An interesting footnote of American history is the fact that one of the nation’s most enduring poems was written by a Jewish woman of Sephardic descent. Composed in 1883, the words of Emma Lazarus—traditionally a welcoming anthem for immigrants to America—are engraved on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free/The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.” Ken Cuccinelli, the Trump administration’s acting chief of immigration, however, recently revised the poem’s lines. In his version, Cuccinelli declared: “Give me your tired and your poor who can stand on their own two feet, and who will not be a public charge.”

Cuccinelli’s extemporaneous rewrite happened during a recent interview with NPR. The government official was defending a new rule that bars legal immigrants who are receiving benefits such as food stamps and Medicaid from becoming permanent residents.

Cuccinelli’s rephrasing of Lazarus’ stanza, which is part of her longer poem “The New Colossus,” prompted Annie Polland, executive director of the American Jewish Historical Society (AJHS) in New York, to refute Cuccinelli’s interpretation. In an interview with JewishBoston, Polland described Lazarus’s poem as “a beacon for all immigrants.”

The AJHS archives include Lazarus’s handwritten copy of the iconic poem. “AJHS houses all sorts of documents for Jewish organizations and important families and individuals,” Polland said. “The prime function and mission of many of those Jewish organizations was to help immigrants. It was part of the American Jewish experience.”

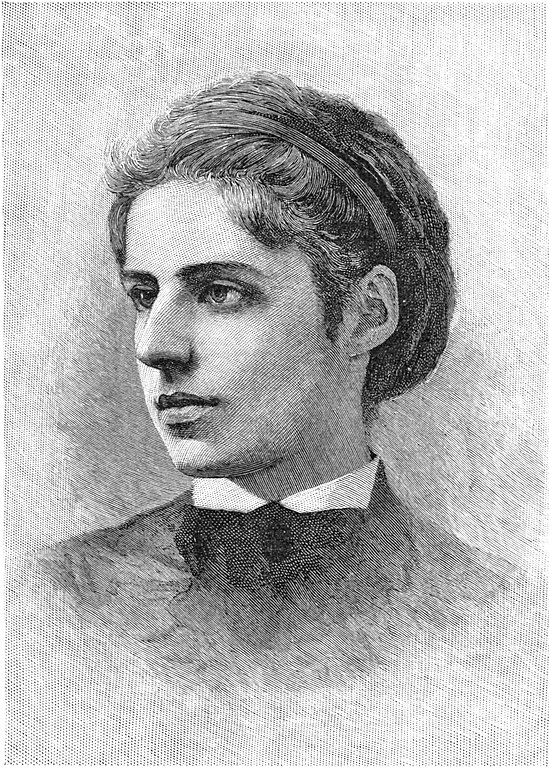

Lazarus was born in New York City in 1849 to a well-established Sephardic Jewish family. A fifth-generation American, she began publishing poems as a teenager and eventually became part of a circle of writers that included Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry James. Her extended family was among the early leaders at Congregation Shearith Israel—the Spanish Portuguese synagogue in New York—and the first Jewish congregation in the United States.

Although not a particularly observant Jew, Lazarus was an avid reader of Jewish history and integrated the subject into her work. Polland said “The New Colossus” was inspired in part by Lazarus’s charity work with large numbers of Eastern European Jews who arrived in New York in the 1880s. “Emma visited the temporary housing for Jewish refugees on Ward Island and was shocked at the horrible conditions,” Polland said. “She taught English there and wrote on their behalf. She wrote for a large American audience about the dangers of Russian anti-Semitism. In the Jewish press, she focused on the need to help Eastern European Jews. She said that Jews were not exempt from helping these people, even if they spoke a different language. It was Emma who articulated the famous sentiment, ‘Until we are all free, none of us is free.’ She was initially talking about Jews, but the phrase went on to apply to all people.”

According to Polland, Lazarus wrote the poem as part of a fundraising effort for the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal. Lazarus initially resisted writing the poem “on command.” But the friend who made the request, Constance Cary Harrison, persuaded Lazarus to write it in honor of the immigrants she was helping. “Constance Cary Harrison told Emma, ‘Think of all the immigrants who will see the Statue of Liberty as their boats come into the harbor,’” Polland said. “This appealed to Emma, and three days later she came back with ‘The New Colossus.’ The poem means a lot to Americans and to American Jews, who strongly identify with their immigrant ancestors. Immigration is what binds the Jewish community to this country. It’s what brought us here.”

Lazarus’s importance in American Jewish history has recently been highlighted in an eponymous three-year initiative of AJHS. The Emma Lazarus Project takes AJHS archival material associated with the Jewish American poet to create an exhibition that recreates the sitting room in her brownstone. There’s a blank folio on a table, on which Lazarus’ story is projected. There’s also a school curriculum in which students “can study the relationship between the Statue of Liberty and Emma’s poem,” said Polland. “Students learn about Emma Lazarus’ short life—she died in 1887 at the age of 38—and how she came to find her voice. We encourage students to write about the issues important to them and to write original poetry about the Statue of Liberty. We are sponsoring a national poetry contest along those lines.”

The Covenant Foundation has funded the AJHS curriculum. “The Covenant Foundation is primarily interested in Jewish education,” Polland said. “But they liked our project because it could also be used in public and secular schools. The idea that a Jewish woman wrote one of America’s most enduring poems, the words of which are on one of our most iconic symbols, is incredible.”