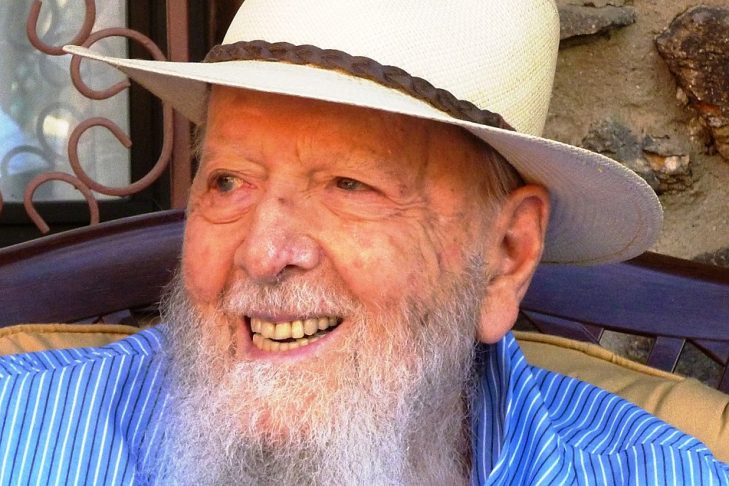

Family lore has it that my father’s sister, my Aunt Gladys, dated Herman Wouk. After a couple of dates, my assimilated aunt decided the Orthodox Jewish Wouk was “too religious.” Wouk, however, had a special status in my father’s library. My dad voraciously read Wouk, and his favorite book was “The Caine Mutiny.”

Wouk died on Friday, May 17, at the age of 103. In 2015, I wrote about him in connection with the 60th anniversary of what is arguably his most famous book, “Marjorie Morningstar.”

Jonathan Karp, his editor at Simon & Schuster, told NPR that Wouk was “the Jackie Robinson of Jewish American fiction. He was on the cover of Time magazine for ‘Marjorie Morningstar’ and he popularized a lot of themes that other writers—like [Saul] Bellow and [Philip] Roth and [Bernard] Malamud—would deal with in their novels.”

Wouk’s popular bent may not have earned him the literary gravitas of Bellow, Roth or Malamud, but his work carried weighty themes that included the Holocaust, war and Judaism. Wouk won a Pulitzer Prize in 1951 for “The Caine Mutiny,” leaving a wealth of literature that generations of readers will discover.

Lessons From the 60th Anniversary of “Marjorie Morningstar”

When I was a young teenager in the late 1970s, my father forbade me to read “Marjorie Morningstar,” Wouk’s novel cum saga that chronicles the eponymous Marjorie’s coming of age in the Upper West Side of the 1930s. The book was initially published in 1955. But I furtively read my grandparents’ Reader’s Digest condensed edition, not quite understanding what my father found so objectionable about the book. Marjorie, the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who worked their way out of the Bronx to Central Park West, is introduced as a willful, beautiful teenager with a bevy of admirers. In her new social circle, she graduated from dating City College boys to keeping company with young Columbia men; she left the boy whose father owned a garage in the Bronx for one who was a department store heir.

Marjorie eventually falls in love with Noel Airman, a man 10 years her senior. Noel has some success as a songwriter but fails miserably as a playwright. He’s an assimilated Jew who has changed his name from Saul Ehrman to conjure Noel Coward. I suspect that Marjorie was forbidden to me because I was too young to read about her love life, which included numerous “necking” sessions with various boys and ultimately an affair with Noel. But I was persistent, and my loving grandmother was unconditionally supportive of my voracious reading habit. (“Love Story” was another book on my banned reading list that she slipped to me.)

Forty years later, as the novel turned 60 and Wouk celebrated his 100th birthday, it was the right time to revisit the work that made such a deep impression on my father and me. On this go around I realized how uncomfortably close to home the novel was for my father, who also came of age in the 1930s and ‘40s. Marjorie was a forerunner of the women’s movement, and my much-older father was initially baffled by what he called “women’s liberation.” Yet he was supportive of my much-younger mother’s decision to go back to school. In that sense, my ambitious mother was a version of Marjorie.

My father was also just a generation into the American dream like Marjorie’s family and Wouk’s parents. Like Wouk, my father was a veteran of World War II and a naval officer. Both were Jews and Ivy League graduates. Wouk, a New Yorker, had gone to Columbia, and my father, a New Haven boy, graduated from Yale. Both were caught up in the maelstrom of war and came out the more patriotic for it. Through the war, they were pulled out of their circumscribed lives and saw a world that was more exotic and even more stratified than the Ivy League.

My family, the Boltons, even had a passing acquaintance with the Wouks. My Aunt Gladys claimed that she dated Herman in the early 1930s when she was a student at Connecticut College for Women. She swore that Marjorie was a composite of her and Wouk’s sister, Irene. She confessed to rejecting Wouk because, as she put it, he was “too Jewish.”

That wasn’t surprising to me since I knew how intent the Boltons were on assimilating into American life. My grandfather changed the family name from “Bolotin” so he could pass as a WASP at Yale in 1910.

No doubt my family history, my father’s identity as an assimilated Jew and his adamant response to Marjorie influenced my adult response to the book. But in the end, it is younger Marjorie as a feminist that strikes the deepest chord with me. As early as the age of 16 she anticipates egalitarian Judaism when she’s aware of how male-centric the world is. At her brother’s bar mitzvah, she has an epiphany that Judaism “was a masculine thing…the very word Hebrew had a rugged male sound to it.” As a naïve Hunter College graduate, Marjorie soon after understands that the trajectory of her acting career is determined by men. She tries to buck the system, and much of the narrative shows her ongoing efforts to be more than a rich, spoiled girl, to make it on her own.

After all these years, Marjorie is still impressive to me as she swims in the pool of a kosher resort on Long Island in a daring flesh-colored swimsuit. And after her on-again, off-again courtship, an older Marjorie agrees to have sex with Noel, though she is not particularly in the mood. But she is in control, and this kind of verisimilitude resonates throughout the decades.

I suspect that my father had both scenes in mind when he censored my reading. But it goes deeper than that. I think, in the end, my father was a closet feminist. After all, adult Marjorie’s seeming dependency on a man did not sit well with him. And I suspect Marjorie and Aunt Gladys appeared to be ultimately successful for reasons that made him wince. Marjorie was also about mixed expectations, and my father didn’t want her in my life at an impressionable age. He also didn’t want me to be just another pretty face.

But now I see that my father missed teaching me one of the novel’s more profound lessons. Despite ending up in suburbia with prematurely gray hair, for most of the novel Marjorie defied convention. And she continues to do so as she approaches her seventh decade.

A longer version of this article was published in The Forward in 2015.