Have you ever wanted to know what people talk about in therapy? Even outwardly serene, happy people? Here’s your chance to find out.

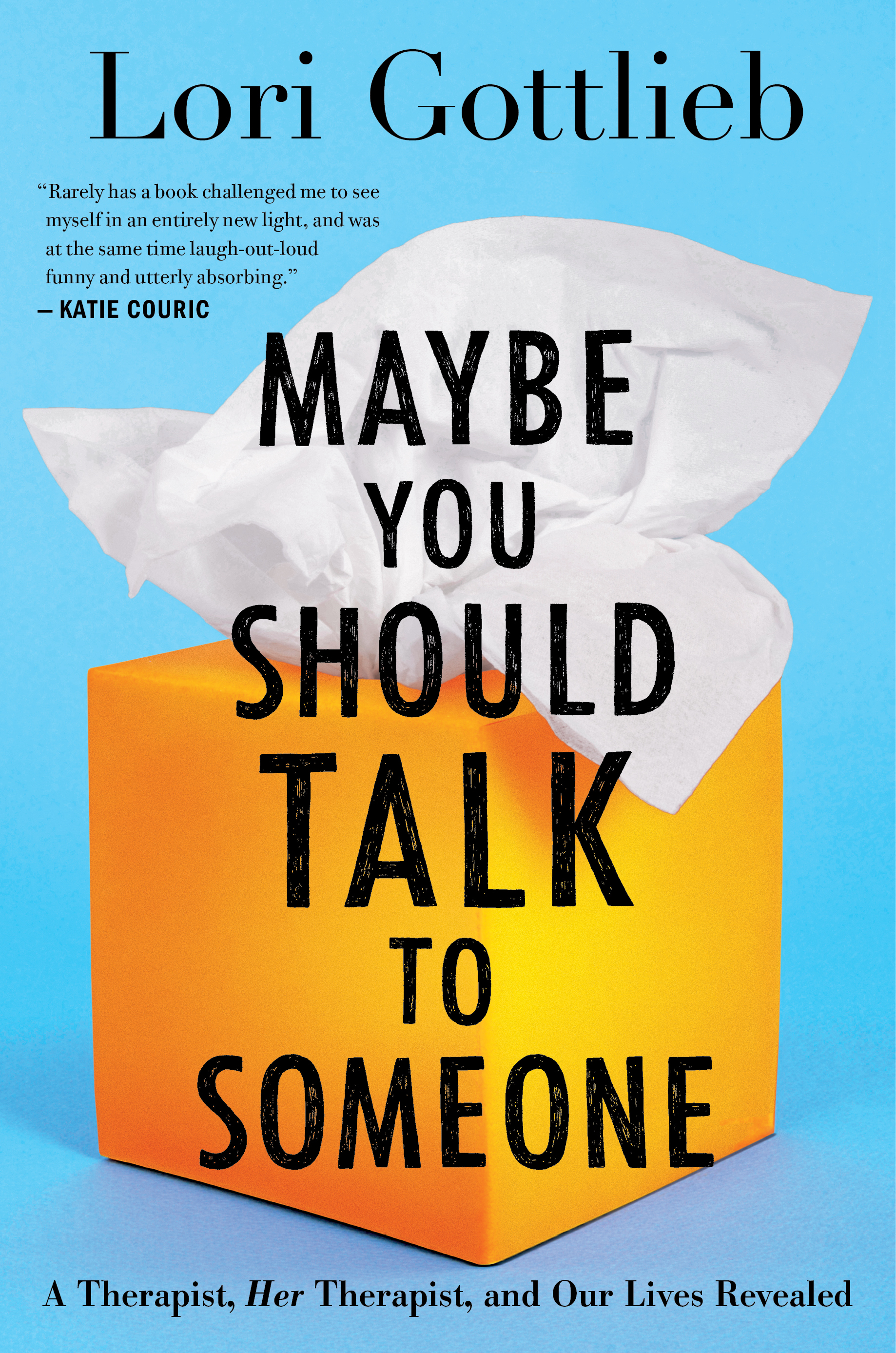

Lori Gottlieb shares all this in her newest book, “Maybe You Should Talk to Someone: A Therapist, Her Therapist, and Our Lives Revealed.” She takes readers behind closed doors into her own inner life, as well as those of her patients—a self-absorbed Hollywood producer, a newlywed diagnosed with a terminal illness, a senior citizen threatening to end her life on her birthday and a 20-something who can’t stop hooking up with the wrong guys. These vignettes get at what it means to be human, what it means to struggle and the individual yet universal quest for some kind of salvation. It’s now being developed into an ABC TV series with Eva Longoria.

