At 28, Abby Stein is one of the most visible trans activists in the world. She has forged a unique spiritual path that includes celebrating Judaism on her terms. Born in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn into one of the most gender-segregated communities in the world, the former Hasidic rabbi is also a 10th-generation descendant of the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism.

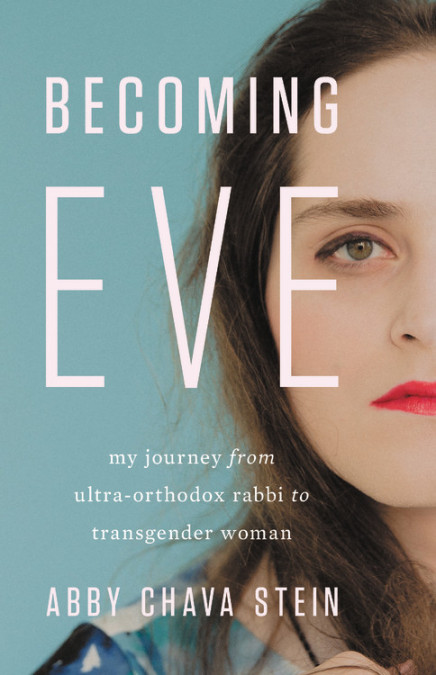

Stein delves into her earliest memories in her new memoir, “Becoming Eve: My Journey from Ultra-Orthodox Rabbi to Transgender Woman.” In lyrical prose, she presents a compelling, vivid picture of her earliest consciousness of a girl trapped in a boy’s body.

At 3 years old, when boys in ultra-Orthodox communities receive their first haircuts, Stein was distraught over parting with her long hair. She objected to the fact that her sisters didn’t have to cut their long locks. At age 4, her mother caught her poking at her genitals with a safety pin. “I was angry at ‘It’ for existing, and I wanted to make it feel my pain,” writes Stein.

Every morning Stein said the traditional Jewish prayer thanking God for not initially making her a woman. As Stein writes in the book, “But girls say this instead, and so did I: ‘Blessed are you, O Lord, our God, King of the Universe, who has made me according to His Will.’” Stein took those words to heart and was certain that God had intended for her to be a girl.

At the age of 19, Stein married and had a son within the year. As hard as she tried to ignore her gender dysphoria, she knew deep in her heart she had the soul of a woman. Stein, who did not know English at the time, accessed the internet on a smartphone she managed to find as she hid in a bathroom at a mall. The first thing she Googled was “boy turning into a girl.” She found a Hebrew-language Wikipedia page where she learned the word “transgender.” It was the first time she felt understood.

“Becoming Eve” is a standout in the genre of OTD memoirs—books that chronicle going “off the derech”—off the path—of a traditional Jewish life to live a secular life. Stein has done something more complex—she has written a book in which she reflects on the complexities and mysteries of gender and ultra-Orthodoxy, and how they are entwined. Her book is a triumph and her life is a marvel.

Stein recently spoke to JewishBoston about her book, activism and responsibility to other trans people coming out in religious communities of any faith.

What moved you to write your memoir at this juncture in your life?

Writing “Becoming Eve” was a spiritual experience. On a personal level, writing is therapeutic for me and has helped me make sense of my thoughts and feelings from a young age. I still have material I wrote in Yiddish when I was 5. When I started leaving the [Hasidic] community in 2012, I wrote a blog anonymously in Yiddish, and it was very powerful for people. I wrote a different blog in English when I came out. The response I got from people—many of whom I could tell were Hasidim because they either wrote in Yiddish or broken English—was they were feeling the same things I experienced. There had never been anyone Hasidic who came out as trans, and it showed me there was a need for me to write about it.

Your activism has been a lifeline to many people. Tell us about it.

There are two main parts to my activism—the public events, speeches, media and source sheets for gender and Judaism online. The private part consists of people reaching out to me. I have a dream to create a nonprofit to help more people. My story is one that impacts people regardless of background, gender or sexual identity. When I was dealing with addiction five years ago, the only way to live a full life was to come out as trans. I went sober in December 2016.

I get messages almost every day from people who want to leave their religious communities because they’re LGBTQ. They’re not just trans people, and they’re not only Jewish. People reach out to me about how my story has impacted them. I’m very aware that my story is more proclaimed and out there. If you see my before-and-after pictures, they are a bit more radical than the typical before-and-after pictures you see. It gives me an opportunity to raise awareness and talk to people.

Coming out to your father is a powerful scene in the book.

I wasn’t sure I wanted to have that conversation with my father. I was convinced, and ultimately, I was right, that my father would not accept me. I thought that when I came out publicly, he’d find out that way. But at that point, I had a relationship with my parents. My parents speak to their children every day, and I still talked to them every single day. As I was having the conversation with him, there was a part of me that thought maybe he might continue to talk to me by phone.

As we talked, we got to the point that he agreed trans people exist. But he said, “You need to have a person who has the kodesh baruch hoo—the holy spirit—to tell you if you’re trans. That’s the only way you’ll know.” At that moment, I knew there was nothing I could do to change him.

There are two kinds of transphobic and homophobic people—those who believe their religion forbids it and those whose culture doesn’t acknowledge it. You can actually talk with transphobic religious people. But changing the actual culture is harder. In terms of the community, I always joked that I wanted the Hasidim to become transphobic. At least it’s a recognition that we exist. Four years later, mission accomplished.

What does your Judaism look like now?

There’s a quote from an interview I did that captures the way I feel: “I always say I believe in Judaism more than I believe in God.” I don’t necessarily observe, but I celebrate. I light Shabbat candles every Friday night. I haven’t missed a week in five years. I always celebrate Shabbat in some form, whether it’s making dinner or going to a movie.

Initially, after I left the community, I needed something to ground me. People have been observing Judaism for thousands of years, and that’s a strong message. I have come to appreciate ritual. Today I embrace Judaism’s hopefulness. I embrace what I like and let go of what I don’t like. That is not just OK, but it’s beautiful. Some call this “treyf [unkosher] Judaism,” but I have come to appreciate that choosing is a positive thing. I founded a group called “Sacred Space.” It’s a safe space where women and non-binary people can come together and bring as much of their baggage as they want. The fact that they can leave the rest behind is a cause for celebration.

This interview has been edited and condensed.