It was impossible to not be emotional last Friday as I bounded down Rue La Fayette from my Gare du Nord area hotel toward Rue di Rivoli, where I would board a Paris CityVision bus to the beaches of Normandy.

Today, the 75th anniversary of D-Day in Normandy will be commemorated at Utah Beach and in Sainte Marie du Mont, where the first American paratroopers were dropped offshore right into bloody battle. Events will continue throughout the summer.

As I passed proprietors washing down the sidewalks of cafes in the early morning sun, I thought of the World War II veterans I had come to know while gathering the stories of Holocaust survivors and WWII liberating soldiers. All humbly conveyed their grueling experiences with the authenticity that can only come from first-hand witnesses.

It was my 19th trip to Europe, and time to see Omaha Beach for myself.

According to the National World War II Museum, the D in D-Day simply means “day,” to denote major military operations.

But D-Day 1944, or its code name Operation Overlord, holds special significance for its dramatic role in breaking the Nazi stronghold in France and paving the way to the Allied victory.

As we passed the Place de la Concorde, made our way through the Avenue des Champs-Élysées and around the free-for-all rotary behind the Arc de Triomphe on our way out of Paris, our tour guide explained that “Normandy” is a derivative of “North Man Land,” named for Vikings who had come from the north 10 centuries ago.

Following the Norman Invasion of 1066, William the Conqueror, the first Norman King of England, adjoined Normandy and England. It went back and forth, England reclaiming the land during the Hundred Years’ War, and became permanently French only in 1450, following the Battle of Formigny.

Today, the region has 3 million inhabitants who are mostly farmers. “It has also seduced many painters and artists,” our guide told us.

We could see why. Our itinerary stressed the beautiful landscapes of the Normandy countryside, and indeed, they were bucolic and green, with lovely European stone homes, grazing livestock and tidy agricultural fields. All provided a soothing juxtaposition to the somber history we would soon experience.

Our seven-hour immersion began in the city of Caen, which was liberated by Canadian troops and now has 200,000 inhabitants, and the Caen Memorial Museum. There, amid military vehicles and equipment, we toured exhibits and viewed films that detailed the stages of WWII, with a focus on the lengthy Battle of Normandy.

Following a delectable Norman lunch in the restaurant that included kir, sauteed veal and olives, a carrot slaw, vegetable and meat salad, Norman rice pudding and regional apple treats, we rode past fields of flax, canola, wheat and apple trees, as well as trees dotted with clumps of mistletoe en route to our first visit to a landing site, the Pointe du Hoc, with its steep cliffs that overlook Utah and Omaha beaches.

Our guide told us that all the beaches were spontaneously named. For example, Omaha and Utah were simply the homes of two American carpenters working for D-Day ground troops commander Gen. Omar Bradley.

Along the roads leading to Omaha Beach, we passed the fields where the paratroopers first landed, and a museum surrounded by German military artifacts. We disembarked by a display that chronicled several soldiers killed just after landing, and walked down the path of a former battlefield.

It took about 10 minutes to reach the edge of a cliff, and we proceeded into the former minefield amid eerie bomb craters and German bunkers that served as lookouts for rapid machine-gunning. These were bomb-proof, many were connected and always-chilling barbed wire remained.

I paused at a memorial to the American Rangers Battalions built atop a former German commanding post.

The United States Army Rangers are graduates of combat leadership training at the U.S. Army Ranger School. On D-Day, Lieutenant Colonel James E. Rudder and his 225 soldiers from the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions scaled these cliffs to surprise and vanquish enemy positions.

Although the Germans had indeed not considered that U.S. military would deem the clifftop accessible by sea, according to the display we had passed, losses were heavy. Only 90 were able to bear arms when relief forces arrived on June 8. And during this and the Omaha Beach battles, of the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions, 96 were killed, 183 were wounded and 32 went missing.

“We were a bunch of kids who were scared to death,” recalls D-Day veteran Jacob Katz of Boston, who changed his name to Kates after the war. “We landed fighting and shooting and trying to stay alive. Bodies were falling everywhere and we just moved as fast as we could.”

Kates, who will turn 100 this August, was in the 4th Infantry, Battery B, 20th Field Artillary Battalion. “They knew it would be risky and dangerous, but had no idea what was waiting for them,” said his daughter, Leslie Kates Wortzman of Framingham.

