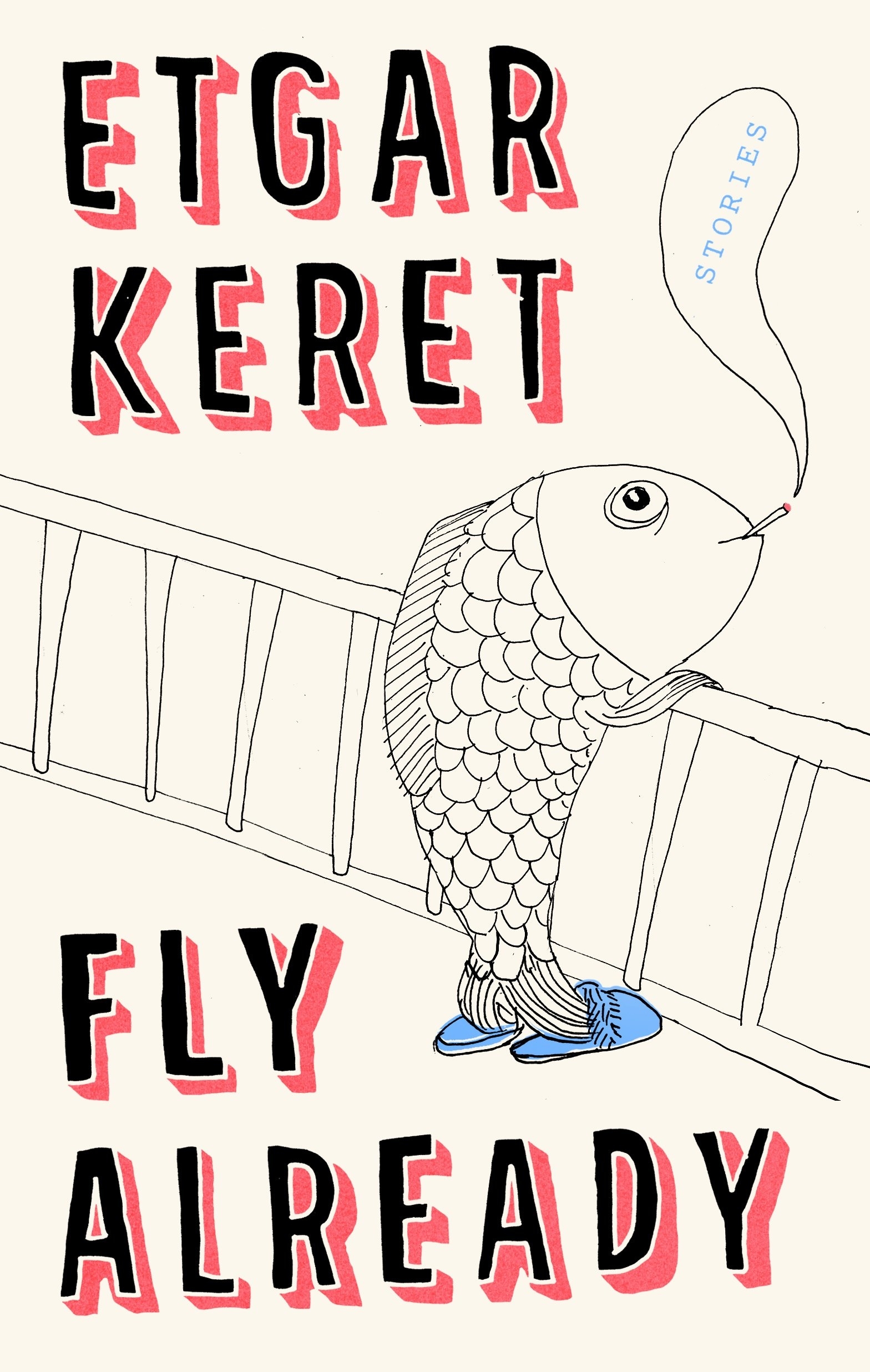

The organizing principle of Etgar Keret’s new short story collection, “Fly Already,” is one of near-tragedy. A few years ago, Keret was in a car accident in Connecticut while on a book tour. The resulting somberness is manifest in the 22 stories that comprise his latest volume of fiction. While Keret’s work has been called Kafkaesque and surrealistic, the 52-year-old Israeli author sees the surrealism in his stories as beside the point. In a recent wide-ranging conversation with JewishBoston, Keret noted: “The peak of one of my stories is not surrealistic at all. There is a universe, and if the laws of physics are broken in my stories, it’s not to create a peak in it. The surrealism is a natural part of the architecture of the work. It is part of the background.”

Over the years, Keret has been regarded as a literary trickster whose work didn’t have as much gravitas as that of his writing elders Amos Oz, David Grossman or A.B. Yehoshua. Those writers took on archetypal themes of war and peace and Arab and Israel co-existence. While Keret worries about his country and sees “a scenario in which we could destroy ourselves,” strictly speaking his work is not political. His oeuvre is not particularly Israeli in theme either, although he writes in his native Hebrew.

Keret said when he began writing during his army service, he read Kafka and Vonnegut. “Reading ‘Slaughterhouse-Five’ in the army was the best time to do that,” he said. “The book made perfect sense to me. It was both horrible and humorous at the same time—an autobiography and science fiction book. This activity of moving through genres without preaching was like a Big Bang for me.”

Keret’s work has been translated into more than 40 languages. Until recently, he remained under the radar, making him a cult favorite among millennials. “Many of my readers are students and compulsory army soldiers,” he said. Keret joked that his books have the distinction of being the most shoplifted in Israel. “My readers are people who can’t afford to buy my books,” he said. “I once got fan mail from a reader who wrote that she had shoplifted all of my books, but she had to wait until the winter when she could wear a big coat to steal the graphic novel I published.”

This past year, Israel’s literary establishment finally welcomed Keret with the Sapir Prize, the country’s most prestigious literary award. The praise that came with the prize asserted that Keret’s characters “are connected to each other through alienation, loneliness, and a strong feeling of abandonment in the world.” Keret noted that his characters are often orphans or people who are isolated. In the title story, “Fly Already,” a widower and his young son notice a man who is about to jump off the roof of an apartment building. The boy thinks the man is a superhero who can fly, while the father—a survivor of a recent car accident that killed his wife—recognizes that the man is about to kill himself. A woman with red hair sees the father and son duo on the roof and thinks they are the ones who are going to jump. Afterward, the father, son and woman go out for ice cream. In seven terse pages—relatively long for a Keret story—the fable speaks volumes about the ways tragedy and ordinary lives exist side by side.

In “Tabula Rasa,” a Holocaust survivor commissions a clone of Hitler so he can exact revenge. Keret, the son of a Holocaust survivor, said he used technology in the story “as a metaphor to talk about humanity. The clones show that there is some kind of human instinct in which one feels morally excused to exploit them and do bad things to them.” Keret wrote the story empathically from the point of view of the clone and described the clones in general as “21st-century Jews. They are automatically judged—they don’t have any rights.”

Related

Keret’s stories are further populated with sons and daughters of all ages. In “Car Concentrate,” a 46-year-old man creates a shrine out of a Mustang that was in the long-ago car wreck that killed his father. In “Dad with Mashed Potatoes,” a group of pre-teens notices that their divorced fathers return home as white rabbits whom they can affectionately pet. In an epistolary story, Keret brings together two major themes—parenthood and the Holocaust. A young man is looking for an escape room to take his survivor mother on Holocaust Remembrance Day. His exchange with the manager, who tells him the room is closed that day, is both absurd and poignant.

“For me, talking about the relationship between parents and children is a way of talking about life,” Keret said. “I’ve just finished a mini-series in France with my wife, which is called ‘The Middleman.’ It’s a good name for a parent’s role. It tells the story of a guy who wants to be a good son and a good father to his daughter. That’s enough to create an unimaginable hell.”

Etgar Keret will be speaking at Suffolk University on Wednesday, Sept. 11. Find more information here.