The New York Times bestselling author and Atlantic columnist opened up to JewishBoston about what really happens inside a therapist’s office: What leads some people to therapy but not others? How can we be happier? How do therapists deal with unlikeable patients? (They’re human, too, after all.) And, really, what’s up with people who appear to have charmed lives?

If you had to generalize and name a common thread among your patients, what is it? Is there a universal human affliction, longing or need that leads people into therapy?

People come in for all kinds of reasons. A breakup, a death, a job loss, an adjustment—to parenthood, marriage—or something less concrete, like a feeling of stuckness, or the sense that something just feels “off.”

But I think at the end of the day, we all deal with the same questions: How can I love and be loved? What’s getting in my way? Why do I find myself in this pattern over and over again? How do I move forward from loss? In the book I write about the fears people have: We are afraid of being hurt. We are afraid of being humiliated. We are afraid of failure and we are afraid of success. We are afraid of being alone and we are afraid of connection. We are afraid to listen to what our hearts are telling us. We are afraid of being unhappy and we are afraid of being too happy. We are afraid of bad health and good fortune. We are afraid of our envy and of having too much. We are afraid to have hope for things that we might not get. We are afraid of change and we are afraid of not changing. We are afraid of something happening to our kids, our jobs. We are afraid of not having control and afraid of our own power. We are afraid of how briefly we are alive and how long we will be dead. We are afraid that after we die, we won’t have mattered. We are afraid of being responsible for our own lives. We talk about all of this in therapy—these are the common threads.

What’s up with people who seem to have charmed lives? How do they do it: tons of friends, busy social lives, happy marriages? Are there really some people like this, or is it a front? Or does it just make us feel better to assume it’s a front?

As a therapist, I often see people comparing their lives to others, and one reason I chose to bring readers into the therapy room with me is to show how similar we all are, no matter what our lives look like on the outside. I once heard someone say that comparison does one of two things: it makes us feel superior, or it makes us feel inferior. And both positions leave us isolated. Comparison is especially hard to avoid in this era of curated Instagram and Facebook posts, but like women’s magazines, those images aren’t real, or at least what we think they are. A colleague jokingly said her theory was that people who suddenly start posting every day about their wonderful marriages announce three months later that they’re splitting up. Sometimes the veneer is a defense, and most of what we’re comparing ourselves to isn’t the full story. We all struggle; nobody is immune to it. But when we’re struggling, we forget this, and for that reason, I think comparison is dangerous. It makes us feel isolated in our experience, even though we’re all more the same than we are different at our core.

How do you deal with being a therapist if you might have the very same issues some of your patients come to you about? Do you compartmentalize? Pop an Ativan before a session? How do you take yourself out of the appointment?

Hopefully we’ve come to understand our issues in a way our patients might not have yet, so even if we haven’t resolved them completely, we have a clearer sense of them. But we do have our blind spots, just like our patients. The difference is that we have the vantage point of not living our patients’ lives, so we have a perspective on their lives that’s easier to see as an outside observer. We’re there to hold up a mirror to them, to say, “Here are the ways you might be shooting yourself in the foot over and over.” And if we can see it even better because we’ve experienced some version of that, then of course we won’t be talking about that in the session, but we’ll certainly use it to help the person in front of us.

What happens if you actually loathe your patient? Do therapists do that? Can you fire a patient?

During my training, a supervisor once said, “There’s something likable in everyone. It’s your job to find it.” And I thought, “Yeah, well, that can’t be true for everyone!” But that’s actually been my experience. You can’t get to know somebody deeply, to learn about their more tender places, their childhoods, their vulnerabilities, their secrets, and not come to feel genuine affection for them, even if you wouldn’t necessarily connect as friends in another context.

What about seeing a patient in public? Do you play coy? Avoid them? Dive behind a potted plant?

There’s a chapter in the book called “Embarrassing Public Encounters,” in which you see what happens when I do run into patients outside the office. I won’t say “hi” to patients unless they address me first, because they may not want to explain to the person they’re with that I’m their therapist. But also, it’s jarring for people to run into their therapists out in the world, in the way that kids find it jarring to run into their teacher in shorts and a T-shirt, arm-in-arm with their spouse at Best Buy. “Wait, Mrs. Jones has a life outside of school?” But we’re just people living our lives. Once, a colleague of mine who’s a respected child psychologist was in the bakery when her 4-year-old had a meltdown about not getting another cookie, culminating with the ear-piercing proclamation “You’re the worst mom ever!” while her 6-year-old patient and her mother looked on, aghast. The most embarrassing thing that happened to me was when I ran into a former patient in the bra section of a department store after the clerk announced loudly over the dressing-room door, “Good news, ma’am! I was able to find the Miracle Bra in the 34A.”

