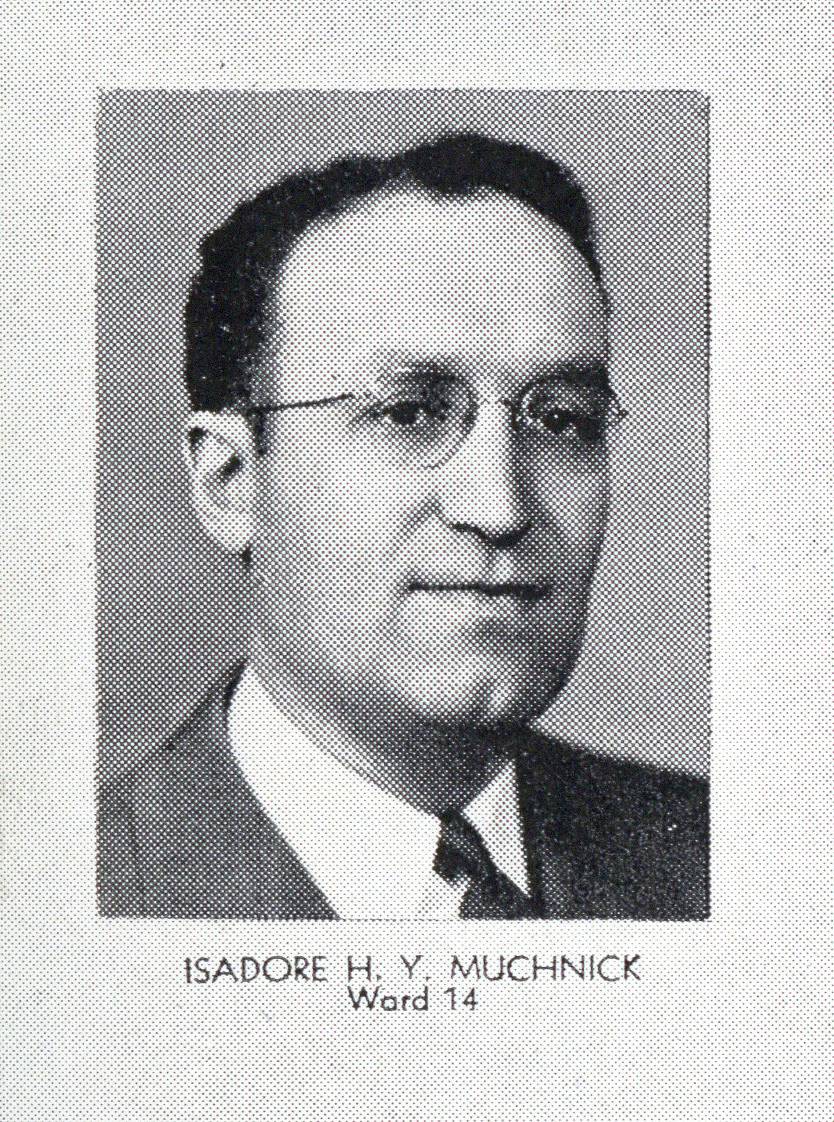

The Red Sox are an all-white team, businesses are closed on Sunday, and Dorchester is a Jewish neighborhood. It was 75 years ago. Boston’s old Ward 14, site of the legendary G&G Delicatessen (the locus of erev Election Day rallies before the Jewish migration to Brookline, Newton, and other suburbs), was represented by City Councilor Isadore H.Y. Muchnick.

Muchnick, who pursued justice (as Deuteronomy put it), realized that he had leverage to bend the arc of the moral universe toward justice (as Martin Luther King later put it). Here’s Muchnick recounting his effort: “Back in ’44, I had been reading about the Red Sox being biased against Negroes. I was in the City Council at the time. So I made up my mind to do something about it,” Muchnick told The Boston Globe in 1959.

“The members of the City Council voted each year on whether to let the Braves and the Red Sox play Sunday ball. So in ’44, I made a motion in the council one day to ban Sunday ball in the two parks.” The Red Sox, the American League team, played then, as it does now, in Fenway Park. The Braves, then Boston’s National League team, played at Braves Field, which is now Boston University’s Nickerson Field.

In response to Muchnick’s motion, the general manager of the Red Sox, Eddie Collins, wrote to him that the team would be happy to have African American players—but none wanted to play in the major leagues because they made more money in the old Negro baseball leagues. Muchnick publicized the response. Wendell Smith, a writer for The Pittsburgh Courier, an African American newspaper, disputed the Red Sox’s contention.

“I let the thing rest that year. But the following year, I made the same motion—and I was going to get tough about it.” The Red Sox general manager responded with another letter, this one saying that the team would grant tryouts to African Americans. Muchnick contacted Smith and “told him to line up some ball players.”

On April 15, 1945, Muchnick went to Fenway Park. Collins, the Red Sox manager, and Smith, the Pittsburgh Courier writer, were there. As Muchnick related, Collins said to him, “You are putting me on the spot, but I will go through with it. However, not a line is to appear in any paper—and no photographers are to be on any field. If there are any, the tryout is off.”

