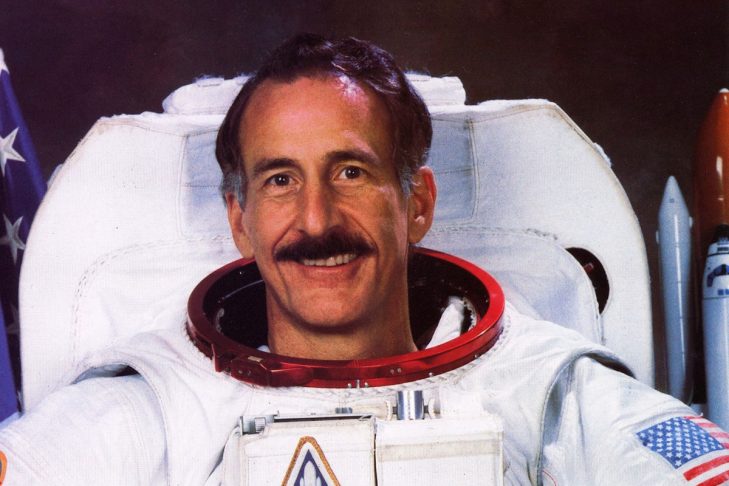

Last month, in anticipation of Simchat Torah, the Jewish Arts Collaborative brought together a rabbi and an astronaut in conversation—Leslie Gordon of Temple Aliyah in Needham and Jeff Hoffman, who now teaches in the department of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT. Over Shabbat dinner, the two presented a program they called “Big Bang Beresheit” for an audience of over 70 people.

Simchat Torah is the time of year when Jews celebrate ending one cycle of Torah readings and begin another anew with the first chapter of Genesis, or Beresheit. To visualize how impressive this milestone of reading the entire Torah is, I once saw a Torah scroll completely unfurled, and it was stunning—here was 5,000 years of past, present and future wisdom handwritten on parchment stitched together.

When Hoffman first went up into space in 1985, he was determined eventually to bring a Torah back to space. “Going into space,” he said at the Shabbat gathering, “represents the future to me, and Judaism goes back thousands and thousands of years. There was something unique about joining this old tradition with something that was so futuristic. That’s what led to the idea of initially flying Jewish religious articles to take with me in space.”

But Hoffman’s Jewish space venture had a rocky start. On that first flight, it was Passover and bringing a box of matzah with him was impractical. “Think about crumbs in space,” joked Hoffman. On later missions he brought up a mezuzah that he put up with Velcro, and the atarot (embellishments) from his son’s tallisim (prayer shawls). The atarot had particular meaning for the astronaut’s family: One atara quoted the verse in the Book of Job that mentions Orion, and the other Elijah’s ascent to heaven in a fiery chariot.

When Hoffman’s space mission in 1993 to fix the Hubble Space Telescope coincided with Hanukkah, he took up a dreidel donated by an artist in Jerusalem, as well as a traveling menorah. With cameras rolling in the shuttle, Americans saw Hoffman teaching his crewmates how to play dreidel.

It wasn’t until Hoffman’s last mission that he finally got his wish and brought along a Torah. But getting to that point had been a challenge. There was a size limitation on what Hoffman could bring on the shuttle. His rabbi in Houston spent years looking for a small kosher Torah. And then on a trip to New York he met a man who had bought a mini Torah from a scribe in Jerusalem 25 years earlier. For all those years, the man could not bear to sell the Torah. But once he was made aware that it was the ideal size for Hoffman’s purposes, he knew he had saved it for the right occasion.

After acquiring the Torah, there was the question of which portion to prepare to read in space. Given that shuttle flights are frequently delayed, selecting a chapter to coincide with a particular Shabbat would be futile. Instead, Hoffman decided on reading the first chapter of Genesis (Beresheit). “You can’t go wrong,” he told his Friday-evening audience. “It’s the beginning of the Bible, and since it’s the first time a Torah went into space, it was appropriate.” He further noted that of all the Jewish objects he brought into space over time, taking the Torah into the heavens was a unique experience. “It made space special to have the Torah with me,” he said. “We all carry our cultures and traditions with us, and that’s what I was doing. And I’m delighted the Torah is still in use at my former congregation in Houston.”

Elaborating on Hoffman’s talk, Gordon offered sage interpretations of the first two chapters of Genesis that Hoffman read in space. In her brilliant exegesis, she pointed out that those first couple of chapters chronicle two distinct myths, or narratives, about creation. According to Gordon, the first narrative commands humans to be fruitful and multiply and then rule over creatures on earth. The second version reflects on humankind stepping back from creation to till the soil and simply watch over the world.

Adam, the first man, has a different role in the two creation stories. Gordon taught that in the first version Adam is the crowning achievement of a creation wrought by an ambitious deity. In the second version Adam is created first and a more laidback God gets his hands dirty by actually forming the first man and making Adam the humble caretaker who watches over the earth.

Gordon noted: “In a modern literary work, these contradictory accounts would be intolerable. An editor would ask: ‘Was Adam created first or last? Was he the pinnacle of creation or the impetus? Was creation achieved by speaking words or were hands really making stuff?’ Jewish thought can tolerate these mismatched accounts because both of these myths have truth to them and both are needed to capture the fullness of creation.”

For Gordon, science and theology are not at odds. She asserts that the creation myths of Genesis complement the Big Bang theory, rendering a complete account of creation. Furthermore, in the daily morning liturgy, God is praised for renewing creation each and every day. “Those of us who are here,” said Gordon, “fill the world and conquer it, as well as tend the earth and guard it.”

For Hoffman, viewing the world from space brought on a profound sense of awe. “It’s you and the universe—a perspective that is so different from anything you’ve seen before,” he said. “We are partners in each day’s newly created world.”

Watch Hoffman read from the Torah in space:

Watch Hoffman spin a dreidel in space:

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE