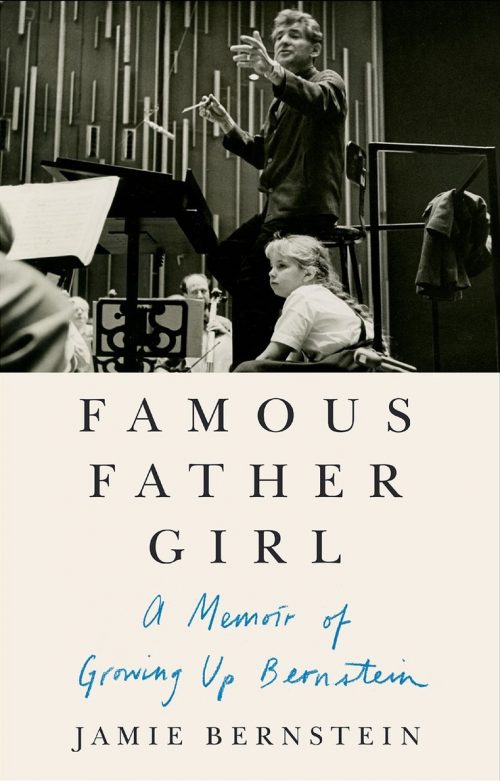

In this year of Leonard Bernstein’s centenary, his oldest daughter, Jamie, has written an intimate, loving, moving and deeply honest memoir, “Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein,” about growing up with her complicated maestro father. The book’s brilliance stems from the fact that Leonard’s story does not overshadow Jamie’s. Jamie grew up privileged and wealthy, but she became a talented writer, documentarian and fine musician in her own right. She loves her father dearly but can find him overwhelming and flawed. This is not a tell-all book, exactly, but an insider’s view of life with a complex, loving and often indulgent man. Jamie Bernstein recently spoke with JewishBoston about growing up as a Bernstein and her father’s enduring legacy.

What has your father’s centennial been like for you, your brother and sister?

It’s very gratifying that the whole world is joining these centennial celebrations with such enthusiasm. My siblings and I are constantly trying to participate in as many centennial events as possible. At last count the database in the Bernstein office indicated there were over 3,500 events worldwide. Obviously, we can’t attend them all, but we do as much as we can.

Your father was a 20th-century composer and yet a role model for today’s composers. Tell us about that.

In the mid-20th century my father was not composing music of the day. At that time, if you wanted to be accepted by the musical academic pundits, the conservatories and universities, you had to write only 12-tone music that was not in a key and had no melody. It’s cerebral, like math—there is no emotionality in it. My father knew how to write 12-tone music compositions. He used it from time to time; it was one of the many colors on his composition palette. But he didn’t want to feel restricted to writing only that way. He continued to write melodies and mix up different genres. By doing all this he consciously disqualified himself from being a so-called “serious composer” in his lifetime. Today’s composers no longer feel straightjacketed like that and are completely free to write in any idiom or genre; they can mix them all together. Today’s composers look back at Leonard Bernstein and feel he’s a much more relevant role model for them than the 12-tone composers are.

The title of your book comes from a classmate who derisively called you “famous father girl.” Why did the phrase appeal to you as a book title?

The reason I like this title is that there is something a little weird about it. It’s like a poke in the eye, and that amuses me. I also like the way it makes the reader have no illusions what this book is about. I didn’t want to be coy about having this illustrious father; I put it right out there. The book is how I made my peace with music and who my father was.

Why wasn’t your grandfather initially supportive of Leonard’s musical ambitions?

My grandparents were Jewish immigrants. My grandmother, Jenny, came from Poland and Russia with her family when she was 8. My grandfather, Sam, came by himself [to the Boston area] at the age of 17. His was the classic immigrant story, arriving in this country without a kopeck in his pocket. Sam had a beauty supply company and was a successful businessman who got his family through the Depression. He wanted nothing more than to turn over business to his oldest son, Leonard. But Leonard wanted to be a musician, and this was a big problem for Sam because in the old country, a musician was a “klezmer”—a wandering vagrant, playing any kind of music anywhere. Sam thought he hadn’t come all this way just so his son could be a penniless musician.

Related

What did Judaism mean to your father?

My father found his own way to be Jewish. He married my mother, Felicia Montealegre, who was raised Catholic in Chile. When we were growing up we never belonged to a synagogue. That had a lot to do with the fact that we had a country house in Connecticut where we spent weekends, and going to a synagogue would have interfered with that routine. But on Yom Kippur my father always went to temple with my brother. Passover seders were big family events where we expressed our Jewishness. We lit Hanukkah candles with a Christmas tree in the background. We even lit a menorah the first night of Hanukkah in the Carter White House before the Kennedy Center Honors.

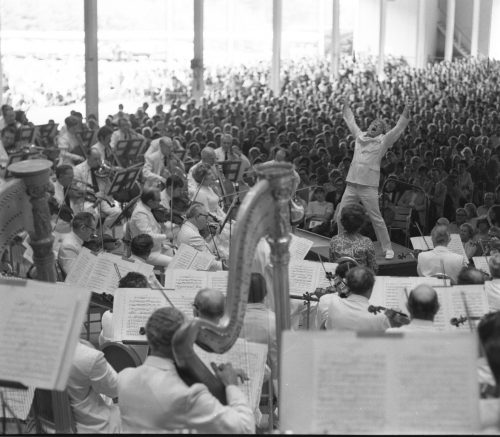

Why were your father’s signature Young People’s Concerts so important to him?

Those [televised] concerts were important to my dad because he was such a compulsive teacher. Teaching was his default mode—no matter what he was doing, he was always teaching. He could be rehearsing an orchestra, telling a Jewish joke or reciting Lewis Carroll—it was always coming from that same essential impulse to grab you by the sleeve. That’s why he was such a good teacher. During the Young People’s Concerts, that quality of reaching out and tugging you on the sleeve was completely palpable on the television screen.

How are you continuing your father’s legacy of reaching out to young people?

One of the things I love doing in this centennial year is talking to young people about my dad. This generation may not know who he is, so I explain to them that entire families sat in front of the single screen in their living room to watch the Young People’s Concerts. That was how multiple generations of viewers became classical music fans—many of them were exposed to classical music for the first time through these concerts. Then I tell young people to think how many multiple screens they have in their homes. I point that out to show them how different the world was and how amazing it was that my father and television came along at the same time.

The basis of your wonderful documentary, “Crescendo: The Power of Music,” is about giving music to successive generations. What did making the documentary mean to you?

When I discovered the existence of El Sistema Youth Orchestra for Social Change in Venezuela, I went crazy with excitement. I went down there to see it with my own eyes. All I could think about was if only my dad was alive to see this. El Sistema was everything he cared about all rolled up into one. Making the documentary was a way of telling my father what was going on with El Sistema and telling him it was coming to the United States. I was acting as his eyes and ears.

What is an important part of your father’s legacy?

One of the things my father worked for his entire adult life was to make the world a better place. He was an activist from the get-go, and as a result his FBI file was 800 pages long. The FBI had been tracking him for over 40 years, and with the Freedom of Information Act, he finally saw his file. His activism and his sense of trying to make the world better really informed everything he did, including his music. He really subscribed to tikkun olam—repairing the world. That sensibility was so much a part of who he was. You can track it through his music, his writings and what he spent his life doing.