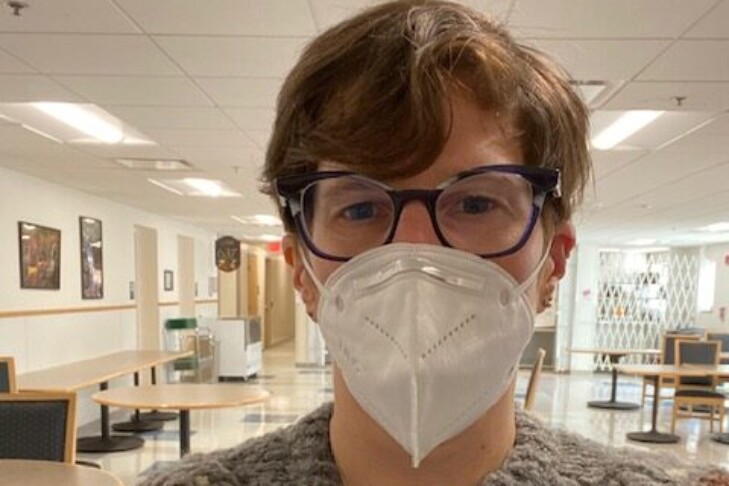

From the pandemic’s start, Dr. Pamela Adelstein pivoted quickly and donned full personal protective equipment to treat COVID-19 patients at her clinic in Dorchester. As she thought about ways to keep her patients healthy and keep people in her Jewish community safe, she turned to writing.

Adelstein has been interested in writing narrative medicine since her residency days. When the pandemic hit, she was moved to chronicle her encounters with patients in an underserved population and dispense advice on staying virus-free. In these past months of the pandemic, she has published essays in Cognoscenti, and her Facebook postings on COVID-19 safety are widely shared.

Adelstein recently spoke to JewishBoston about her experiences as a front-line physician, how Judaism informs her practice of medicine and moving moments with her patients.

Tell us about your medical practice.

I practice family medicine in Codman Square in Dorchester and cover medical issues from “womb to tomb,” as they say. I do everything from prenatal care, contraception and well-woman care all the way through end-of-life work. I’m also trained in medical acupuncture and mind-body medicine work with individuals and groups.

Who are your patients?

Many of my patients speak Spanish as their first language and represent a diverse Latinx population. Most of them are also people of color. Eighty-five to 90% of my patients have some public type of insurance. I see a lot of trauma, which includes the effects of post-incarceration, as well as the ways incarceration affects families. I also have patients from Vietnam, Africa and the Caribbean islands.

What was it like to transition to being a pandemic doctor?

Being a pandemic doctor was harder than residency; it’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done. During my residency, I was very conscious of not wanting to disappear as a human being. But when the pandemic hit, it was full speed ahead. As a community health center, we were a testing site, and we never closed. This pandemic was something we had never seen before and we had to figure it out with no time or experience. We essentially made it up as we went along. A lot of medical care was placed on hold, including elective surgery. We also built tents to triage patients for both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 urgent care. I, and many other providers, spent hours in the tent in PPE. We covered our arms in giant rubber gloves to swab people, and sometimes the weather affected care.

You have fortunately not had COVID-19. How have you protected yourself?

I wear scrubs to work and am covered in PPE. When I come home, I strip by the door, immediately get into the shower and throw the clothes I’ve worn that day in the wash. I have shoes that I only wear to work. In the early days of the pandemic, when we were being advised to wipe down our groceries, no one drove my car.

How did you start writing about COVID-19?

Narrative medicine and writing for doctors have been talked about for a long time to mitigate burnout. Burnout in medicine is something I read a lot about and have worked on a lot with providers. I’ve been writing for a while, and in that time I took some workshops. I did my residency at UMass, which has a narrative medicine newsletter.

I began writing in earnest when I read debates about wearing masks. When I heard about people attending Shabbat dinners and not taking enough precautions, I thought, “I have to write this down.” I wanted to report what was happening in some communities. My first Cognoscenti piece was based on a post I wrote for my Newton Center minyan. I was also moved to write about racial disparities and other topics related to COVID-19. People were very encouraging, so I’ve kept writing.

How does Judaism inform your work?

The most important lesson I take from my Judaism is to be kind. I tell my residents to do one thing a visit that moves a patient forward and to give them some love at every visit. Doing these kindnesses leads into tikkun olam. Health is the basis of so many things. I also think a lot about housing and food, and the privilege of having the company of others. That’s what we have in Judaism, and in so many ways it gives us purpose, a community and a system of ethics and morals. Many of my patients are religious. I’ve found commonalities with them in our belief in a higher power or our belief in humanity, even if we express it differently.

How do you counsel people to navigate the pandemic within their communities?

It is paramount to avoid close proximity to stop the spread of COVID-19. This includes things like singing or eating indoors. Zoom services or activities can connect you to spiritual practices. I think it is safe to be at an outdoor service attended by small groups of people. I mostly encourage people to see the long trajectory and to know that there is a lot of delayed gratification. It’s also important to keep up with the ongoing restrictions.

How do you handle burnout?

I wrote a short poem about that subject called “Burnout Meets Desperation”:

Message flashes: “Patient needs you to call.”

Me: No time or energy. Guilt.

I adore this kind, gentle patient. But I am tired.

I call, she answers, tentative, hopeful. Newly positive for COVID-19, she wants to hear my voice. I express concern, sympathy.

I hang up. Sadness weighs me down. My burnout meets her desperation.

What are some of the moving moments you’ve had with your patients?

It’s very moving when I connect with my patients over our shared humanity. My patients continuously inspire me. They are so caring and optimistic. They make do with what they have while making it so much more. They always ask about me. Much of our staff is from the surrounding community, and they are so dedicated. It is a privilege to witness people’s lives and have them share so much of those lives with me.

This interview has been edited and condensed.