“Pumpkinflowers: A Soldier’s Story” by journalist Matti Friedman is a spare and graceful memoir about serving in the security zone on the Lebanon border in the early 2000s. Friedman previously won a host of honors for his first book, “The Aleppo Codex,” which included the 2014 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature.

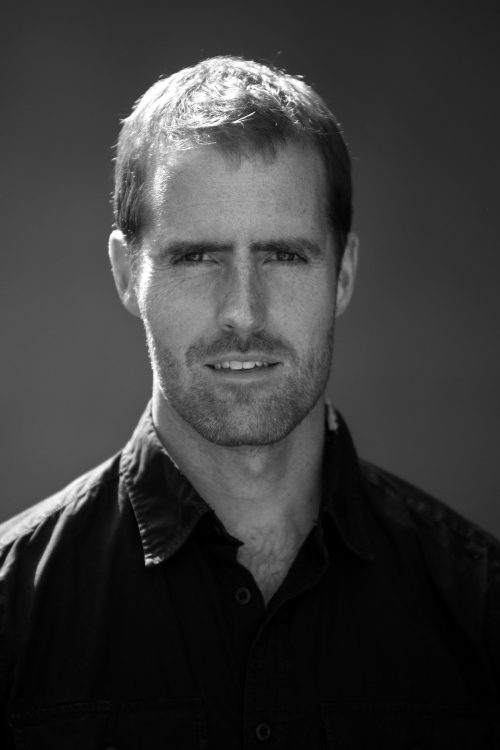

Born in Canada and now living in Jerusalem, Friedman first arrived in Israel to work on a kibbutz after graduating high school in Toronto. In a recent interview with JewishBoston, Friedman said that he had intended to return to North America after a year, but stayed on and was drafted into the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) from the kibbutz where he was working. “I got carried by the Israeli current,” he recalled.

That current deposited him at Dl’a’at (Hebrew for “pumpkin”), an army outpost set up on a small hilltop to patrol Israel’s security zone with Lebanon. It was there that Friedman and his fellow soldiers dealt with frequent nightly incursions from Hezbollah. Embracing memoir, he folds in the history of “the Pumpkin” and the men who served there in four sections. He introduces the Pumpkin as a place with a name that “now seems to hint at the kind of magic at work in the transformation of a bare hilltop into the scene of emotion and drama, and its sudden transformation back into a place of no importance at all.” The elegant sentence not only captures the arc of Friedman’s story, but also evokes emotional complexities that were intrinsic to serving at the Pumpkin.

Friedman chronicles the early years of military service at the Pumpkin through Avi Ofner’s story. Ofner, another 19-year-old from a different time and place, was drafted into the IDF in 1994. In conversation, Friedman noted: “I was looking for a way to tell the story of the years of the outpost before I arrived [in 1997]. Avi served there when the outpost became notorious. Beyond chronology, Avi turned out to be this fantastic character who was really heretical. He wrote beautifully about the army in that he could see himself from a distance. I felt very lucky to have found him.”

Like many incidents associated with the protracted Lebanon war, the outpost’s notoriety was briefly newsworthy in Israel. After three Hezbollah guerillas broke through the security zone in the fall of 1994 to plant a flag at the Pumpkin, the event was referred to as “the disgrace” in the media. Friedman describes the incident as Hezbollah’s Iwo Jima. But perhaps more significantly, the episode signaled the beginning of a new kind of warfare. “It was a sophisticated use of the media. Hezbollah manipulated perceptions,” said Friedman. “These guys understood very early on that a strong image, a shocking image, was a way to scramble people’s perceptions of what was going on and mainly who was winning. What really happened was that Hezbollah attacked the Pumpkin, stuck a flag in the ground and ran away. The footage looks like they’ve conquered the outpost.” Friedman observes that after the incident, Israel never recovered its image in the war of perception.

According to Friedman, the years in Lebanon are murky for many Israelis because there is no clear lesson to be drawn from them. “It’s hard to know what to do with 18 years of skirmishes in the bush,” he said. He noted that the Six-Day War was an unequivocal triumph, and although the narrative of the Yom Kippur War in 1973 encompasses the failures of Israel’s army brass, it was a war in which “soldiers with their grit turned the tide. And even though thousands of Israeli men shared the experience [of Lebanon], it doesn’t have a name, no official ribbon, no official monument. Not even an official death toll. It’s an intense personal memory for the people who were there and left with virtually no collective memory.” In the book, Friedman further comments, “It is easier to forget drawn-out affairs like ours than brief incidents of high drama, like a war lasting six days, just as a heart attack would stand out in memory more than a decade of chronic pain, though the chronic pain might be important to shaping who you are.”

The fourth act of “Pumpkinflowers” chronicles how the “chronic pain” Friedman experienced during his time in the security zone drove him to return to Lebanon proper in 2002 as a tourist once Israel had withdrawn. Despite the constant danger of being discovered as an Israeli citizen, he was determined to see those everyday places he saw from the outpost, including a gas station, hospital, ruined villas and a monastery. All at once forbidden geography becomes accessible to Friedman, and the irony that his parents live just 20 minutes away up the coast in northern Israel is never lost on him.

The hard lessons that Friedman learned from his military and civilian tours of Lebanon continue to teach him “how flimsy is the border between those two states, between Avi and me. This is the debt I owe [the Pumpkin], and the reason I am grateful for my time there.”