Now in its 20th year, The Miriam Fund has been operating as a “philanthropic community committed to creating an equitable world that expands opportunities for women and girls.” An initiative of CJP, The Miriam Fund supports 17 organizations across Boston and Israel that exemplify its mission. The grantees are divided into three categories: secular organizations in Boston, Jewish organizations in Boston and organizations in Israel.

With its focus on women’s and girls’ issues, the fund is dedicated to championing social change as represented by organizations such as Hadassah-Brandeis Institute’s Boston Agunah Taskforce, PAIR Project and Turning the Tables, an organization in Haifa that assists women leaving prostitution. In this anniversary year, the fund has distributed over $300,000, doubling its financial impact over the past two decades. Its reach and influence were celebrated last week at an event featuring American Israeli author and social justice activist Talia Carner.

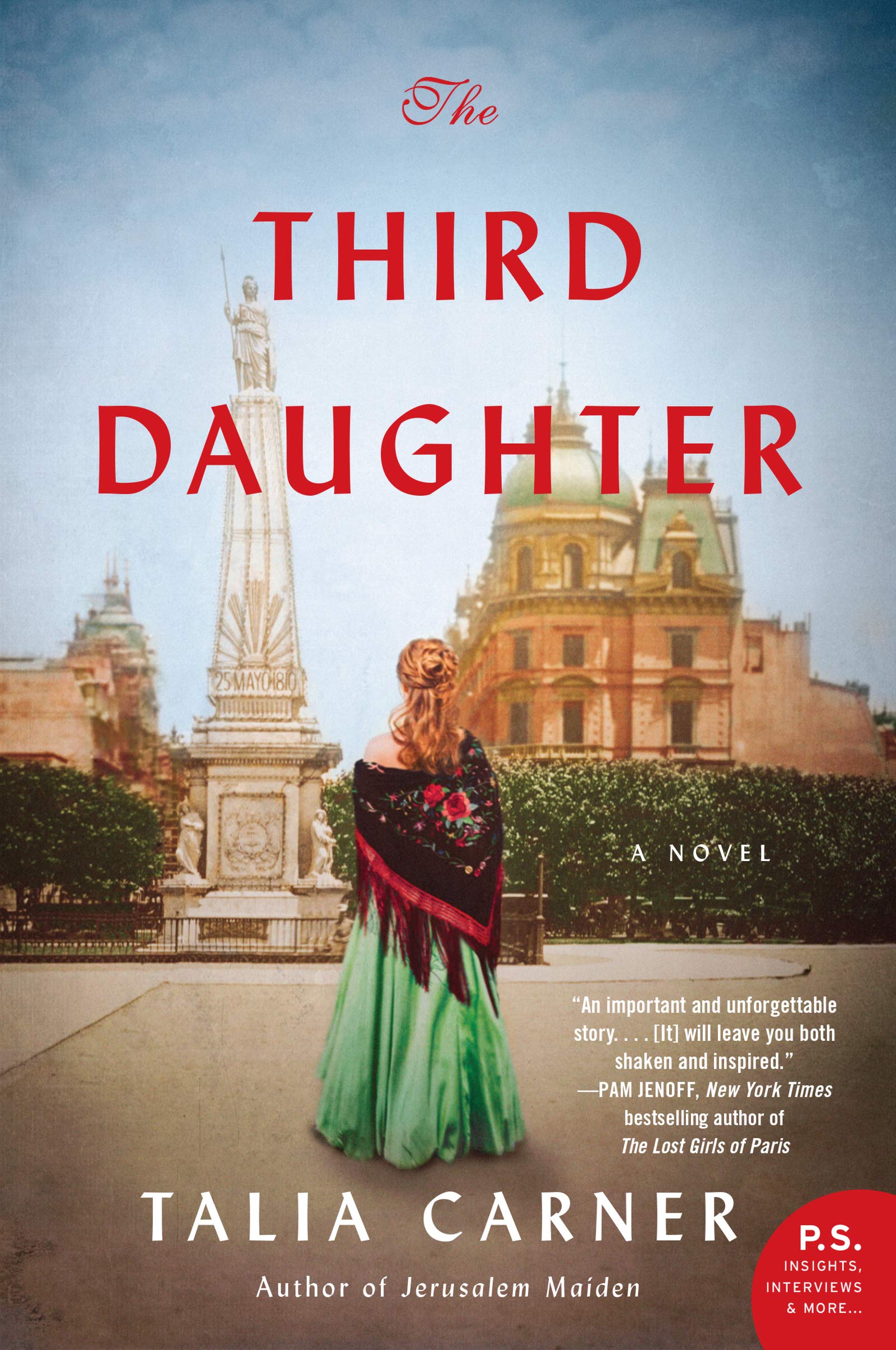

Sex trafficking and exiting prostitution has been a longstanding concern for Carner, who addresses it directly in her new novel, “The Third Daughter.” Carner first encountered the topic in 1995 when she attended the fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. At the conference, Carner, who was then on the business side of magazine publishing as the publisher of Savvy Magazine, gave entrepreneurial workshops on economic self-reliance for women.

In a recent conversation with JewishBoston, Carner recalled how the conference changed her views on freedom from violence. “I knew about sexual violence and rape as a tool of war,” she said. “But I then learned about genital mutilation in Africa and the Middle East, the burning of brides in India over family and dowry disputes, and the sexual enslavement of women. The height of sexual violence against women is sex trafficking, something I depict in my latest novel.”

At The Miriam Fund event, Carner told the audience that two-thirds of prostitutes in the United States are lured from other countries by false promises of jobs. Once they cross the border, their passports are taken away and they are effectively enslaved. Most of these women don’t know the language. They have an innate distrust of law enforcement, which is often corrupt in their countries, and they are not aware of their legal rights. The other third of prostitutes are American girls. Carner noted that most of these girls are between the ages of 12 and 14.

