The opening shot of “Hermana: The Untold Story of Ankara’s Jewish Community”—an award-winning film from Turkey—is an aerial view of what director Enver Arcak calls the “Albukrek House.” Arcak is in Boston for the film’s screening at the 17th Annual Boston Turkish Film Festival, running through April 1 at the Museum of Fine Arts. “Hermana” is a 28-minute documentary that concisely relates the rich history of Ankara’s Sephardic Jewish population.

My interest in the film is personal. My grandfather, Jacobo Alboukrek (the “o” was added to the name when he immigrated to Cuba), was born and raised in Ankara until he became a bar mitzvah. His story in Turkey is a mix of Jewish history and family lore. He used to recount that his family fled to Havana after he witnessed a Turkish soldier murder an Armenian man circa 1918. My grandfather said his father reasoned that if the Armenians were being killed, the Jews were next. Soon after that, my Albukrek family was on a ship heading west. Happenstance had it that it was going to Cuba, which was all the better for the Albukreks, who spoke Ladino and could easily pick up modern Spanish.

I tell my grandfather’s story to Arcak, who says it’s plausible but points out that at the time there was virtually no anti-Semitism in Turkey. He tells me that the history of the Jewish community of Ankara can be traced back to the Roman times. Jews back then, he says, were called “Romaniots” and lived in Ankara and other parts of central Turkey. Centuries later, thousands of Sephardic Jews arrived in Turkey after their expulsion from Spain in 1492. Others, like my grandfather’s family, came a few generations later from Portugal and the Netherlands.

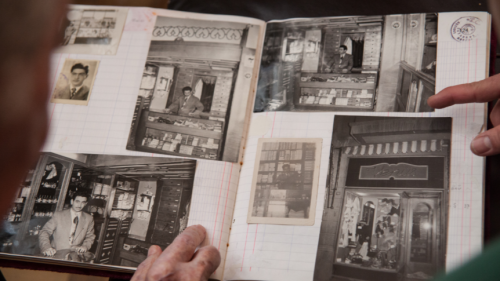

Ankara’s Jewish story is also one that is reflected in its stark numbers. In the 1930s, the community peaked at about 5,000. Arcak says today that number is fewer than 30 people, and most of them are not native to Ankara. Their ranks include diplomats and U.N. officials. Arcak, who is not Jewish, was born and raised in Ankara. He’s a historian of archeology who dedicated himself to documenting this disappearing remnant community. “I started researching ‘Hermana’ seven years ago, following the immigration of Ankara’s Jews to the United States, Israel and Istanbul,” he says. “I interviewed hundreds of people to compile an oral history and a visual archive of letters, diaries and religious papers. It’s a deep subject and this documentary is the result of putting all those things together.”

Arcak says the community began to dwindle noticeably in 1942 after the Turkish government placed a wealth tax on its Jews, Armenians and Greeks. The fee was exorbitant and few people, including Jewish communities throughout Turkey, could afford to pay it. Caught in an economic boondoggle, Arcak says that after World War II many Turkish Jews went to the new State of Israel. Turkey was neutral during the war and the community was saved from the Nazis.

Arcak’s sepia-tinged history picks up again in the 1960s and ‘70s. By then Ankara’s Jewish population barely numbered 600 Jews. Nevertheless, “Hermana” shows it to be a lively community in words and pictures—a community that celebrated milestones and made sure to educate its youth in Judaism. However, by 1968 the number of Jews had steadily declined. According to Arcak, Ankara’s last rabbi immigrated to Israel in the 1980s. He says that in the wake of a military coup in 1980, the community sent most of its Torah scrolls to Israel for safekeeping. According to Turkish Jews in Israel, those scrolls went missing and have never been recovered.

Arcak interviewed over 50 Jews from Ankara for the documentary, most of whom have relocated to Israel. There are also the recollections of Jews who live in Istanbul, the largest Jewish community in Turkey, estimated to be upwards of 17,000 people. Just over a thousand Jews still live in Izmir. But Arcak says those communities are also shrinking. The failed coup of 2016 sent more Jews packing to Israel. Of those who remained, many obtained Spanish and Portuguese citizenship after those countries passed legislation offering citizenship to the descendants of Jews who were expelled during the Inquisition.

As for my personal quest to find the Albukreks of Ankara, Arcak says there’s a member of the Albukrek family who still lives in Ankara and has been assembling a family tree. I’m anxious to see if Jacobo and his forebears are on it.

For more information about the “Hermana” screening on April 1 through the 17th Annual Boston Turkish Film Festival, please click here.