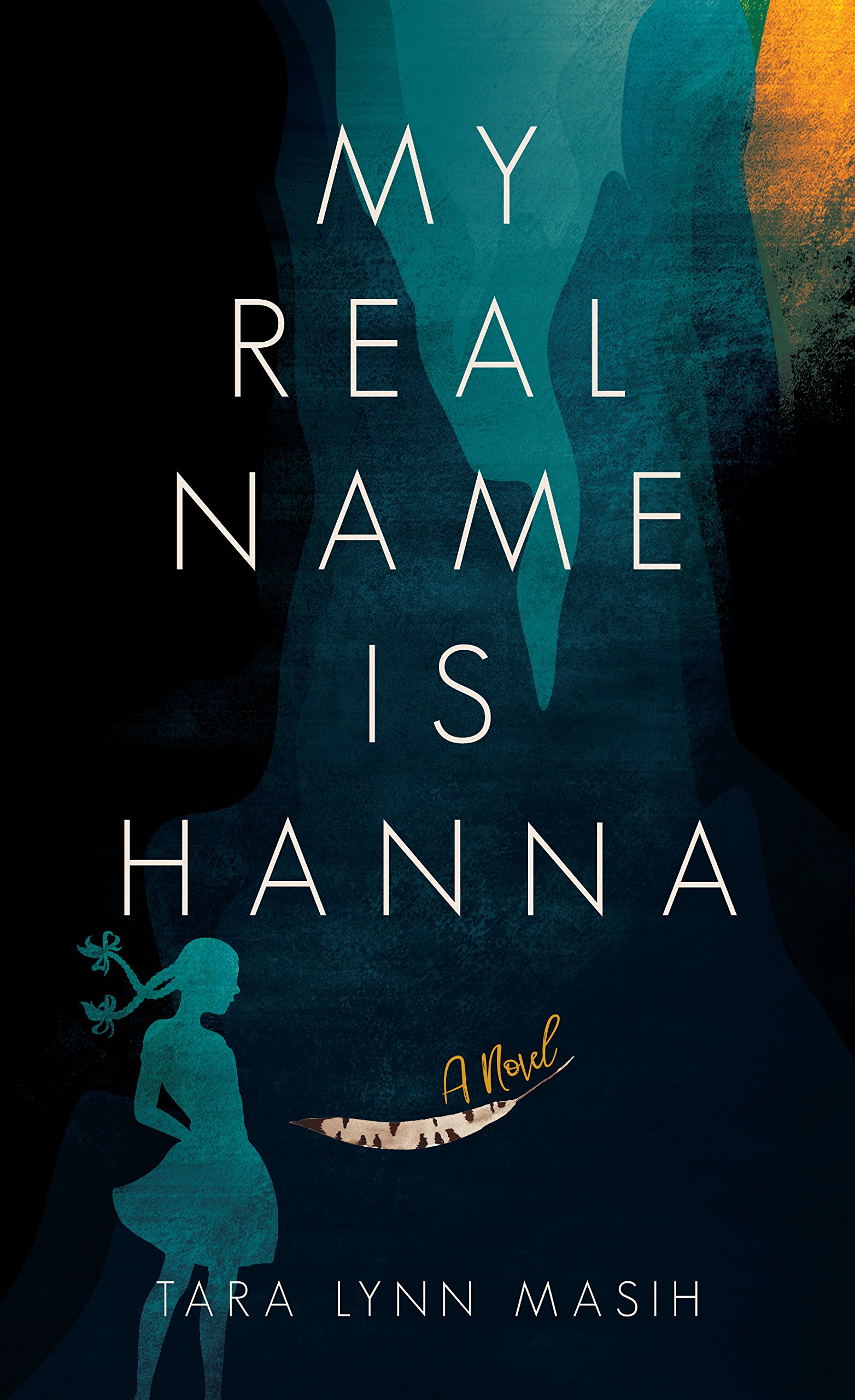

Tara Lynn Masih says the climate in America was different when she began writing her acclaimed young adult novel, “My Real Name is Hanna.” She noted it was “a relatively peaceful time for the country. Now anti-Semitism is on the rise. I didn’t know that when I finished the book, it would be as timely as it has become. People need to revisit the lessons of the Holocaust in this day and age.”

Fourteen-year-old Hanna Slivka and her family are at the center of Masih’s book. The family lives a relatively happy life in a Ukrainian village under Russian control. Hanna is close to her Christian neighbor, with whom she decorates Easter eggs as she also observes the Jewish holidays with her family. Then the Germans show up in 1939.

When life for the Jews becomes untenable, the family goes into hiding in an abandoned cabin in the forest. Soon after, it’s no longer safe to remain in the cabin, and a kind forester leads the family to a series of caves with underground lakes. It’s no easy task to survive under such extreme conditions, but Hanna and her family are determined to live.

Masih’s story is based on a real account of the Stermer family’s survival during World War II. Masih doesn’t so much embellish their story as she breathes life into it. Hanna is a compelling narrator whose observations place the reader in the cave with its hapless occupants.

Masih also masterfully conveys Hanna’s inner thoughts. The war, and even the Nazis, cannot suppress the sturdy Hanna’s optimism. Her complexity lies in the fact that although she is afraid much of the time, she is determined to find joy in her situation. Like many girls her age, she has a sweet love interest, conveying the life force within her. Although the reader knows from the beginning of the book that Hanna and her family will survive, Masih artfully builds tension.

She recently spoke to JewishBoston about her award-winning book—awards that include the Julia Ward Howe Award for Young Readers and the Foreword INDIES Book of the Year Award in Historical Fiction—and its place in Holocaust literature.

What drew you to the Stermer family’s story?

I’m very interested in the natural world, and I watched a documentary called “No Place on Earth.” The film featured the Stermer family, who hid in a cave during World War II. My family and I were deeply affected by the story. Any Holocaust story is incredibly powerful, but this drew me in because I knew it would appeal to younger people. I wrote the book before Trump’s election. As it turns out, young people today need more coping skills now given climate change, gun violence and an increase in bullying.

I’m also a bicultural person—my father is from India, and my mother is Eastern European. I grew up aware of different cultures. Teaching tolerance is in the background of all my writing. I want to do whatever I can in my creative endeavors to teach tolerance.

Why did you choose to fictionalize this story?

Although Esther Stermer wrote a memoir that is not readily available, I didn’t want to invade their story. Their grandchildren might want to retell it. My goal was to create a fictional family based on their survivor story. I changed some of the details. For example, I placed my family in the forest before they ended up in the caves. Although I created a fictional town, the story is set in the same general geography of the Stermer family house.

What attracted you to write about this particular Holocaust story?

This was a different Holocaust survival story. The family’s faith, culture and tradition helped them cling together during their 300-plus days in the caves. The question of survival is at its upmost during wartime. Who better to learn about survival than from Holocaust survivors? I was lucky to meet and talk with survivors. I consulted with a child survivor of the Holocaust to help with the details in the book. He grew up in a similar area. He read an early version of the book and redirected me about history and geography.

I’m in awe of Holocaust survivors. Especially those who maintained their ability to love other people and continue to function in the real world. Reading the book has allowed some survivors, especially those from Ukraine, to tell their stories for the first time.

You write movingly about righteous people who were not Jewish who helped in the Holocaust.

I wanted to portray the people who continued to help Jews despite the odds. Their families or their entire villages could have been killed in retaliation. It puts so much weight on that one potato that was passed on, or those interactions that provided shelter. The character of the Polish forester is based on the real story. The actual forester led the Stermer family to the caves in which they hid and told them when they could go out to find food. Outside the cave, the family was reliant on the area farmers. They would not have survived without them. These people risked their lives to trade with the Jews and gave them supplies. It was important to me to show how critical it is to have upstanders. It’s essential for young people to see how upstanding saves lives. I hope the young people who read my book will relate it to current events, such as bullying using social media.

There’s a large body of Holocaust literature. What distinguishes your book?

I know there’s a lot of Holocaust literature, but ask Holocaust survivors if there are too many Holocaust books out there. My intent in writing this book was not commercial; it was social. I heavily research the book, and it was approved by Holocaust survivors. It’s also a different story. Everyone should understand this period and see the depravity that existed. Yet there is also the hope from that time. This is an incredible story of how people can survive, especially underground. The women and children who were in those caves hold the record for surviving underground for 344 days. Think of that in relation to the Thai soccer team, some of whom were trapped in a cave for nine days [in 2018] or the Chilean miners who were trapped [in 2010] for 69 days.