“They lived on the amphibian units for two weeks,” she added. “They lay in hammocks, one stacked on top of another, getting sick over the side all the time.”

But they gave their best. “We kept on fighting and marching, fighting and marching, never really knowing where we were and which hedgerow the Germans were going to be over. That was the scariest part,” said Kates, who went on to battle all through northern France, the Rhineland, where he was in the Battle of the Bulge, Ardennes and Central Europe.

Kates’ battalion was activated in June 1940 at Fort Benning in Georgia as part of the 4th Division, to be later named the 4th Infantry Division. Battery B fought in five WWII campaigns and was inactivated in 1946 at Camp Butner, North Carolina.

I asked Wortzman if her dad remembered when things went awry, when the Allies miscalculated where their missiles would land and where the paratroopers would drop.

“No, this is not something he was aware of, but he did talk about friendly fire being an additional danger, since everyone was fighting for their lives in the open,” she said. “It was too chaotic already for them to focus on that.”

As stated in a Caen Museum display, of the total 350,000 Allied troops who took part in D-Day, including the 156,000 troops who landed on the Normandy beaches, about 9,000 were casualties on that first day. By the end of the Battle of Normandy, the Allies suffered over 200,000 casualties, including more than 50,000 who were killed.

While I have written extensively from the perspective of surviving prisoners and soldiers, it was a stark encounter with the reality of massive deaths of the soldiers trying to wrest Europe, and my people, from Nazi control. And with tearful pride and sorrow, I was now there.

As our guide told us and the Caen exhibits detailed, the landings of June 6, 1944, were the largest military operation in history, and ultimately opened a new European front against Nazi troops. Over 150,000 soldiers from America, Britain, Canada and many other Allied nations landed by sea and air on Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword beaches and the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc.

It was the beginning of the end for the enemy. “Hitler had asked his men to fight until the end, but they knew it was already the end,” our guide said.

Still, as we learned at the Caen Memorial Museum, the Battle of Normandy was not easily won. From the first landing, facing the ocean were 5 million German mines, positioned there to stop the ships from arriving.

Our guide explained that the Germans expected the attacks to take place perhaps at Dunkirk, where the British and French evacuated north of France, or from Dover to Calais, the shortest way to get to France. In fact, he said, Patton’s troops were over there, with a ghost Army employing rubber planes and decoy weaponry.

But Normandy was the German Army’s weakest point, and the surprise attacks were planned for early in the month, when the full moon and the highest tides would help camouflage the sea arrivals. Eisenhower had to delay the landing by a day due to a storm, and as I know from the soldiers I have interviewed, the weather was typically bad, the water was freezing cold and the seas were rough.

Thousands of landing crafts were boarded at night. As a display at Caen detailed, America struck first, at 6:30 a.m at Utah and Omaha, and were successively followed by British and Canadian troops down the coasts.

The initial bombings missed the German targets, giving the Germans time to reorganize. Their excellence in equipment and the Allied tactical errors ultimately prolonged the bloody conflict for 100 days until it finally ended with the Germans trapped, and the Sept. 12 liberation of Le Havre.

Eighty-five percent of Normandy had been bombed out, and it took 25 years to reconstruct the region.

Following Utah, we arrived at Omaha Beach, where I collected shells on its light sandy shore to place in the small D-Day commemorative jars I had purchased at Caen, and viewed its grand metal sculpture memorializing the Allied troops. The area was punctuated with flags of all the Allied nations, posters commemorating fallen heroes and a few restaurants and lodging establishments paying homage.

The Normandy American Cemetery in the town of Colleville-sur-Mer was next. At the Caen, I read that the remains of 9,387 Americans are buried there, and on the Walls of the Missing, 1,557 are remembered.

According to our itinerary, it is a 170-acre site, with white marble headstones aligned in rows across the lawns. It is just one of 25 permanent burial sites in the U.S. and abroad, but is situated right above Omaha Beach.