“The Third Daughter” is a realistic and timeless depiction of how young women were trapped into prostitution. Taking place in late 19th-century Buenos Aires, the novel is set in a little-known period of Jewish history when poor girls from Russia and Eastern Europe went to Argentina holding on to a false promise of advantageous marriages. Carner, the author of previous novels that have also concentrated on women’s issues, learned about this shameful episode when she came across a Sholem Aleichem story called “The Man from Buenos Aires.” Appearing among Aleichem’s tales about Tevye, the dairyman, Carner was fascinated that Aleichem wrote about a character that she described as “creepy and sleazy.” She read several translations of the story in Hebrew to get to the essence of the culture and speech. “I channeled Sholem Aleichem as I was writing [‘The Third Daughter’],” she said. “Tevye’s banter with God was so interesting that I incorporated that voice in my work.”

Carner tells the story of Batya, a 14-year-old girl whose parents accept the marriage proposal of a much older, seemingly wealthy man on her behalf. Unbeknownst to them, they delivered their daughter into a life of prostitution. Carner’s research uncovered that these girls were raped and tortured on ships from Russia to South America. To give her story verisimilitude, she learned further details, from the street names in the Argentinian capital from 120 years ago to how women in a brothel in Buenos Aires dressed and ate to how a Jewish union of pimps operated with impunity in South America from 1870 to 1939. “The rest was completely my imagination,” Carner told her audience. “All I needed to know was that Batya was tortured, raped, caged and starved on the ship, and I imagined myself there. There were no diaries found by these women. There were no first-hand accounts.”

Carner asserted that fictionalizing these women’s stories enabled her “to bring out their humanity.” She noted that these women, pariahs in the Jewish communities where they worked, were considered “impure” and shunned. They were denied Jewish burials or entry to synagogues. Yet as Carner pointed out, many of them still retained their faith in God and “wanted to meet their creator as pure.” They took it upon themselves to wash the bodies of their sister prostitutes ritually in preparation for burial. “Many of the prostitutes believed that a dead person carried prayers and good wishes to someone’s relatives already in the next world,” she said.

As for breaking the ongoing cycle of prostitution in the 21st century, Carner believes it starts with education and exposure. “We need to reveal men like Jeffrey Epstein,” she said. “People knew about his crimes a decade ago.”

According to Carner, businesses such as airlines, hotels and credit card companies are “doing something important to change society’s focus from the victims—the prostitutes—to the victimizers, that is, the men who pay for sex. Besides these men’s vulnerability to public exposure, it’s the demand side that drives the business.” She further noted that it is paramount to understand that these women do not benefit directly. “Rather, it’s a third party that reaps the financial benefit,” she said. “By understanding the humanity of these women—and viewing them as exploited victims—the demand can be lowered.”