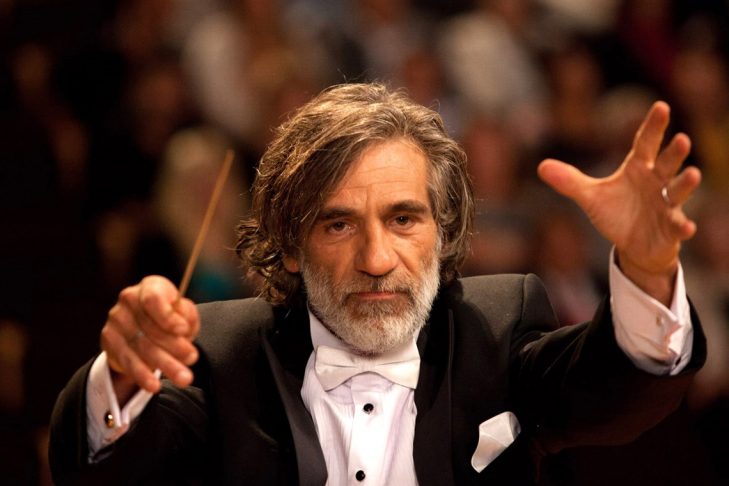

The mythic story of perhaps the world’s most famous love triangle—Abraham, Sarah and Hagar—is the framework on which director Ori Sivan builds his film “Harmonia.” The story is recast in modern-day Jerusalem with Abraham as the conductor of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. His wife, Sarah, the orchestra’s harpist, has been struggling for years to have a child. Hagar, an Israeli-Arab from East Jerusalem, joins the orchestra as the third chair French horn player.

Hagar plays her instrument so softly that the musical notes are as ethereal and as unassuming as she is. And while the written biblical references to the trio that flash on the screen between scenes may initially seem heavy-handed, “Harmonia” is a nuanced and subtle film in both plot and message. That subtlety begins when Sarah and Hagar bond as intimates and develop a relationship bordering on the romantic. Hagar is with Sarah as she miscarries early in the film, and she embraces Sarah’s pain as her own.

-

At this point, the audience, which has been made well-aware of the biblical story, knows Hagar will offer to have a baby for Sara. Unlike in the biblical telling, however, Hagar’s gesture in the film is one of pure love and generosity. She gives birth to a son, whom Abraham and Sarah name Ben. Like his biblical forebear, Ben is a wild child, all mania and motion as he roller-skates his way around Jerusalem. He is a pianist who plays so exuberantly, so frenetically, that his energy comes across as menacing and feels as if it is bordering on violence. He is beyond Sarah and Abraham’s control and can’t find a place for himself in their affluent, staid household.

After a lengthy absence, Hagar returns to the orchestra, where she observes her son from afar. In keeping with the biblical story, Sarah gives birth to a son beyond her expected childbearing years. Isaac is angelic, doted on and anointed as a violinist by an overbearing Abraham. Symbolism and foreshadowing are used to great effect here: When Sarah poses with baby Isaac for a poster announcing her Carnegie Hall debut, one of the shots captures Ben lurking in the corner. His image is blurry, hulking yet ultimately tragic; he has no place in this new configuration of his family.

Director Sivan expertly deploys his knowledge of the classical musical world throughout “Harmonia.” Unsurprisingly, this film is not his first foray into integrating classical music in his work. In 2001, he made a documentary about Klari Sarvash, the first harpist to play with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. He made another in 2010 about the great Zubin Mehta, the Israel Philharmonic’s inimitable maestro.

Sivan’s choice to thread Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s symphonic suite, “Scheherazade,” throughout the latter part of “Harmonia” lends a fairy-tale quality to the narrative. The symphony, based on “One Thousand and One Arabian Nights,” recalls the story of Scheherazade, a woman who tells her husband, the king, a new story each night to stay her execution. To Scheherazade, storytelling equals survival. Storytelling is malleable and the truth bears no relation to hardboiled facts. Sivan makes this clear as he twists and bends the Abraham-Sarah-Hagar story to depict the larger reality of Israeli-Palestinian peace.

Ben eventually breaks away from Abraham and Sarah and, like in the biblical story, goes into exile. He lives with Hagar in East Jerusalem, where his musical genius unfurls in his spirited playing of piano and guitar. He sheds his Jewish identity and adopts the name Ismail.

Isaac has become an obedient yet timid boy. He has fulfilled his father’s wish and plays the violin proficiently. In a scene toward the end of the film, Abraham senses his son is holding back musically and pressures him to ramp up his playing. Abraham tells his young son to affect a playing style that encompasses “restraint and passion, order and chaos.” Abraham’s observation alludes to the tension that has been present throughout the film. It is there in the early stages of the love Sarah and Hagar once had for each other. It is there in the way Abraham leads his orchestra. And it culminates in the relationship between Ismail and Isaac.

The brothers are eventually united on stage, where Isaac finally plays his violin somewhere between technical virtuosity and passionate interpretation. Ismail is not only Isaac’s muse, but also his guide. The historic enmity between the children of Ismail and the children of Abraham fades away as the last musical notes of the film linger. “Harmonia” is not so much the recasting of a biblical story as it is a sophisticated retelling of a classic myth that brings forward fresh possibilities for peace and love.

“Harmonia” is the opening film for the Boston Jewish Film Festival’s Summer Cinematheque, which begins July 12. Find tickets and information here.

Never miss the best stories and events! Get JewishBoston This Week.