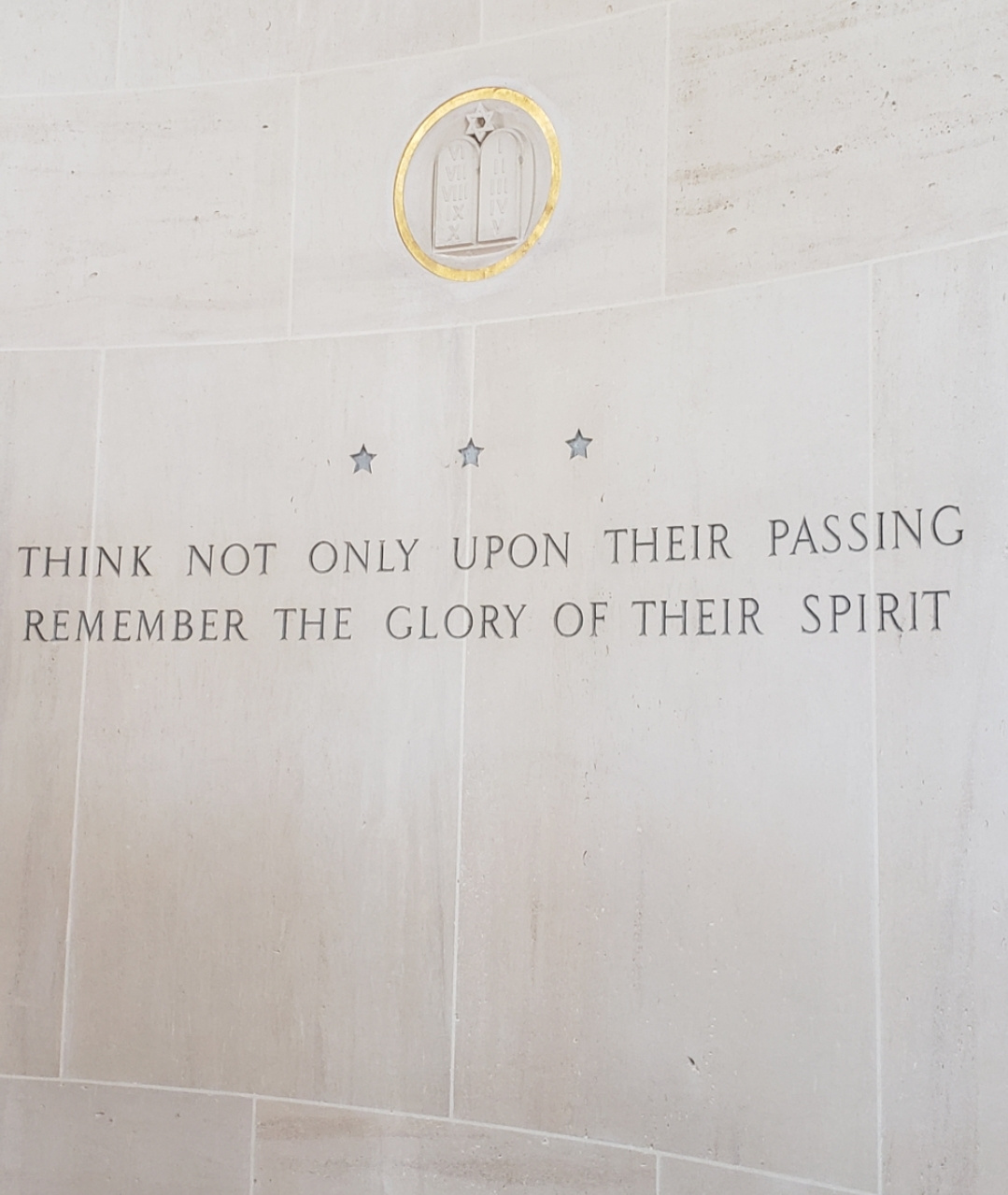

I was heartened to see Jewish stars among the crosses, and a plaque with a Jewish star and the Ten Commandments on the wall of the site’s chapel, as well as a similar Hebraic memorial on its dais.

Wortzman told me that each family “owns” a grave of an American soldier and cares for it. “They pass the grave down in their family and no one forgets,” she said.

Our guide told us that there were also Muslim soldiers among those buried at the cemetery. (“Back then, it was not an issue,” he said sadly.) I looked but could not find any headstones for them.

