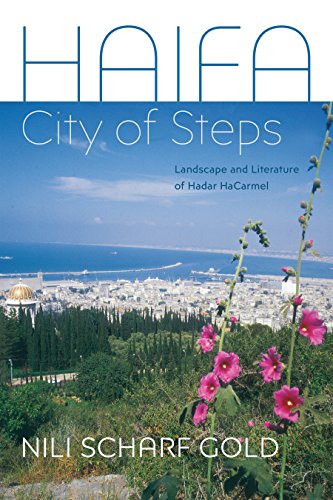

In “Haifa: City of Steps,” Nili Scharf Gold, a professor of Hebrew literature, pays homage to her hometown through its architecture, history and literature. Bostonians will be especially appreciative of having a more intimate acquaintance with its sister city. Scharf Gold recently spoke with JewishBoston about her book and the things that make Haifa a distinct and dynamic city.

In the book you spend a lot of time describing Haifa’s architecture. What are some of the more striking buildings for you?

One of my favorite buildings is the municipal building. In Hebrew, it’s called the “Temple of the Municipality” in Haifa, versus the “House of the Municipality,” the usual term for it in the rest of the country. That tells you something about the approach of Haifa’s residents to this building. It has an important status. I remember walking into the municipality, where I hadn’t been since I was 5. The floor was still red marble, just as I had remembered.

The municipality was the core of Arab-Jewish relations in Haifa. The mayor at the time the municipality was built was Hassan Bey Shukri. The main street where the municipality is located is named after him. I was in awe of the way he governed [from 1914-1940]. He embraced the Jews, who were a minority at the time. These buildings are a testimony to the cooperation between Jews and Arabs, as well as to equality.

Haifa is thought of as a place where Jews and Arabs have lived together in peace over the years. That wasn’t always the case, was it?

Haifa has been relatively peaceful for Arabs and Jews. During the mandate, there were Arab revolts in the late 1930s. In other mixed cities the municipality stopped functioning at that time, but Haifa was the only place that continued to operate. Nevertheless, the Jews ran away in 1929 and 1936, which gave rise to two important modernist buildings built as a result of those riots. Jews were afraid to go down to the markets in the lower part of the city where the Arabs were. Leaders of Hadar HaCarmel—Haifa’s Jewish neighborhood—decided to build two markets in their neighborhood—the Commercial Center and the Talpiot Market. Both those buildings are important in the history of architecture as a result of those riots.

At the same time, Jews and Arabs sat on the city council together. Hassan Bey Shukri always insisted on having a Jewish deputy. When Shabtai Levi became the first Jewish mayor of Haifa, he made sure to have an Arab Christian and a Muslim as deputies. From the time the Alliance School was established in 1881, there were Arab students and the Jews of Haifa spoke Arabic.

But there was also the tragedy of 1948 when the majority of the Arabs left. You can call it expelled, chased away, ran away—call it whatever you want. The Arabs felt they had to leave and were not allowed back. Moreover, David Ben-Gurion gave an order to demolish the entire Arab Old City in Haifa. However, he ordered Shabtai Levy to destroy the Arab neighborhood, Levy refused. So the army went in and did the job. It’s important to note that non-Haifa forces did the destroying. Some Arabs stayed in Haifa and others went to the Galilee. Now, with the Jewish nation-state law, the big demonstrations against it are in Haifa, where Jews and Arabs are protesting together.

You present Haifa through the lens of a number of writers, including Yehuda Amichai, Dahlia Ravikovitch and A.B. Yehoshua. Which of these writers exemplifies Haifa for a reader who doesn’t know the city?

I have a hard time choosing! Yehoshua is the most consciously aware of the greatness of Haifa. When I interviewed him in a suburb of Tel Aviv, where he recently moved to be closer to his children, he felt exiled from Haifa. He’s 80 now and was born in Jerusalem, but lived in Haifa for 40 years. He showcased the city in his books. In his novel “The Lover,” he even makes a cameo appearance like Hitchcock did in his movies. In one scene a girl cannot fall asleep and looks across the wadi, or valley, where she sees a light. There is a man typing who is clearly Yehoshua.

Dahlia Ravikovitch lived in Haifa as a teenager the same years I lived there. Her poems about Haifa indicate the way I remember the city. She describes how the groves with their treetops run to the sea. When you stand on top of the mountain in Haifa, you have the feeling that the treetops are like rounded backs of sheep that go down. Also, like me, Ravikovitch lost her father at a young age. That very much determined who she became, just as the death of my father determined who I was.

I don’t agree with Sami Michael politically—he’s much more to the left, more than I am, but he is the kindest man and head of the civil rights movement in Haifa. Now in his 90s, he was born in Iraq and very much identifies as an Arab Jew. When he started out as a writer and journalist, he wrote in Arabic. It was only until he was in his 30s and 40s that he started writing in Hebrew. His view of Haifa is that of an open city, a tolerant city.

Yehuda Amichai, who lived in Haifa in 1947, was not aware he was writing about Haifa. The love letters he wrote to his girlfriend, who was in the United States, are really love letters to Haifa. In one letter he describes two mountains as breasts. In another letter he describes the boats in the bay releasing smoke, which made the bay look like a kitchen before a holiday. His imagination is endless. However, there is only one poem in which he mentions Hadar HaCarmel. In that poem he talks about how the role of the café is important to him, and it’s very much the way I remember the café in Haifa. It was a hiding place, a safe place. My mother used to take me to a café. That’s where she taught me to read her German journals.

The Technion comes across as the most influential building in Haifa. Why is that?

The Technion is where everything originated. Haifa was built around it. It’s the Israeli MIT. When the school moved out of Hadar HaCarmel, the original building stood desolate for years. It was eventually restored and today is the National Israel Museum of Science, Technology and Space for both children and adults. The building itself was designed by a German-Jewish architect in 1912. He merges European and Middle Eastern architecture, reflecting his belief in a peaceful co-existence. During World War II, Technion students helped the British develop technology. The building is also described in Amichai’s letters and plays a role in Israel’s War of Independence. The fact that Haifa was chosen to house the Technion indicated that it was recognized as a place of relative peace and neutrality, even during the Ottoman Empire.