My dad loves sports. He grew up in Chelsea, and even though he hasn’t lived remotely near Boston for several decades, he still follows the Red Sox with meticulous precision. When the Sox headed to the World Series in 2004, he spent most of the week pacing through the house and occasionally watching anxious 30-second snippets of the games. In school, he played baseball, basketball, football and rugby (or “scary football”). At one point, he was unanimously elected treasurer of his rugby team. His teammates’ reasoning? He was Jewish.

The stereotypes of Jewish men morph as the years do, but the core perceptions remain essentially the same. While Jewish women are shrieking harpies, Jewish men are demure, desexualized, devious. They are two devilish steps ahead of the golden boys, heads bowed over textbooks. While Brayden scores the winning touchdown, Joseph studies to become a doctor and outlives his entire graduating class. Of course, stereotypes rarely ring true in the way oppressors fling them. My Jewish friends come from expansive, eclectic backgrounds. They play music, they pursue a thousand different career paths, they skirt and shrug off assumptions like cobwebs. My dad may have an MBA, but he also has about half a functional shoulder from pitching. Nothing is ever as simple as we’d like it to be.

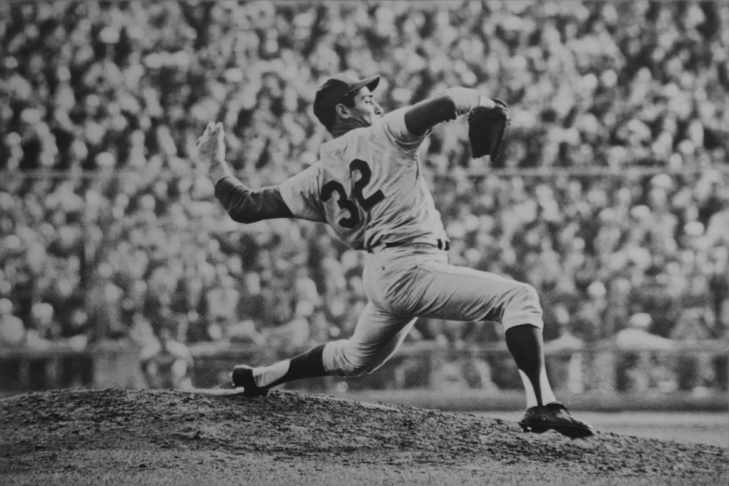

Baseball in particular is full of exceptional Jews, as my dad is quick to remind me. For example, Moe Berg, who debuted with the Brooklyn Robins in 1923 and went on to spy for the Office of Strategic Services during World War II. He spoke several languages and attended Princeton and Columbia, skirting the line between sports and studying as so many Jewish men do. Another player, Sandy Koufax, is considered one of the greatest left-handed pitchers in baseball history. He used his significant signing bonus to pay for the rest of his University of Cincinnati education, on the off chance his baseball career didn’t pan out.

Hyper-competency is a trait valued in many Jewish families, but this can become a double-edged sword. When a community lives with trauma and inescapable prejudice, excellence becomes the expectation, not the exception. The parental desire for a better life for their children takes on a new dimension when that better life could be torn away like a gossamer veil.

The ideally “masculine” Jewish man is educated, calculated, successful. The masculine American man finds no value in this. He is physically intimidating, blunt, alternately emotionally bereft and explosive. Sensitivity and contemplation are for women, and we all know there is no greater crime than resembling a woman. Perhaps this is why the stereotypes of Jewish men skew toward softness and weakness. Perhaps this is why my father became the treasurer of the rugby team. Traditionally American and Jewish conceptions of what makes a good man differ radically, which makes living as an American Jew difficult. It isn’t enough to get a college education or to pitch a fastball that can break a catcher’s wrist. An American Jewish man has to do both, perfectly.

It’s worth examining how these expectations affect Jewish men, how the cognitive dissonance creates people who have no idea what would make them happy or what they actually want. Ideal masculinity, like ideal femininity, is an unattainable goal. Striving toward perfection can only end in disappointment, particularly if a system is biased against a minority group. Expecting Jewish men to fulfill every aspect of masculinity is unrealistic. Claiming they fulfill stereotypes when they value education is reductive. The issue is nuanced and requires further examining, but allowing Jewish men to determine their own perceptions of what it means to be a man is a good first step.