Nor did I locate the grave of Medal of Honor recipient Gen. Theodore Roosevelt, the eldest son of President Teddy Roosevelt, a WWI infantryman who remained in the reserves, led his men from Utah Beach on D-Day and then died of a heart attack in July 1944. The body of his younger brother Quentin, a pilot in the First World War who was killed in action, was exhumed from the WWI Oise-Aisne American Cemetery 244 miles east in northern France, and reinterred aside his brother.

The headstones of Preston and Robert Niland, the brothers who inspired the 1998 “Saving Private Ryan” film, are also there.

They are two pairs of a total of 33 pairs of brothers buried side by side at the cemetery.

Wortzman and her husband, Jerry, took Kates back in April 2008. “He had never talked about the war until our daughter, Ariel, started interviewing him for a project,” she said. “He said he had no idea where he had been, because they just kept marching and fighting and never stopping.” They asked Jacob if he would be interested in seeing where he was, and he said yes.

They also took him into Paris, because he had marched into the city to liberate it as well.

“We brought him to wherever he fought, to all the places where his battalion was celebrated with monuments, museums and street signs,” Wortzman said. “People stopped and asked if he was there. He would say ‘Yes,’ and they would shake his hand and say, ‘Thank you so much,'” she recalled.

“At the cemetery, he rode on the big artillery cannon and is amazed he never got killed on that,” said Wortzman.

“They had him stand to Taps, and take down the flag,” she said. “They had him speak to high school students who were there from around the world. Restaurants wanted pictures and autographs, and had him sign their walls and bars. He said it felt so special, like he had really done something important.”

He had. Kates received a Légion d’Honneur from the French government, a Good Conduct Medal, a European African Middle Eastern Theater Campaign Ribbon with Bronze Service Arrowhead and an American Defense Service Medal.

At the cemetery’s memorial plaza, our tour group gazed at the bronze statue “Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves.”

Apple trees dotted the roadways outside the cemetery, a sign of the ever renewal of life. We continued along into the Anglo-Canadian troop sectors. In the distance was Bayeux, a town that was not bombed and was the first French town to be liberated.

Next was Gold Beach, where British soldiers landed. “There were Russian soldiers in the German ranks there, but many refused to fight, and that helped,” said our guide.

The historic town is known for its fabricated port, which was built in two weeks to aid the Normandy landings and is still known as “Port Winston.”

On D-Day, nearly 10,000 tons of equipment was unloaded there, including reinforced concrete “Phoenix” hollow structures that, as we saw from the bus, still float there today.

Weighing 5,000-7,000 tons each, they were tugged by boat from England. Filled with compressed air, they floated until deflated for use on the shore. The harbor was also filled with an artificial smoke screen to avoid detection.

Military relics appeared along our way, in front of small museums or alone with plaques, as we saw erected beside a Duplex Drive, or “DD” tank.

These were swimming amphibious Sherman Tanks with flotation screens (thus called “Donald Duck” tanks by American soldiers). Replicas today shuttle tourists around cities on “Duck Boat” tours. I’ve been on one in Boston, and now more fully grasped the significance of the vehicles.

On a hill, we saw the double Cross of Lorraine, the symbol of the French Resistance, perched on high as the bus turned into our final stop at Juno Beach, where on D-Day, 14,000 3rd Canadian Infantry Division troops landed. With machine-gun fire and hand-to-hand combat, they fiercely fought German strongholds, the most formidable after those of Omaha, on the land-line pocketed beach before advancing inland and securing a bridgehead that proved pivotal for the Allied invasion. Casualties were heavy, but at the end of June 6, these Canadian soldiers bore further into France than any other division.

As with the other beaches, carefully preserved military relics were outside, under Canadian and French flags. At the information center, I purchased souvenirs for a friend in Toronto who will now have reason to love his country even more than he already does.

Over the long ride back to Paris, the bus was quiet, with many of us surely caught up in what we had experienced. I thought I had learned a great deal from my previous work, but now, more than ever, I understood that without the Allied Forces’ collective, monumental bravery and too often ultimate sacrifice, life as we know it may very well not have existed.

“The people of the city of Caen and its surrounding area keep the memory of these events alive for veterans and their families,” our materials stated.

And following this trip, my sense of gratitude now extended to these residents who, with equal measures of pride and responsibility, uphold their historic legacy.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE