When Erin Khar was 8 years old, she popped her first pill—it was a painkiller that she found in her grandmother’s medicine cabinet. She recalled that the warning label said the medication would induce drowsiness. That was appealing to Khar, who was desperate to erase memories of an earlier trauma.

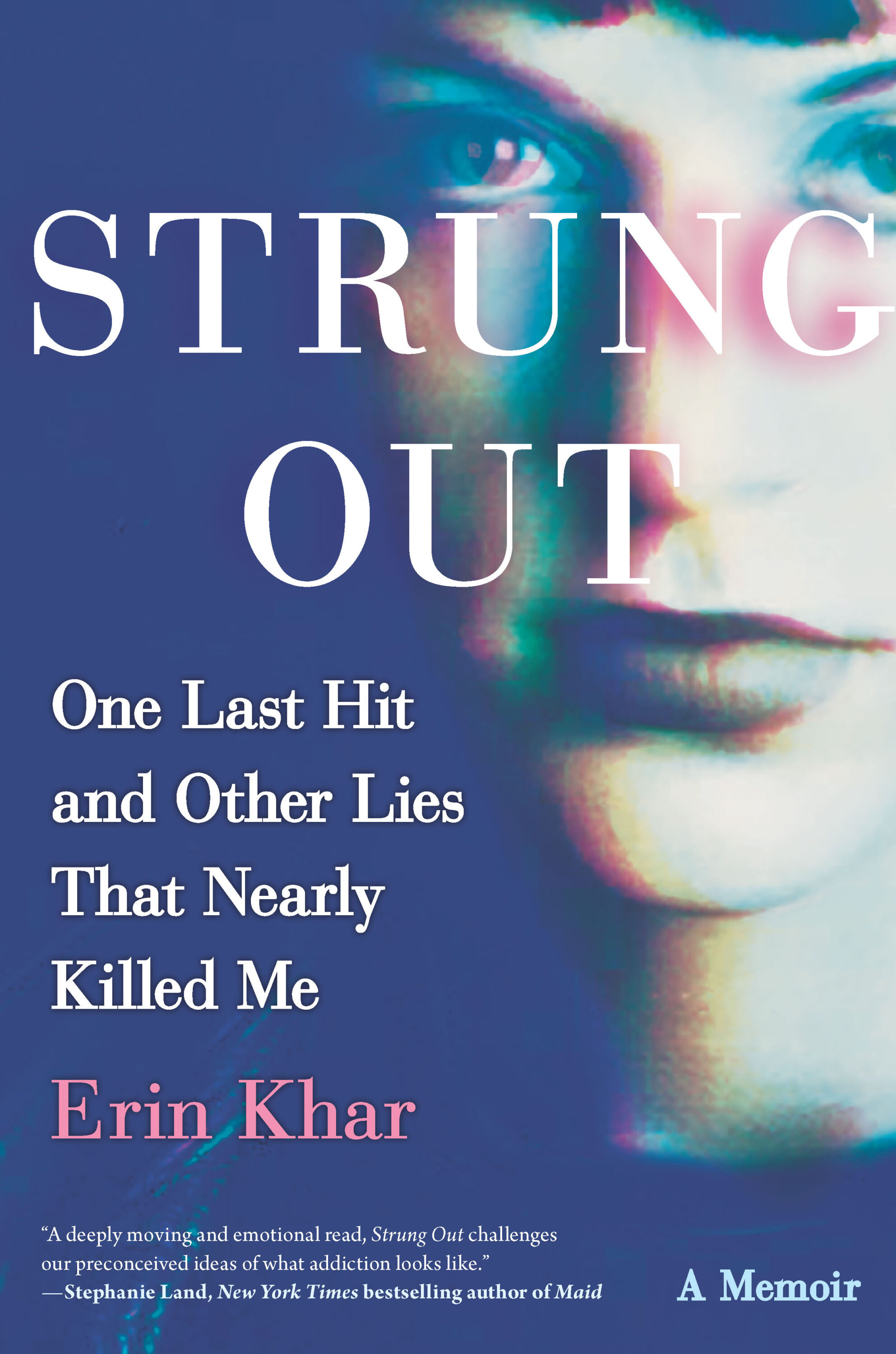

The only child of well-to-do parents who divorced when she was very young, Khar was 13 years old when an older boyfriend introduced her to heroin. For two decades, Khar struggled with an opioid addiction. She chronicles that time and beyond in her evocative and affecting new memoir, “Strung Out: One Last Hit and Other Lies That Nearly Killed Me.”

Now the mother of two sons, and a Jew by choice, Khar is an editor at Ravishly, where she writes the advice column “Ask Erin.” Khar spoke to JewishBoston about Judaism, addiction and her recovery.

At the beginning of your book, you considered yourself broken or even a monster. When did that begin to change for you?

A lot changed for me with the birth of my first son, Atticus. From that first moment of looking at him, I hadn’t anticipated the kind of love I would feel. That love was much stronger than the hatred I had for myself. That was the first turn in the right direction. It was the impetus for me to do all of this work through talk therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy and seeing a psychiatrist.

As I started to unpack everything, I realized this was a belief system that I had about myself that was created very early. For a long time, I knew on an intellectual level that that wasn’t true, but I couldn’t convince my emotional self to believe it. So it took some time to catch up, which is true for a lot of people. We have created belief systems about ourselves that aren’t true, even when we’re not struggling with something as big as addiction.

Your book makes a compelling case for decriminalizing drug addiction.

If you look at the psychology of addiction, there’s a huge component of it that is shame-based when somebody gets arrested for a felony drug possession. If they are somebody with financial means or somebody who has white privilege, chances are they will probably get diverted to drug court and go to rehab. If they’re a person of color and they don’t have the means to hire their own lawyer, etc., they have often ended up serving time and have a felony conviction on their record.

This adds shame upon shame. When you add shame to somebody who’s already walking around with an immense amount of it, you’re not doing anything to solve the problem. We know the way our judicial system is set up does nothing to rehabilitate people who are incarcerated. If we took the money we spent incarcerating and diverted it into programs to rehabilitate people and do early intervention programs, we would see a huge difference in the crime rate. We would also see a huge difference in the number of people who are incarcerated, and certainly a huge difference in the state of addiction.

There are almost 20 million people struggling with addiction right now. That’s not just opioids. Over 100 people die every day in this country from an opioid overdose. One of the most fundamental things we can understand and teach about addiction is that it starts long before the drug ever enters the picture. This is why I’m a fan of early intervention.

You came from a relatively privileged background.

Something I always talk about when I tell my story is that I came from a good amount of financial privilege. When I reached out for help, I had a family that was there to enable me financially to access care. Yet it still took me a long time to crawl my way out of addiction. You take somebody who does not have access to care, somebody who has financial barriers, racial barriers, socioeconomic barriers, cultural barriers to getting care, and it’s infinitely more difficult to get out of that cycle of addiction.

What has your journey to Judaism been like?

When my husband and I began getting serious, I knew it was important to him to raise his children Jewish. I didn’t really grow up with any strong religious affiliation. Atticus made the decision that he wanted to go to Hebrew school, so we found a synagogue here in New York where the rabbis said we didn’t have to convert to attend. There was never any pressure about it, which sets Judaism apart from some other faiths. There’s just no proselytizing, and that was really appealing to me. We were welcomed into a community that made us feel like we belonged there. I never felt like an outsider or different because I was converting.

What in particular about Judaism inspires you?

Being of service and healing the world. These are things that are really important to me, and so it all fell into place really effortlessly. I remember one defining moment: We’d gathered for a parent-student program at religious school and the rabbi was leading a discussion between the parents and students. He said, “If you believe in God, I want you to write down what God means to you. What word comes to your mind?” I thought I heard him incorrectly. I always had this idea that if you were going to affiliate with a religion, you had to believe in God. But he explained to me that it was just as important to be willing to struggle with the question.

You’ve been clean for 17 years. Do you ever worry about relapsing?

On some level, I know that’s always a possibility. But it’s been so long, and I haven’t had cravings in so many years. I also can’t quite connect to a good feeling of being high without the accompanying anxiety and shame. At the end, it didn’t even give me relief anymore. I’ve walked through some painful things without drugs that I never thought I’d be able to, and I never once thought, “Oh, that’s the solution.”

What do you hope people will take away from your book?

I want people to experience in this very intimate way what it’s like to be an addict and understand that it’s a human experience. There’s this othering of addiction; that’s very easy to do. It’s like feeling, “Oh, this could never happen to me,” but it can. It happens to every kind of person. Understanding that those underlying feelings are very universal makes it much easier to talk about and de-stigmatizes it, which is exactly what I want.