The family can be an incubator of secrets. Perhaps no one knows this better and depicts it more gracefully than the memoirist Helen Fremont. Fremont has not only grappled with family secrets all her life, but she has dealt with the emotional fallout of both discovering them and then revealing them to the world in her affecting memoirs.

Her first memoir, “After Long Silence,” published more than two decades ago, uncovered the fact that her Catholic Polish American parents were actually Jewish survivors of the Holocaust. After Fremont told her story, her family branded her a traitor. When her father died four years after the publication of the book, she was not only disinherited, but also declared legally predeceased in a codicil to her father’s will.

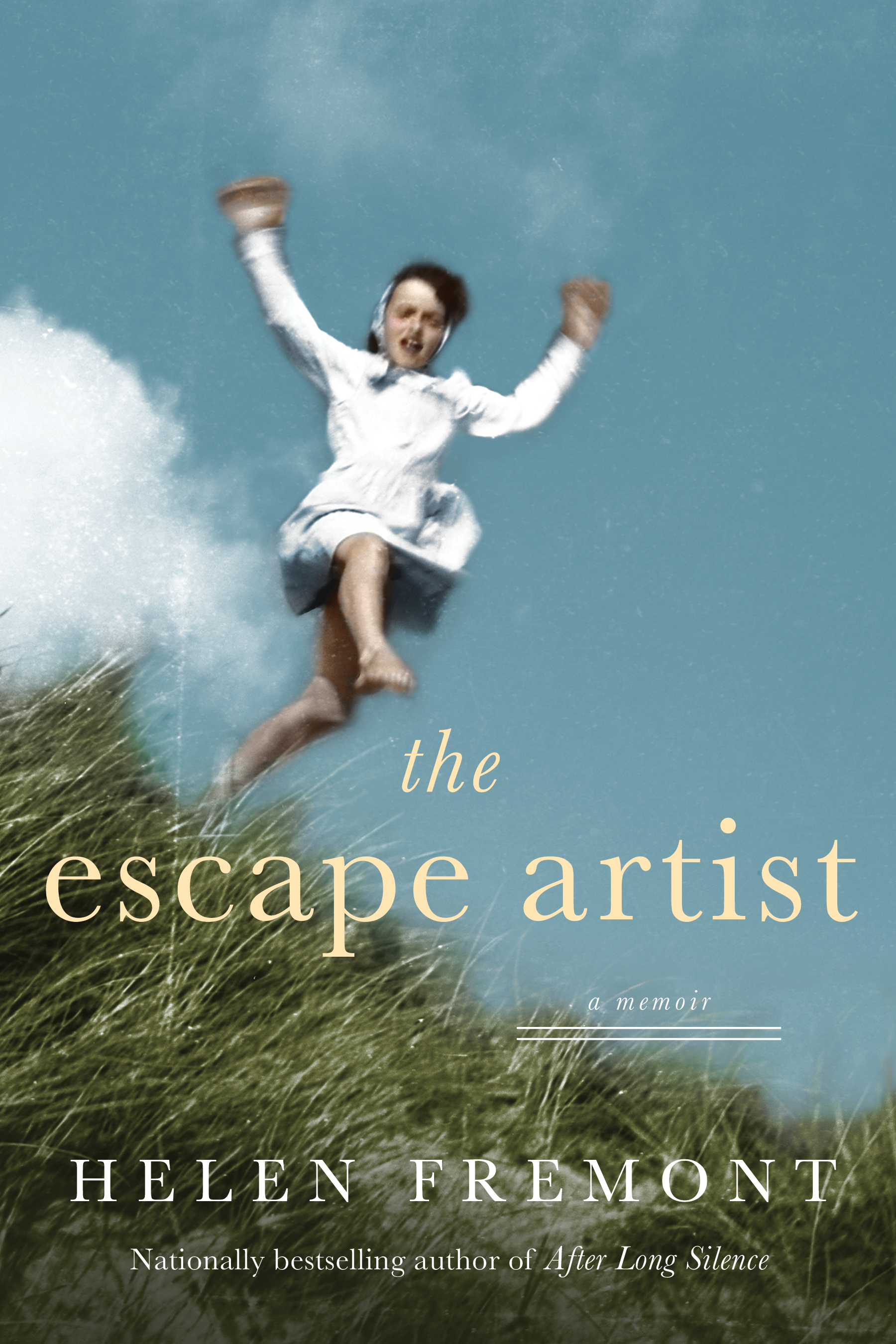

Deleted from her family’s narrative, Fremont was determined to restore her rightful place in the story. “The Escape Artist,” her new and compelling memoir, is that story. Fremont and her nuclear family—mother, father and sister—functioned as a tight, claustrophobic unit. To all appearances, her father was a successful doctor, her beautiful mother a housewife and their two daughters bright, successful young women.

