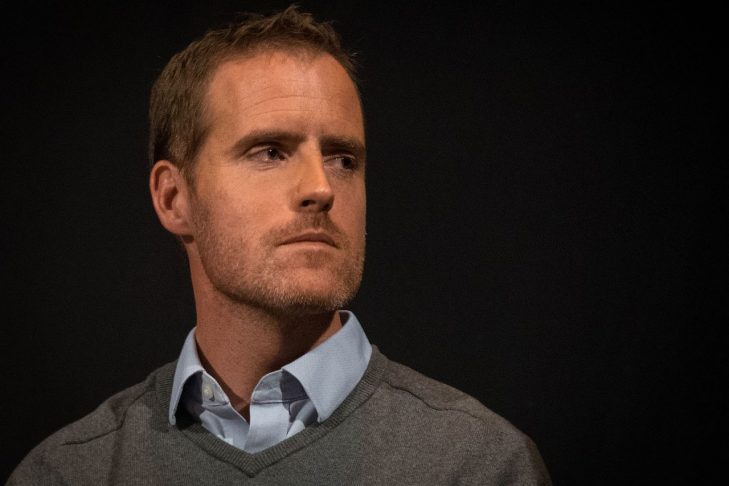

“When someone offers to introduce you to an old spy, you go,” Matti Friedman recently told JewishBoston. Friedman was referring to 90-year-old Isaac Shoshan, an original member of the “Arab Section,” a precursor to the Mossad, Israel’s intelligence arm. Shoshan is one of the four spies on whom Friedman focuses in his new book, “Spies of No Country: Secret Lives at the Birth of Israel.” In anticipation of writing his book, Friedman conducted extensive interviews with the nonagenarian in his apartment in suburban Tel Aviv.

Friedman, who has worked for The Associated Press as a foreign correspondent, has reported from Israel, Lebanon, Morocco and the former Soviet Union. He was born in Toronto and has lived in Jerusalem for many years. His first book, 2012’s “The Aleppo Codex: A True Story of Obsession, Faith, and the Pursuit of an Ancient Bible,” told the story of an ancient Bible manuscript that ended up in a cave in Aleppo, Syria. The book won the 2014 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature from the Jewish Book Council. His second book, 2016’s “Pumpkinflowers: A Soldier’s Story,” chronicled his time as an Israel Defense Forces soldier holding down an isolated outpost in southern Lebanon. The New York Times designated the memoir as a notable book. And “Spies of No Country” has recently been honored with the Natan Book Award.

Related

An important through line of “Spies of No Country” is a critical examination of identity, Jewish and otherwise. In the book, Friedman writes that these fledgling spies “were native to the Arab world, as native as Arabs. If the key to belonging to the Arabic nation was the Arabic language, as the Arab nationalists claimed, they were inside. So were they really pretending to be Arabs, or were they pretending to be people who weren’t Arabs pretending to be Arabs?”

“These young men were close to the Arab world in language and culture,” Friedman said. “Who they are is complicated, and I don’t answer that question in the book. Some call themselves Arab Jews and some don’t like the term. It’s definitely fuzzy and the Arab section sat on that fuzziness. That was the weapon. These guys were so similar to Arabs and passed for years. That’s what they did, and it has a lot do with the success of Israeli intelligence.”

In the 20 months before statehood, the four young men were deployed in Beirut and the Arab neighborhoods of Haifa. In Lebanon, the men ran a small concession stand selling snacks and school supplies near a school. In Haifa, two of them pulled off a daring car bombing in an Arab-owned garage. Friedman writes that, in general, their missions “didn’t culminate in a dramatic explosion that averted disaster, or in the solution of a devious puzzle. Their importance to history lies instead in what they turned out to be—the embryo of one of the world’s most formidable intelligence services.”

In addition to uncovering the roots of Israel’s highly successful spy program, Friedman also aims to supplement the Ashkenazi-European narrative regarding the founding of Israel. “I’m suggesting a different way to understand what happened in 1948 and what has happened since,” he said. “Many of us grew up with simple stories about Israel—stories about Herzl, the kibbutz movement, Zionism and the Holocaust. But half of the Jews in Israel initially came from the Arab world. They ended up shaping the state in many ways, but they’re still on the margins of the story we tell.”

Friedman asserted that key to understanding Israel is an acknowledgment of the country as thoroughly Middle Eastern rather than a European transplant of the Jewish world of Europe. “We need a creation story about that country that helps us understand the country we have in 2019,” he said. “Our politics, pop music, cuisine and behavior are Middle Eastern. Fifty percent of Israeli Jews have roots in the Islamic world.”

Friedman observed that political and societal fault lines separate Jews from the Middle East and Jews from Europe. In the early years of the Jewish state, the European idea of Zionism prevailed. Jews from the Middle East clashed with the kibbutz movement and the inherent socialism of those times. These difficulties lead to the question: What does the legacy of Friedman’s spy story mean for Mizrahi Jews and for European Jews?

“The existence of the state of Israel,” said Friedman, “is not the result of European crimes, but has to do with the way Jews of the Middle East were mistreated. We do ourselves a disservice when we marginalize that part of our story.”