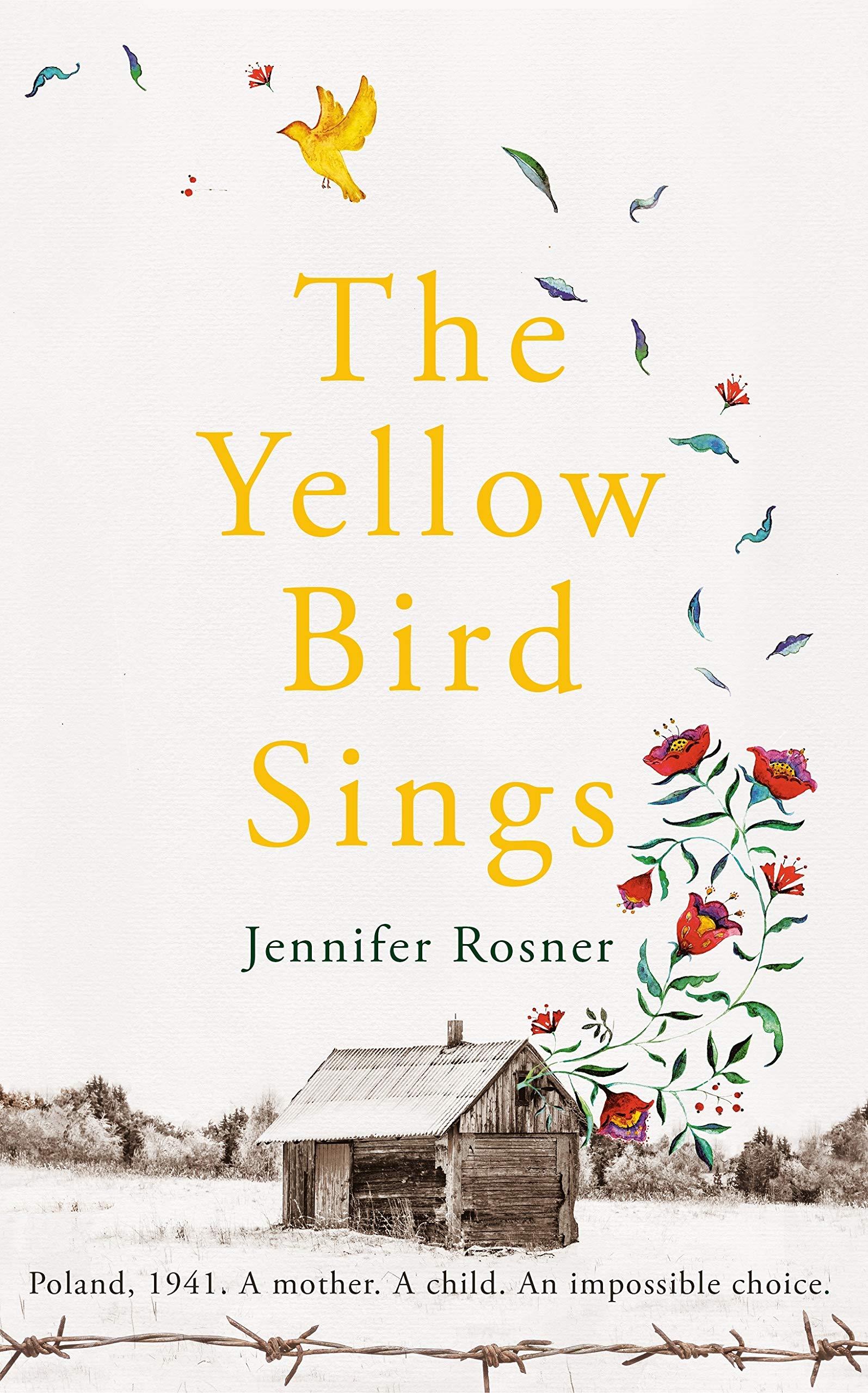

When the world “ceased to make sense,” Róza and her 5-year-old daughter, Shira, fled their small Polish town and took refuge in the barn of a local family whom Róza casually knew as customers from her mother’s bakery. This is the barebones premise of Jennifer Rosner’s beautiful novel, “The Yellow Bird Sings,” set in Nazi-occupied Poland.

Rosner delicately works with the premise that the mother-daughter duo must stay completely silent, which is especially difficult for a young child under any circumstance. But it is that much harder for young Shira, a musical prodigy. Shira, whose name means “song” in Hebrew, can play out entire musical compositions in her head, which “take shape and pulse through her, quiet at first, then building in intensity and growing louder.”

