This summer, Emerson College turned to public artist Julia Csekö to impart a message decrying the racism and antisemitism of graffiti found in a stairwell close to the college’s Boston campus. Csekö had previously created a mural for the college in 2014, presenting the words of philosopher and communications guru Marshal McLuhan.

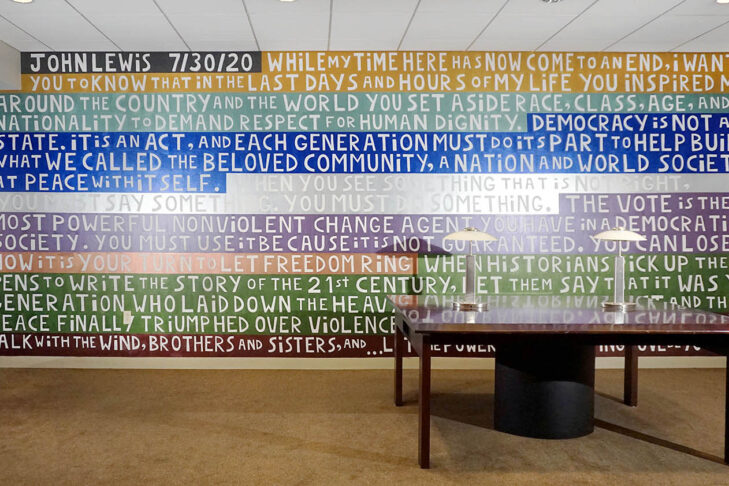

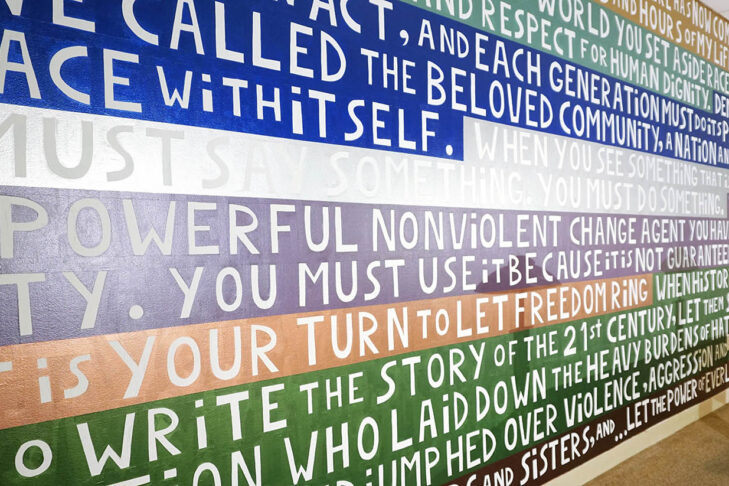

At the request of Leonie Bradbury, a professor of contemporary art theory and the college’s curator-in-residence, and student representatives, Csekö again looked for the right words, this time to bring healing to the campus. With guidance from Bradbury and her student committee, Csekö focused on Congressman John Lewis’s posthumous op-ed printed in the July 30, 2020, edition of The New York Times. Lewis wrote the essay to lift up the message of the Black Lives Matter movement, and the piece was read at his funeral.

