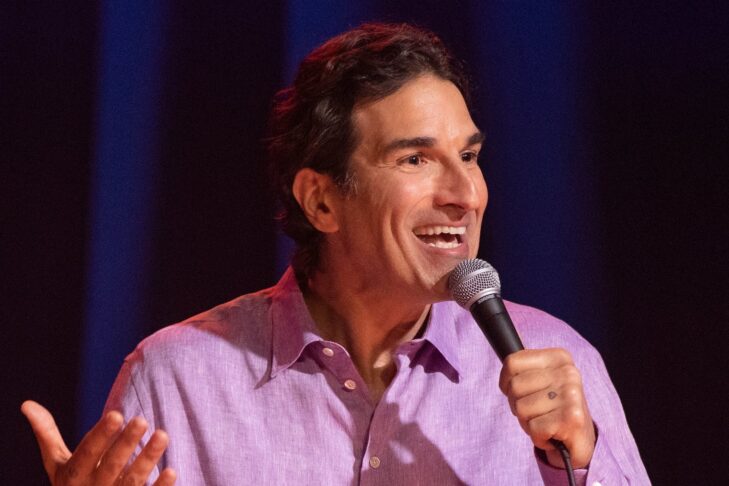

Jewish comic and Peabody native Gary Gulman begins his new HBO special “The Great Depresh” with a notice that is formatted like a content warning: “This program contains depression, and that’s OK.”

It’s more than OK. It’s a spectacular comeback for Gulman, who suffered from paralyzing depression in 2017 and has come back to relive it through pathos and comedy. Pairing comedy and mental illness is not new, but what Gulman does with that combination in 75 minutes is both fresh and crushing. His timing and delivery of his material create moments that seize the heart. You laugh, you cry. In fact, crying is the most surprising and joyful part of the experience. You cry because you know everything will eventually be all right.

Here’s Gulman’s riff about the side effects of anti-depressants. He smiles as he tells his audience that the only side effect of depression that concerns him is death. By the time he finishes conveying his hard-won wisdom, I was crying.

“They call it suicide, but I feel that word is incomplete. I think they should call it death from depression, not suicide. I’ll take any of the side effects [of medication]. … Diarrhea is so much more productive than depression. I can get out of bed with diarrhea. Impotence? Oh yeah, I was having so much sex in the fetal position. Yes, give me impotence. … I will take diarrhea and impotence simultaneously. If I can smile at a sunset, I will stand there in my soiled underwear and flaccidly grin ear-to-ear. Because when I’m in my right mind, a sunset is justification for existence.”

Gulman traces his depression to his 1970s childhood and connects footage from his life to his live stage performance. What he ends up giving us is a hybrid show, one that borders on documentary. We meet his mother, who still lives in Gulman’s childhood home in Peabody. An early scene in the special shows him and his mother, Barbara, looking at a book that Gulman wrote and illustrated as a child called, “The Loneliest Tree.” The eponymous tree is watered with tears. Yet Barbara remembers that Gary was always smiling. “A happier kid you couldn’t find,” she says. The line lingers. No doubt Barbara struggled to raise her sons as a single mother and may have been in denial. But it’s also telling of the great lengths Gulman went to hide his depression.

Gulman goes on to explore the link between stoicism and fallacies about masculinity. He recalls that Clint Eastwood was the role model for the ideal man. Eastwood, said Gulman, was strong and silent; “otherwise you were Richard Simmons.” In another joke, Gulman recalls how drinking Sprite versus Coca-Cola raised questions about a guy’s sexuality.

At 6 feet, 6 inches tall, Gulman was recruited to play football for Boston College. He struggled with his ongoing depression from the moment he arrived on campus. He describes how he stopped eating and lost 30 pounds in less than a month. He slept the moment football practice ended and didn’t wake up until it began the next day. He confided in a team trainer, who sent him to a therapist. “Thank heaven, this guy was sharp. … This was 1989. This was 10 years before ‘The Sopranos’ made it cool for big men to seek therapy.” Later in the show, Gulman observes, “Therapy, what a revelation—saved my life over and over again.”

Another piece of footage shows Gulman and fellow comic Bob Kelly talking openly about their struggles with depression and the fear that Kelly succinctly states as, “If I remove the depression, then I remove the funny.” Gulman confronts that myth in “The Great Depresh” by letting go of trying to be funny and simply telling his story. In an interview with New York Magazine’s Vulture section, he noted that on his whiteboard at home he wrote a note to himself to “commit to the truths as well as the jokes.” Gulman further explained, “I’m really great at committing to jokes and selling them, but I’m not a public speaker, I’m a comedian. So it was a different approach to commit to the parts that didn’t have a punch line at the end.”

As for his recovery, Gulman had the support of his wife, Sade, and an insightful psychiatrist. In one scene, we meet Dr. Friedman with Gulman and Sade as the three of them discuss Gulman’s recovery. Reflecting on that time in the Vulture interview, Gulman described his life as a “living death that was haunting [me] for two-and-a-half years. And then, suddenly and dramatically, my mood changed and I became alive again and I was able to write all this stuff and get it out there. It feels like a miracle, and I pinch myself a lot.”

Gulman unambiguously presents the deep, dark places where his depression existed. We go there with him because we know we will emerge wiser and more hopeful. And we trust him when he reassures us: “If you are suffering from a mental illness, I promise you are not alone.”