Róza continuously telegraphs the consequences of making noise to her young daughter. The Nazis have murdered her young violinist husband and her parents have been deported to their deaths at Auschwitz. Róza and Shira’s lives hang in the balance and depend on the frightened and equally ambivalent family hiding them. Their fragile safety comes at an unbearable price. Every night, Henryk, the farmer, rapes Róza, the cost for allowing Róza and Shira to hide in his hayloft.

Those horrific scenes with Henryk make “The Yellow Bird Sings” dramatize a shocking, mostly unspoken realism of the Holocaust. Yet Rosner’s novel is also a profound commentary on how art saves lives under the direst of circumstances.

The titular yellow bird stars in the captivating fairytale that Róza invents to distract Shira from making noise. The yellow bird is Shira’s imaginary companion and stays by the girl’s side as it warbles the original compositions Shira is forbidden to sing aloud.

Rosner, who lives in Northampton, is the author of a previous book, “If a Tree Falls: A Family’s Quest to Hear and Be Heard.” The book is Rosner’s memoir about raising her two deaf daughters.

Rosner will be a guest on Quarantine(ish) Book Talks on Thursday, July 30, at 8 p.m. She recently spoke to JewishBoston in anticipation of her virtual appearance co-produced by Jewish Women’s Archive (other upcoming appearances can be found here). Highlights of the conversation include her research on hidden children in the Holocaust and the “resonant “connections between her two books.

What were some of your inspirations for writing “The Yellow Bird Sings”?

I talked about “If a Tree Falls” at an event sponsored by the Jewish Book Council, explaining how we were working with hearing technology and getting our daughters to vocalize. We encouraged every sound they could make, even if it was screeching at a restaurant or laughing in the library. Afterward, a woman told me about her experience as a child having to be completely silent in a shoemaker’s attic with her mother during the Holocaust. I couldn’t stop thinking about that woman. After I met her, I interviewed other children hidden during the Holocaust. My research eventually brought me to Poland and Tel Aviv.

The contrast between your novel and your memoir is fascinating. On the one hand, you taught and encouraged your children to make sounds. Yet Shira couldn’t make a sound and had to internalize music.

What’s interesting is the notion of having to be hidden or having your child have to vanish in a certain way. I think this resonated with the fear I had about my ancestors. Although my novel is historical fiction, it’s a line that ran through my memoir, so it was doubly resonant. Shira’s life contrasted with how we were working with our children, and it brought up the hiddenness that deaf people often experience.

The Holocaust genre, whether it’s fiction or non-fiction, is a crowded landscape. What made you brave it as a writer?

There was so much resonance in having met this hidden child of the Holocaust. When I decided to make Shira a musical prodigy, I learned about Amnon Weinstein in Tel Aviv, a violin-maker who has been rescuing and salvaging violins from the Holocaust. He rebuilds these violins, and many times they are played in orchestras around the world. He founded a program called Violins of Hope.

When I visited Amnon’s workshop in Israel, he told me stories about people getting rid of their instruments because of the memories. The instruments also started coming to him after his work became known. The interesting thing about those violins is that if you’re a single musician using this one instrument repeatedly, it starts to reflect your unique sound. For example, if a player picked up her instrument 30 years later, the grooves are borne down in this particular way on the instrument. It’s like bringing back the voice of the lost player.

Do you play the violin?

I don’t, but my father played every day. I grew up listening to him. I think my father’s violin playing helped him to connect to his Jewish roots. I also observed the transportive power of music through him. During my research, I also connected with an incredible violinist who worked with me to understand what pieces Shira would play and how she would practice. He wrote me emails about what it would feel like to hold the violin—the amount of sweat that would be on Shira’s fingers and hands, and how she would slide her fingers across the fingerboard.

Róza makes the heart-wrenching decision to send Shira to a convent to save the girl’s life. Tell us about that.

I wanted to convey that the decision to save your child could entail a sense of guilt or [make you] think of the different ways you could have done things. In the novel, I purposely show children who made it to the family camp in the woods, and Róza saying, “I might have been able to keep Shira with me. Why didn’t I keep her with me?” But then a child can also die in that scenario. Nothing is safe.

Did you deliberately choose the color yellow for the titular bird, which is so associated with the Holocaust?

I know there’s a connection—maybe partly conscious and partly unconscious—to the yellow stars the Jews had to wear on their clothing during the Holocaust. But I also connect the color yellow to the stars in the sky. In the end, the story of a girl and her yellow bird became part of the connective tissue between this mother and daughter, as was the love of music.

This interview has been edited and condensed.