We all know people who have been in therapy for years. Is there ever an end date? Should patients set a time limit? Do therapists, if they think the person is just going in circles?

Progress is always being assessed, because our goal from day one is to make it so that you don’t need us anymore. It’s a terrible business model, and there might be a few bad apples out there, but I don’t know any therapists who want to see someone who shouldn’t be there. If the patient isn’t progressing, and we aren’t able to help, we want to get the patient to someone who can. Or maybe the patient isn’t truly ready for change, and maybe they should come back when they’re ready. In the book I talk about a patient I couldn’t seem to help, and I did end our work together because I didn’t want to waste her time. But that’s rare. More often, we assess progress with our patients and openly talk about when might make sense for them to stop.

With the exception of life-or-death or abuse scenarios, are people’s problems ever as big as they’re making them out to be?

I like to say that there’s no hierarchy of pain, and I’m referring to the ways in which people rank their pain. In the book there’s a young woman I’m treating, a newlywed with cancer, and at one point, after she seems to be tumor-free in the aftermath of an experimental treatment, she and her husband find themselves less irritated by a pipe bursting in the kitchen or a traffic jam or the other daily annoyances we all deal with. “At least I don’t have cancer,” she’d say, but that’s also a phrase that healthy people use to minimize their own suffering. But, in fact, there’s no hierarchy of pain. Suffering shouldn’t be ranked, because pain is not a contest. Spouses often forget this, upping the ante on their suffering—”I had the kids all day. My job is more demanding than yours. I’m lonelier than you are.” Whose pain wins—or loses?

But pain is pain. I’d done this myself, too, apologizing to my own therapist, embarrassed that I was making such a big deal about a breakup but not a divorce. But Wendell told me that by diminishing my problems, I was judging myself and everyone else whose problems I had placed lower down on the hierarchy of pain. You can’t get through your pain by diminishing it, he reminded me. You get through your pain by accepting it and figuring out what to do with it. You can’t change what you’re denying or minimizing. And, of course, often what seem like trivial worries are manifestations of deeper ones.

I think that because we rank pain, people don’t place enough value on their emotional health. If you were having chest pain, you probably wouldn’t wait until you had a massive heart attack to seek help. You’d get it checked it out. But if people are experiencing emotional pain, they tend to say, “What right do I have to feel sad? I have a loving family and a job that pays the bills.” So they pretend their pain isn’t there, but even if you try to suppress those feelings, they’re still there, and they just get bigger. They need air, and eventually, they’ll find a way out. They come out in unconscious behaviors, in an inability to sit still, in a mind that hungers for the next distraction, in a lack of appetite or a struggle to control one’s appetite, in a short-temperedness or self-sabotage. So many of our destructive behaviors take root in an emotional void, an emptiness that calls out for something to fill it. Feeling less doesn’t mean feeling better. It serves no one to rank our own or other people’s struggles.

Does life get easier as we get older, do you think? Do younger people seem more mired in their “issues” than older ones?

In some ways it does. We tend to know ourselves better and care less about things that we wasted emotional energy on when we were younger. But as we get older, more has happened that we can’t go back and change. So I think we have to be intentional about our lives at any age, and that’s an area in which therapy can be very effective. My 69-year-old patient in the book is a perfect example of how it’s never too late to make even significant changes late in life. But you have to be ready, and you have to be intentional about it.

What’s the secret to mental serenity? This is hard to answer, but if you had to take a stab, what sort of outlook, thought process, practice, habit or bit of knowledge could lead people to feeling better?

If you want to feel more peaceful, be kinder to yourself. Most of us don’t realize that we talk to ourselves more than we’ll talk to any other person over the course of our lives, but our words aren’t always kind or true or helpful—or even respectful. Most of what we say to ourselves we’d never say to people we love or care about, like our friends or children. In therapy, we learn to pay close attention to those voices in our heads so that we can learn a better way—kinder, more honest, more helpful—to communicate with ourselves. Of course, that doesn’t mean to stop taking responsibility for your actions. It just means to change your approach. There is a difference between self-blame and self-responsibility, which is a corollary to something Jack Kornfield said: “A second quality of mature spirituality is kindness. It is based on a fundamental notion of self-acceptance.”

In therapy, we aim for self-compassion—am I human?—versus self-esteem—a judgment: am I good or bad? And when we stop self-flagellating and shaming ourselves, we can look at what we want to do differently and take responsibility for how we live our lives. A bonus to being kind to ourselves is that it makes us more compassionate people to others as well.

Lori Gottlieb will visit Brookline Booksmith on April 5 at 7 p.m. to discuss her book with Harvard professor and social psychologist Amy Cuddy. Her book is out in hardcover on April 2.