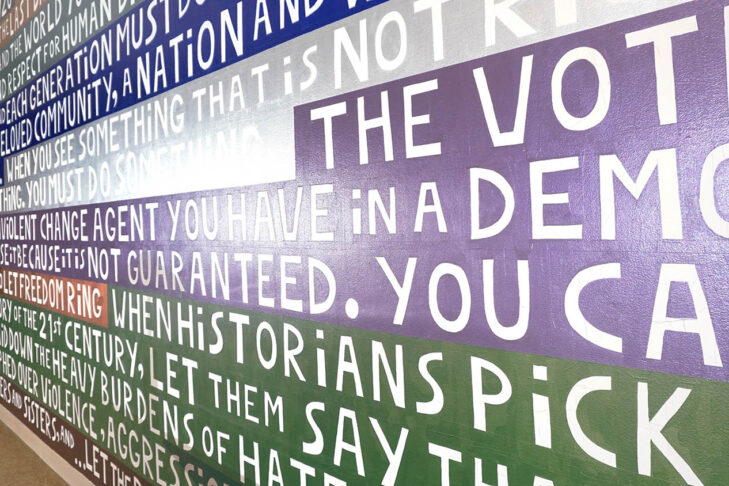

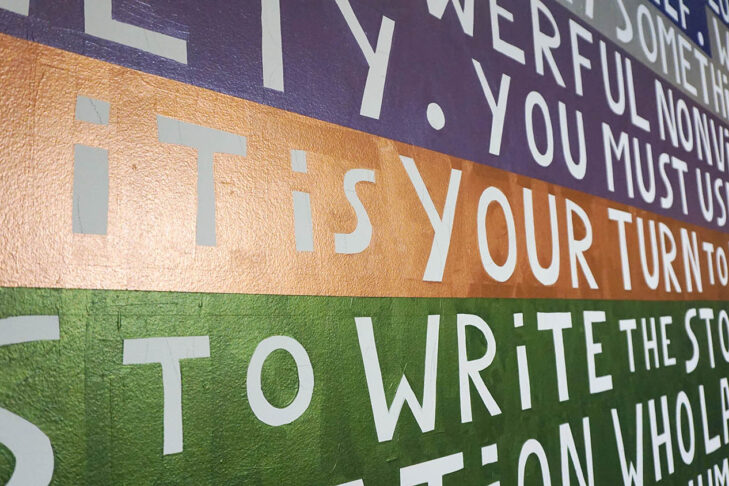

Writing about memorializing Lewis’s words in her mural, Csekö noted: “Lewis urges us to continue to exercise our rights and duties as citizens. To participate, to unite, and to vote, because in his own words, ‘democracy is not a state, it is an act,’ and the right to vote is not a guarantee; it needs to be upheld as the clearest sign of a functioning democracy. In honor and remembrance of all those who were lost to the horrors of the Holocaust, and to the horrors of slavery. In honor and acknowledgement of all of those who still suffer prejudice, bigotry and violence, be it for their religious faith, their culture, the color of their skin or their sexuality. Let John Lewis continuously encourage us to unite and build a better future.”

Csekö recently spoke to JewishBoston about her work as a multi-disciplinary artist and the process of pairing word and image to impart crucial messages.

What genres do you work in?

I am a multi-disciplinary artist and work as a sculptor, painter and performer. My paintings are meant to be public art. They are life-size so that they envelop the viewer. I have a public mural currently on view at Winter Place. It’s an alleyway used as a shortcut. The Boston Downtown Improvement District commissioned the project. They were looking for new art to install in the Literary District and knew I worked with the written word.

We brainstormed about which local writers to focus on. I chose Margaret Fuller, who was an early feminist, and there’s an excerpt of her text in the work. Then there are Edward Bellamy’s words; Bellamy wrote very funny utopian socialist science fiction. I also wanted to include the present, so I reached out to Eddie Maisonet, a spoken word artist. They are a queer, trans, Puerto Rican person of color, and I thought their words needed to be in the piece.

Who commissioned this new public art at Emerson?

This mural was part of the late Joe Ketner’s legacy. He taught a class at Emerson where the students’ final project was to create a show. They went to universities and local art schools and picked artists. That was my first interaction in 2004 with Emerson, and I created a mural that was eventually erased. But then in 2014, Emerson asked me to create something at the entrance of the Walker Building that would usher students into the space. They gave me this huge wall that was more than 20 feet and told me I could do anything I wanted.

I was reading Marshall McLuhan and thought about his aphorisms. They were quick and colorful. It happened that Emerson had a relationship with the McLuhan Foundation. It was a mural that brightened up a dark entrance. The mural had neon and other vivid colors. It was up for two years before the space was renovated. Before tearing it down, they saved chunks of the wall, which I love.

How did you and Leonie Bradbury come to collaborate on the John Lewis mural?

Leonie Bradbury took over Joe’s role and has preserved his vision. She and I communicated after antisemitic graffiti was found on a stairwell in Piano Row near an Emerson building. Emerson’s first reaction was to reach out to the student body to consult with them and make them feel responsible for their space. The students wanted a mural that responded to the incident. John Lewis had just died, and I wanted to use excerpts from his final letter.

How did you pick the sections of the letter you wanted to highlight in the mural?

I read the letter a few times. It has so much information and is so reflective of our current time. Leonie then created a student advisory board to help select the text. The feeling was also to include a Jewish author, so I went to Hannah Arendt. I wanted to work with her ideas about totalitarianism in her book, “The Origins of Totalitarianism.” That book is an important lesson on how we got here and how worse things can get. The first sketch I created was with her work.

But one of the issues we had was that everybody is exhausted. There’s quarantine fatigue, isolation fatigue, political fatigue, brutality fatigue and negativity fatigue. The student committee wanted a message that was positive and uplifting. The text I was working with denounced where we are instead of saying, “We could go other places.” I understood why the Arendt text was too dark to live in a space for students that are our future. It wears you down to have this dark, powerful message screaming at you in giant letters.

Did Leonie and her student committee pick John Lewis’s text specifically for its optimism?

They did. Capturing that spirit of optimism, John Lewis says, “Democracy is not a state, it’s an act.” Upon reading those words, a switch flipped for me and it was so amazing and so right for the space.

This interview has been edited and condensed.