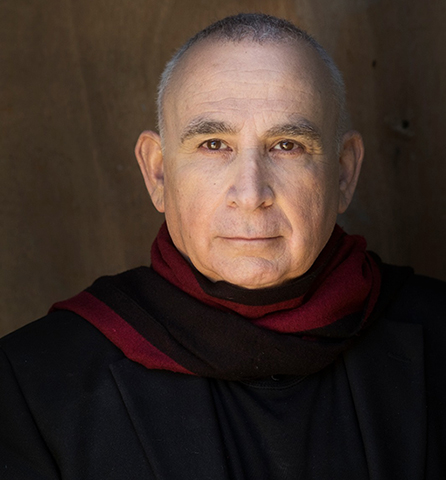

At his very core, Eliezer Armon, one of Israel’s most prominent and busiest architects, is a philosopher. Over the years he has honed a philosophy that mixes Kabbalah, martial arts and his experiences as a lieutenant colonel in the Israel Defense Forces and is fully reflected in the buildings he designs. He is also behind one of Israel’s largest housing booms, which aims to build 120,000 apartments across 27 Israeli cities with 35 transportation centers in the next decade. The numbers are as impressive as the man behind them.

The 63-year-old Armon was recently in Boston promoting his new book, “If Architecture is a Language, Then a Building is a Story.” The coffee-table book introduces readers to 15 of Armon’s spectacular buildings in full color that he pairs with short poetic prose fragments. Many of the buildings are in Israel’s Negev. “I was born in North Tel Aviv,” Armon told JewishBoston, “but like Abraham I decided to go to the desert.”

Armon lives and practices his craft in Beersheba, where he is continuously inspired by the desert and influenced by biblical stories. That influence comes together in the design of one of his buildings that he calls “Abraham’s Well” in Beersheba. Armon is an ebullient man who noted that he shares a name with Abraham’s servant, Eliezer. “Eliezer was Abraham’s chief operating officer,” he said. “He was so important to Abraham that he was given the task of finding Isaac a wife.”

Armon’s design integrates the shape of a tent and includes an actual well in the building’s yard. “Abraham lived in a tent as a nomad and God told him l’ech l’cha,” he said. “In essence this means God said, ‘Go and I will follow you.’ In the Visitors Center we follow Abraham and see that his mission was to go forth on his own power. The materials in the building reflect a sense of place.”

In his book, Armon contemplates the difference between space and place. He writes: “A building can successfully provide a physical function such as a shelter from rain and wind. However, success in this dimension, important as it is, could still be far from creating a place.” In verse he further explains: “Every structure I design/Has one central space/Which contains the entire story/It is there where I assemble the entire power/Like a martial artist/Who assembles and focuses/All the strengths of his body to a single spot.”

For Armon, incorporating spirituality into his designs is key to the transformation from space to place. That important change is evident in his emblematic design for the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. Facing the Knesset on one side and the Shrine of the Book on the other, the building is one of Armon’s masterpieces. It brings together many of the iconic elements of his design process. “The National Library best reflects my philosophy,” Armon said. “And Kabbalistic notions are also reflected in the design of that building. As I write in the book: ‘Letters for poetry/Are like bricks for a building/Both build stanzas and houses/One for the book/The other for the town/And thus I choose to plan my buildings/As stories/They stand in the public library/While the streets serve as shelves.’”

Armon pointed out that just as Hebrew letters have alternative meanings, his buildings are laden with Jewish allusions. In a synagogue he designed for the IDF Officers’ School in Mitzpe Ramon, Armon found significance in the story of the Burning Bush. “Moses gets his orders from the Burning Bush, and the story serves as the background for these officers’ missions,” he said.

To invoke the biblical episode, Armon enveloped the building in “concrete flames.” He added that “architects work in the shadow of God and are entrusted to continue and conjure the spirit within matter. Exposed concrete can also become a flame.” Armon’s interior synagogue design includes what he calls “a flying menorah on the ceiling. I also paid special attention to the table where we place the Torah.”

Armon’s creation for Yad Sarah in Beersheba, an Israeli institution that supports people after hospital stays and other life challenges, comes with its own intentions. “I tried to create an optimistic building for people with no hope,” he said. “That is the organization’s purpose.” Armon explained that the pyramid built into the front of the building is purposely cracked. “Yad Sarah supports people who have had a crack in their lives,” he added. “But a crack also lets in the light.”

Armon raises architecture to an art form that integrates his personal treatise on life. “I’m always looking for seeds, whether it is in the Kabbalah, my martial arts practice or my vocation as an architect, which bloomed in the desert,” he said. “I’m a proud Jew who fought in five wars for Israel. In Israel we have a wonderful language, wonderful people and a wonderful country. They are my inspiration. That is why my buildings are stories.”