What went on behind closed doors was another story. Fremont’s father escaped the Soviet gulag, where he had been imprisoned for six years. Her traumatized mother disguised herself as an Italian soldier and was eventually reunited in Rome with her sister, Zosia. Fremont’s sister, Lara, had her own mental health struggles. Fremont, as a witness and confidante, had intense emotional and physical responses to those stressors.

In anticipation of her book launch at Brookline Booksmith on Tuesday, Feb. 11, Fremont spoke to JewishBoston about her memoir, her complicated family history, the pressure of keeping secrets and what propelled her to continue to uncover the truth.

Your book is part memoir, part literary detective novel and an imagining of the past. How did those three things come together for you?

This book took much longer to write than “After Long Silence.” I used my imagination more in this second book to try to see my family’s reactions to these ongoing secrets. Writing is the way I think and figure things out. I stumbled upon so many family secrets. I’m a criminal defense lawyer, and it was a matter of pulling pieces of evidence and looking at those pieces as I tried to attach motives to the storytelling.

Your mother called you “the escape artist” because you were always trying to get away from your family. Is that an accurate description?

My mother said that when she thought I was turning my back on our family. Our No. 1 rule was loyalty. That rule stemmed from what my parents went through in the war. During that time, the only people you could trust were your nuclear family. If you were not loyal to them, you were literally dead. For my parents, there was no greater sin I could commit than spending time with friends. The family is the small, indivisible unit in humanity. But as a teenager, all I wanted to do was be with my friends. I couldn’t wait to leave my family. It’s ironic that after I left home at 17, the real world felt very scary.

There were also so many escapes in my family. My father would have died in Siberia if he hadn’t escaped in 1946. My mother disguised herself as an Italian soldier to flee Poland. For my mother, the word “escape” was so loaded and guilt-inducing. Escaping enabled her to live, but she couldn’t live with herself for having escaped. She always said, “I should have died in the war.”

Was it difficult for you to imagine your parents’ pasts?

It was really traumatic to go back and imagine my parents’ pasts. I think that’s why it took so long to write this book. I would try to write a discrete scene of an argument, and I would get so upset or nauseated. Consequently, I do a lot of self-care by going to the gym, running and rowing. When I realized it was too painful to write a particular scene, I would remember something less volatile. When I circled back to the difficult scene, I paid attention to the craft of writing as opposed to what actually happened. I could remove myself a bit from the physical and emotional event. Retelling the story helps to find a container for it, and a book is the ultimate container for these difficult feelings.

Your father disowned you, and you were described as “predeceased “in his will. How did that affect you?

Even though I’m a lawyer, I couldn’t take in this legal document. The codicil is the single and last page of my father’s will. On that piece of paper, my name was repeatedly deleted. It was such a blow; I was stunned into silence. I couldn’t write that scene [about the will] for a long time. The whole thing was nefarious. To be designated as predeceased, it required the collaboration of my entire family. As I found out years later, my mother signed an identical will. But I thought my father and I were allies. He supported me in writing “After Long Silence.” It was particularly cruel that all of this came to pass through my father’s will. It was the clean and carefully planned deletion of a person. Although I was written out of the story, it was also incredibly freeing to realize I don’t have control of how others will react to my work.

In the book, your mother said your family “was held together by the great glue of suffering.” Does that resonate with you?

Our family was almost like a cult because we were so separate from everyone else. It was a life of extremes. I am suffering a whole lot less now that I’m out of that suffocating, loving family. I’m living a life that feels real and true to who I am. That was something I could never do before. There have been studies of Holocaust survivors and second-generation survivors that have found that when they are separated from their families, they are traumatized. When I decided to join the Peace Corps, I was treated as if I were never coming back. Any separation that occurs in a family of survivors is like a death, and that can be terrifying.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Helen Fremont will read from “The Escape Artist” at Brookline Booksmith on Tuesday, Feb. 11. She will be at Belmont Books on Friday, March 20, and in conversation with author Helen Epstein at Porter Square Books on Wednesday, March 25.