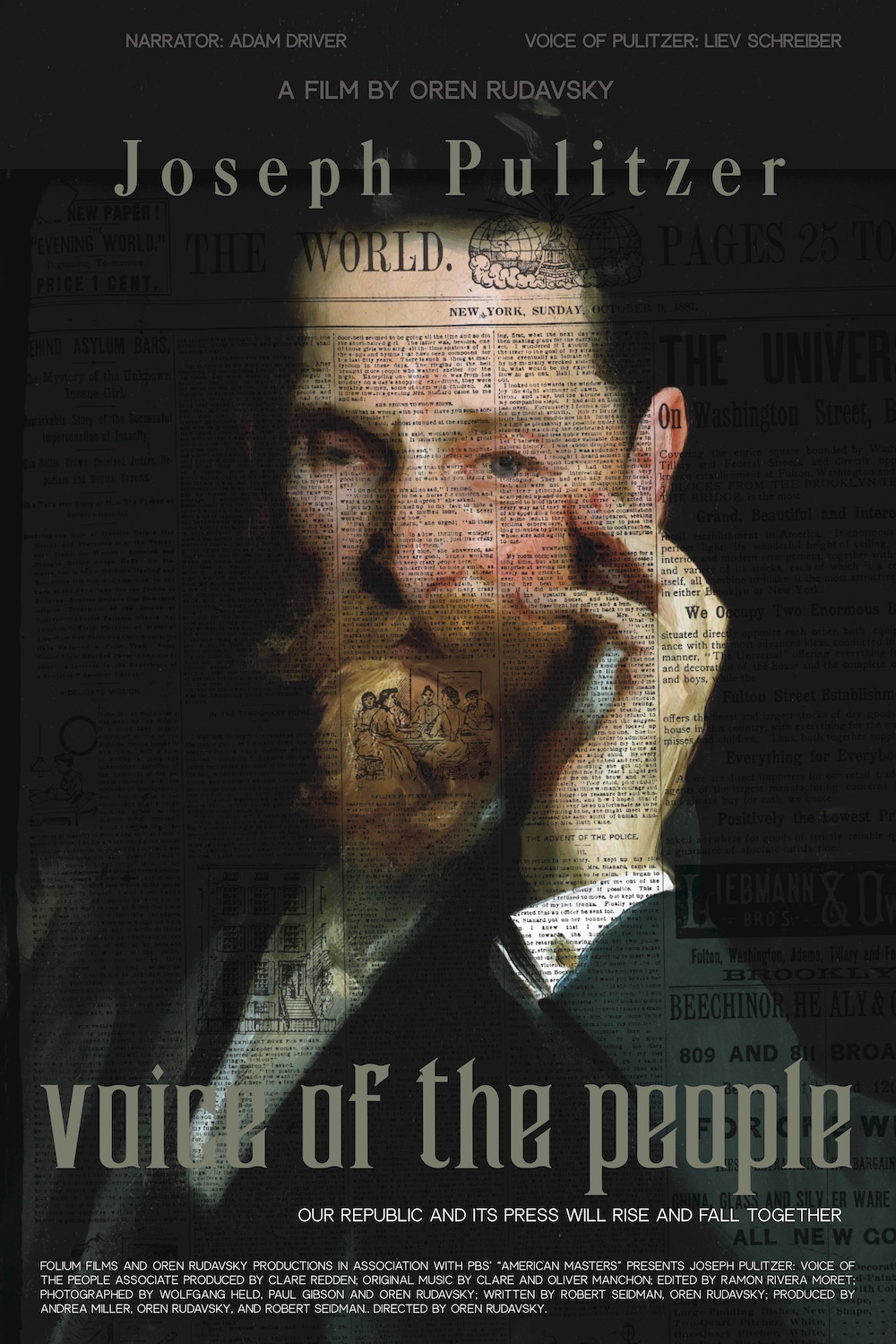

Newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer is back on the front page through a new documentary, “Joseph Pulitzer: Voice of the People,” by Newton-born filmmaker Oren Rudavsky.

A Hungarian Jew, Pulitzer immigrated to the U.S. looking to fight for the Union army in the Civil War. He embarked on a career in journalism—first in St. Louis, then with The New York World, where he battled rival publisher William Randolph Hearst—including through the notorious yellow journalism of the Spanish-American War.

Film and TV stars appear in voiceovers: Adam Driver as the narrator, Liev Schreiber as Pulitzer and Rachel Brosnahan as his standout reporter Nellie Bly. When Brosnahan joined the film, Rudavsky said, the star of “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” had “already won every award imaginable. She just really liked Nellie Bly … she was already super-famous.” And, the director noted, “Schreiber is hugely successful. Adam Driver as well. They had no reason they had to do it except that they were interested in the project.”

There’s also an array of academic experts, including Boston University professor Christopher Daly and Andie Tucher, a professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, which Pulitzer endowed along with his eponymous prizes. (Full disclosure: I attended Tucher’s course on the history of American journalism while at the Columbia Journalism School in the early 2000s.)

The film aired on PBS earlier this year, with a more recent screening at the Berkshire Jewish Film Festival this summer. “I thought the film was very well made and dealt with the important and timely issue of freedom of the press,” festival artistic director Judy Seaman wrote in an email.

Pulitzer was born in 1847, a year before liberal revolutions broke out across Europe, including Hungary. “There were progressive ideals he picked up from the 1848 revolution,” Rudavsky said. “After the failure of the revolution, people went to the States for opportunities that did not exist in Europe. I think he seized upon those.” Life in Hungary had taken a tragic personal turn for Pulitzer following the death of his father and the family’s impoverishment. He joined an influx of Jews from Europe to the U.S., in his case arriving via Boston, according to the Pulitzer Prize website.

As the film recounts, Pulitzer’s start in the U.S. was difficult, including a stint as a mule driver. He got his big break with a German newspaper in St. Louis before achieving mainstream success with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

“In many ways, he reflected the best of immigrants by how they helped build America,” said Brandeis University history professor Jonathan Sarna. “They came, they worked their way up, they made a considerable amount of money. More than today, newspapers were a very good business in the 19th century.”

Pulitzer followed up his St. Louis achievements by becoming the publisher of The New York World, transforming it into a widely read, comprehensive and progressive publication in what Rudavsky called the “fascinating” era of the Gilded Age.

“It’s the beginning of a sense of idealism, that the rich need to help the poor [and] be engaged,” Rudavsky said, “that it’s not God’s will that the poor are poor and the rich are rich. It motivated some of the thinking we discussed in the film.”

Also, Rudavsky said, “It was an era of immigrants flooding into New York—Jews.” He said Pulitzer “was from an earlier generation of Jews coming into New York who were quite assimilated.”

Professor Sarna explained that Pulitzer “did not much associate with the Jewish community in New York and St. Louis, but his opponents nevertheless sometimes smeared him as a Jew.” Sarna noted: “Newspaper publishing in [the] 19th century was something of a blood sport. Editors regularly excoriated one another, not just for their writing, but also personally, invoking stereotypes and prejudice.”

Pulitzer married Kate Davis, reportedly a cousin to Confederate president Jefferson Davis, at an Episcopal church. Although they did not raise their children Jewish, Pulitzer remembered his immigrant origins and was sensitive toward “other immigrant groups coming into the country” who “were not necessarily assimilated [or] spoke the language,” Rudavsky said.

“Plenty [of immigrants] turned their back on their own,” Rudavsky said. “Not everybody remembers their past or wants to remember.”

Yet the film does not ignore Pulitzer’s flaws—including sometimes-questionable journalistic decisions.

“I think the yellow journalism is particularly acute during the Spanish-American War,” Rudavsky said. “He battles Hearst for front-page news. Hearst spent tremendous amounts of money to be on the battlefront.” Rudavsky said Pulitzer was not as extreme as Hearst. “When the [battleship U.S.S.] Maine blew up, the Hearst papers immediately declared it was the Spanish who did it. Pulitzer held back.” And, Rudavsky said, “[Pulitzer’s] paper did not shy away from sensational stories, but [they were stories] based on fact. He made those facts colorful.”

Later in life, infirm and facing blindness, Pulitzer attacked what he saw as corruption in President Theodore Roosevelt’s Panama Canal project. This sparked a lawsuit by the president that reached the Supreme Court. Pulitzer was cleared, but Rudavsky sees similarities between that time period and the “fake news” era of today.

“You can see how easy it is in a country for democracy to be threatened when the press doesn’t stand up to leaders in Washington, or wherever,” Rudavsky said. “It is newspapers” who stand up—“the stories that are awarded Pulitzer Prizes can come from tiny little newspapers in Nowheresville, U.S., who get Pulitzer Prizes for uncovering wrongdoing,” he said. “The story of Pulitzer’s battles with Teddy Roosevelt has become emblematic for me. It’s essential to highlight in our day and age.”