“We agreed”—which is why details only dribbled out until Muchnick told The Boston Globe what he remembered 14 years later.

The tryout was the next day, April 16, 1945. Opening day was the day after that. The three players were Jackie Robinson, who went on to integrate the modern major leagues two years later, Sam Jethroe, and Marvin Williams. “I’m telling you, you never saw anyone hit the wall the way Robinson did that day,” apparently referring to the Green Monster in left field—“Bang, bang, bang, he rattled it. The others didn’t do as well.”

“Joe Cronin—who was manager—was watching. When the workout ended, I remember going over to Cronin. He was struck on Robinson. He said to me, ‘If we had that guy on this club, we’d be a world beater.’”

Other people have recounted the tryouts differently. Someone probably yelled from the stands, “Get those [racial slur] off the field!” It may have been Tom Yawkey, the owner of the Red Sox. But these are Muchnick’s memories that The Boston Globe published 14 years later.

The Red Sox had the three sign applications. “With that accomplished,” Muchnick continued in 1959, “I called John Quinn of the Braves the next day. He said something to me about it being impossible for the Braves to look at the men if the Red Sox had already done so. That was a lot of bosh, and I told him so.”

But not enough was accomplished. The Red Sox were apparently going through the motions, which was more than the Braves did. Nothing came of the tryouts.

That is, nothing directly came of the tryouts for the three players and the Red Sox. Muchnick nudged baseball toward racial integration. And Muchnick and Robinson became friends.

In 1947, Robinson broke the so-called color line for the Brooklyn Dodgers. At games, Jews cried out for him, “Yankel, Yankel”—Yiddish for “Jackie.” The Boston Braves integrated three years later in 1950 by signing Sam Jethroe. (The Braves left Boston in 1952. They became the Milwaukee Braves and are now the Atlanta Braves.) Williams, the third African American who tried out in Fenway Park in April 1945, never made it to the major leagues. The Boston Red Sox became the last major league team with an African American player—Pumpsie Green in 1959.

Slavery is America’s founding shame. One of Boston’s lasting shames, its shondah, is that the Red Sox were the last team to integrate.

On the night of his tryout in 1945, Robinson went to Dorchester for dinner at the home of Muchnick and his wife, Ann, at 9 Powelton Road. Later, when his Dodgers played the Braves in Boston, Robinson regularly returned to Muchnick’s home, as Howard Bryant reported In his book, “Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston.” Robinson once spoke at Muchnick’s synagogue at a father-and-son breakfast; Robinson came with one of his sons.

The 75th anniversary of the tryouts on April 16, 1945, came and went during the second month of the coronavirus pandemic and shutdown. Jewish cemeteries were generally closed, except for burials. With a delayed opening to a shortened baseball season, we can still mark Muchnick’s effort that led to the tryouts on the day before opening day three-quarters of a century ago. And we can do so during the national reckoning on race impelled by the tragic killing of George Floyd on May 25, 2020.

On July 23, the day before the Red Sox were scheduled to open the 2020 season in Fenway Park, and, with Jewish cemeteries open again for non-funeral visits, I went to Muchnick’s gravesite.

Isadore Harry Yaver Muchnick was born in Boston’s old West End on Jan. 11, 1908. He attended Boston Latin, Harvard College, and Harvard Law School. In 1942, Izzy, as he was called, won a special election to the Boston City Council. In 1947, he was elected to the School Committee and served through 1953.

A practicing lawyer, he died too young of a heart attack on Sept. 15, 1963, at age 55. By then, he had moved from the old Dorchester neighborhood to West Roxbury. He is buried in Adath Jeshurun Cemetery in West Roxbury.

I knew the section number where Muchnick, his wife, and his parents are buried (the Jewish Cemetery Association of Massachusetts had told me), but when I got to the cemetery, I saw no section numbers marked. The map I held showed the location of the odd-numbered and even-numbered sections without giving section numbers, so that cut my search in half. The cemetery is not vast.

I took off my suit jacket and started walking down rows of graves, looking for Muchnick and his kin. The sun beat down on my straw hat. A large bird soared overhead. A breeze lifted my baseball tie. No one else was there.

After a half an hour, I found a large marker carved “MUCHNICK.” In front of it were four ground-level plaques for each member of the Muchnick family. I put a rock on top of the family marker. I said El Malei Rachamim, a prayer for the dead, out loud through my mask. “God of compassion,” I read in Hebrew, “remember all his worthy deeds in the land of the living.”

Isadore’s plaque remembers him as a “Beloved Husband and Father.” Muchnick’s son and daughter are not living. He may have descendants in Israel, David Ellis, an experienced Jewish genealogy researcher, has told me.

I walked back to my car, perspiration streaming down my cheeks under my mask.

A memorial plaque for Isadore Muchnick hangs in the sanctuary of Temple Emeth in Chestnut Hill. Zikhrono livrakha. May his memory be for a blessing.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE