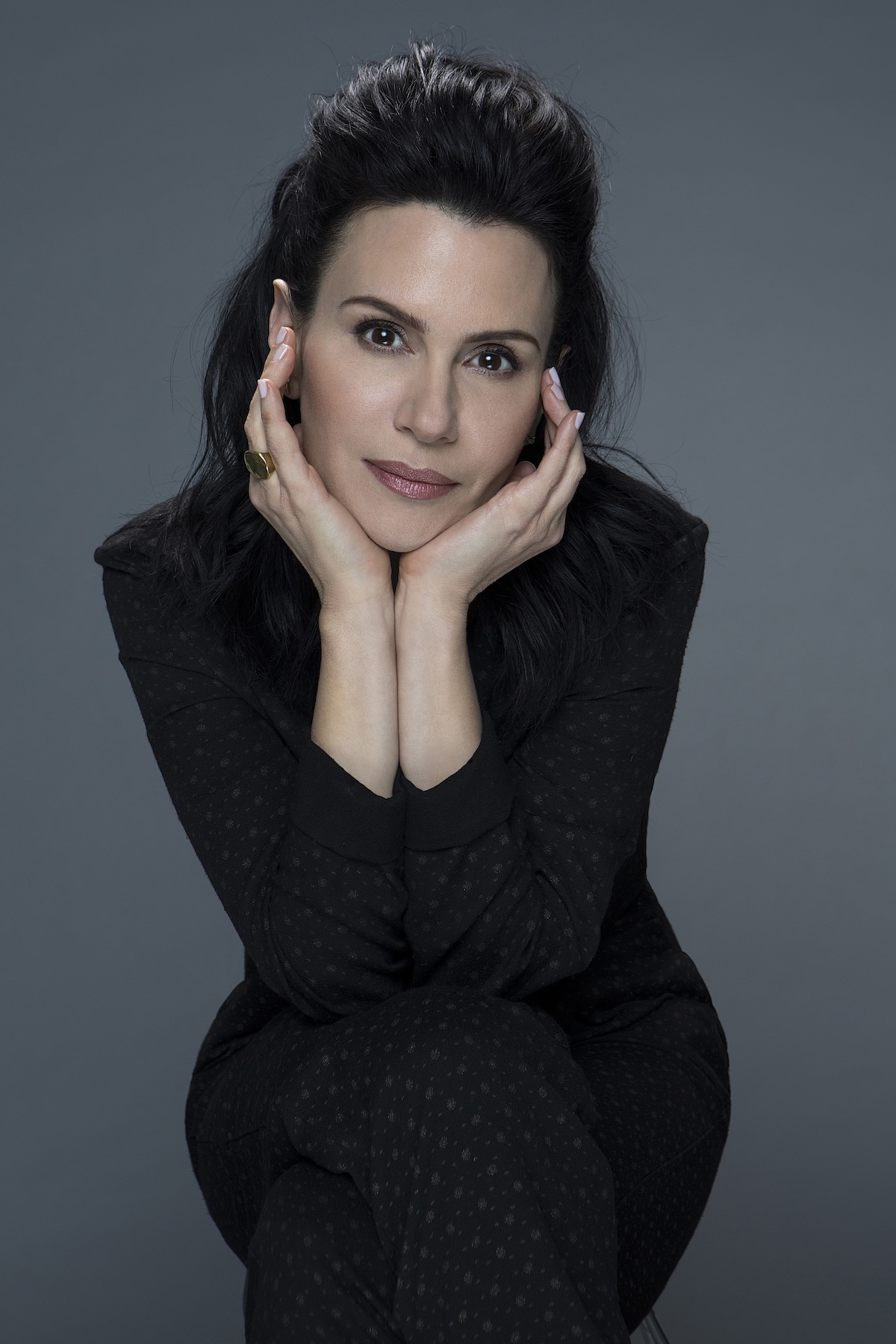

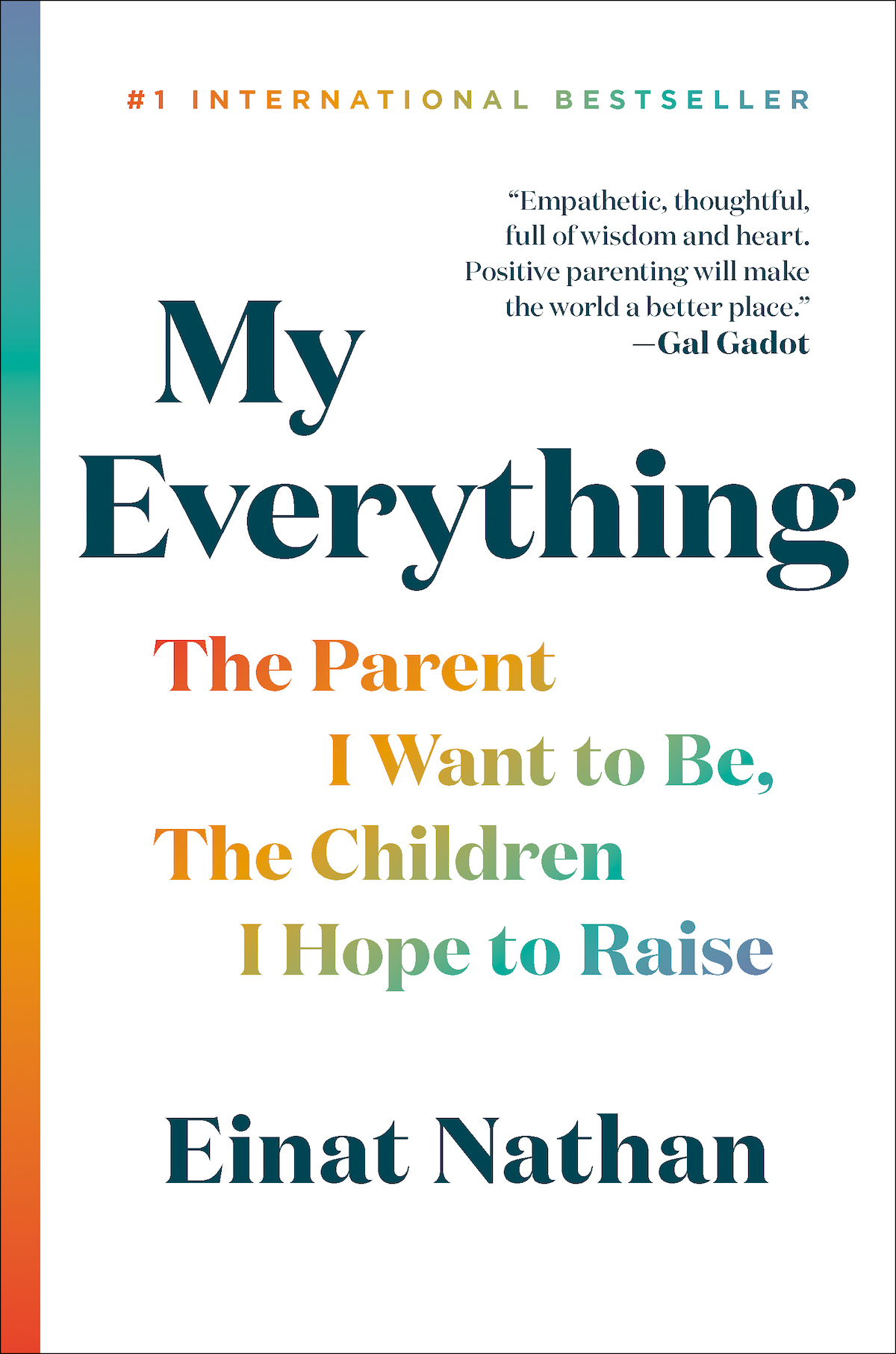

Tel Aviv-based author Einat Nathan is a noted parenting expert in Israel, and with five kids ranging in age from 8 to 21, she knows firsthand what she’s talking about. Her book, “My Everything: The Parent I Want to Be, The Children I Hope to Raise,” was a bestseller when it came out in Hebrew three years ago; this month, it was translated to English and released in the United States. She offered parenting advice to JewishBoston.

How is your book different from other parenting literature?

I think I’m kind of different [because] parents today are a bit tired of the know-it-all experts, ones that make them either feel guilty or feel like there’s something wrong with their children. And then there’s this whole world of mommy bloggers who do talk about the hardship of parenthood, but they’re not professionals. I think I found a way to interact with parents by talking personally about my own struggles and putting in my vulnerability, my secrets and my life with my imperfect children. And of course, adding the professional knowledge.

What struggles?

My firstborn was diagnosed with autism when he was 2-and-a-half years old, and it was a challenge, but now I can talk about it as a huge gift. I also struggled for years to be a mom. I went through stillbirth at the end of a pregnancy with twins at week 39 of the pregnancy, and we came back home empty-handed.

When we talk about vulnerabilities and struggles, what do you make of this mommy influencer culture? Hilaria Baldwin is one of the famous examples here in the U.S.

I think that, first of all, it’s a new world. We’re also raising children in this new world, and it has its advantages, meaning my daughters can definitely see a version of something that is less than perfect, struggling, not just the perfect yoga, skinny moms.

I think this world of bloggers gave an important platform to the fact that we are capable of sharing struggles. And I think that we, as a culture, are lonely as parents. We’ve lost the tribe we once had. We were supposed to raise our children in a tribe, not alone in our well-designed apartments and with our Instagram as a connection to the world. I think the tribe or the community was supposed to make space for struggling parents, or to even make knowledge accessible from the wise grandmother, and it’s a shame that the tribe is now commercialized.

Are parents too competitive with one another? Why?

Oh, wow. Where should I start? I think that, first of all, we live in a world where there is so much information, and mostly not organized. In the days of tribes, for example, moms were moms, that’s it. It’s like being a mom with four jobs, and now we think we can have it all. We juggle all these balls in the air, and we see a reflection of this lie that we can have it all. We can be fit, we can have an awesome career, we can have children who will echo our greatness. Children today became our business card, our Instagram profile, and they’re not supposed to be. And I think that’s the main issue. So on one hand, we’re struggling, looking for information. And on the other hand, a substitute of a tribe, A, is not good enough, and, B, I think it make us more lonely eventually.

I want to go through some ideas that are in your book. A couple of them really resonated for me. One thing that I think comes up a lot is that parents try to pave the way for their kids so they’ll succeed. Parents think each child is a special snowflake. They hate to see their children fail.

I think they are snowflakes in a way that we need to provide for each and every child of ours, that they’re special, that we see their traits and their super power, even if the outside world does not see it. But having said that, I think one of the biggest mistakes parents make is being a buffer between their children and life, their children and failure, their children and hardship, their children and pain, even their children and bad emotions. Toddlers are not allowed to have tantrums in public because there’s a parent who feels like there’s something wrong in that picture, and our children are supposed to be satisfied, happy, successful.

Life is school, and we need to let them encounter life. It’s like me having a wish that my child will learn how to ride a bike but wouldn’t fall or wouldn’t scratch her knees. I think we deprive them of such an important skill. I’m going to use an extreme term, but we make them sort of handicapped. It all begins with good intentions, but we are the spoiled ones because we lack the patience of seeing them struggling, or having them not satisfied, or failing or missing out. We think, by mistake, that having quiet children, or having no bad emotion, or having no struggles, means that we’ve made it, that we’re good parents. And that narrative dictates a certain parenthood that is spoiled.

When my oldest son got recruited for the army, I wrote him a letter, and the headline of the letter was “I Wish You a Hard Time”—not intolerable hard, but hard enough to ask for help and hard enough to get in touch with his inner power, and hard enough to meet interesting people who will help him, and hard enough for the processes that develop us.

Every parent faces the realization eventually that their way isn’t always the only way or the right way. Can you talk a bit about that?

I think it’s such a common and human mistake. We want to save him the journey. So let’s take a simple example. Being overweight is so hard, and children laughed at me when I was a child, and I want to spare my daughter the cycle of rejection, or even the hurtful self-image, so I decide to give her advice or to take her at age 7 to a dietician. And what I fail to acknowledge is that we’re not the same, that we are raising human beings that might look like us, even talk like us. They carry our genes, but they’re separate human beings.

So when my child comes home and says, “Nobody played with me,” I think, “Oh my god, his father was a misfit also. I can’t bear to raise such a child. I’m texting the kindergarten teacher just to find out if it’s really so.” Now, I’m really concentrating on my worry, on myself, on my pain. We are so good at giving advice. And I think that sometimes we fail at the listening process.

How do you think people can overcome this?

I don’t know how it is in the United States, but Israeli dads, for example, when they have a son who comes back from kindergarten and says, “John hit me,” the common Israeli dad would probably say, “When someone hits you, you should hit him back.” And the mom is horrified, and she says, “No, no, no. When someone hits, you need to go and tell the teacher. She will solve it.”

It’s an example of us skipping the process of: How did you feel? Were you insulted? Were you surprised? Did you fear? What did you think in that second? Were there any other children there? Just trying to be there with them. And we skip that because we’re concentrated on, “Oh my god, he’s going to be 16. He’s going to get bullied. He’s such a sensitive boy; we need to toughen him up.” That’s our inner logic, our experience, our agenda, our worries.

When our children share struggling or negative experiences that happened to them in the outside world, when they give us this gift, we are on a test. When we have teenage children, I think the first wish we have is that if something goes wrong, we’ll be their first phone call. But our test begins at 4 years old, coming to share something with us and having the experience that was worth sharing. So let’s talk about how we can create an experience for him in order for him to keep on sharing, in order for us to be even able to help him.

Parents need to understand that, for example, when they give certain advice, they are actually sending the same child back the day after with double jeopardy, because he’s going to encounter the same experience. And, now, if he can’t do exactly what I said he should do, he’s feeling like there’s something wrong with him. So it’s not just the situation he’s handling now—he’s handling the way he disappointed us; he’s handling the way he’s not capable of hitting John back. He’s handling another heavy backpack.

And children, by the way, have amazing ideas. But we have an agenda, and we jump in with our tips and recommendations. When they’re in school, we call the teacher, and we take care of everything and we post something. So now we have the likes of the other moms and we neglected them. We neglected their emotional needs.

What was the biggest lesson you had to learn as a mother?

Understanding that it’s not about fixing them, that it’s not about reprimanding them, that education is about relationships, and it’s about who we are and not what we talk about. It’s not about the best speeches in town that I can give a child. It’s about him watching me address the cashier in the supermarket, and the respect that my partner and I share for one another, even when we fight or we disagree. It’s about the space I can create within my family for all behaviors, for all traits, for all types of personalities to grow.

I think parenting is like the work of a farmer. If we have a plant that we grow in our backyard and we expected flowers, and there’s no flower, we never shout at the plant. We start checking the ground, and we start checking for bugs or for watering enough, or replacing a certain plant that is too close to it and making the possibility of light coming through. And I think sometimes we forget that we’re farmers, and we think of behaviors as something to be fixed.