Four years ago, screenwriter Keith Clarke and his producing partner, Joni Levin, were searching for their next project. The only criterion the husband-and-wife team had was that the new work should be an exploration of the meaning of forgiveness. One night, after watching “Ben-Hur” on television, the couple immediately knew they had found their next film—a reimagining of the 1959 classic for a contemporary audience.

More than half a century ago, Charlton Heston starred as the eponymous Judah Ben-Hur, a Jewish nobleman who endures years of slavery and then goes on to become a charioteer extraordinaire. The movie won 11 Oscars, including best actor for Heston, best director for William Wyler and best picture. In the 2016 version, Jack Huston of “Boardwalk Empire” fame takes the reins as Ben-Hur and brings his own gravitas and intensity to the role.

Clarke and Levin were in Boston last week for an advance screening of the new “Ben-Hur” sponsored by the Boston Jewish Film Festival. “We’d been searching for a long time and wanted to tell a big story in which many people would get that message of forgiveness,” Clarke noted in the Q&A that followed the film.

Inspired by Nelson Mandela, Clarke decided to take on “Ben-Hur” after researching the Truth and Reconciliation Commission set up throughout South Africa to deal with the fallout from apartheid. Building on their ongoing interest in conflict and resolution, Clarke and Levin journeyed to two battle-weary areas of the world: Israel and Ireland. Levin observed, “We spoke to young people who grew up with neighbors who were also their brothers—yet all of a sudden they were at war with each other.”

In both iterations of the film, Ben-Hur and Messala, a Roman, transcend their peoples’ differences and consider the other a brother. The two were childhood friends, but Messala’s wanderlust led him to travel the world with the Roman army. Years later he returns to Jerusalem as an officer. His mission is to crush the Jewish zealots who oppose the Roman occupation. To accomplish this, he asks his old friend to inform on his people. Ben-Hur’s refusal estranges the two men.

Like the 1880 novel by Lew Wallace—from which it was adapted—the 1959 film shows a loose roof tile on Ben-Hur’s house falling on a Roman’s horse during a parade. That precipitating incident causes Messala to turn against his friend and arrest him for incitement—a crime he did not commit. Ben-Hur is consequently enslaved to row day and night below the deck of a Roman galley.

Clarke, on the other hand, departs from Wallace’s book by portraying the event that sets tragedy into motion as a zealot’s assassination attempt on the new governor of Judea. The arrow is shot from Ben-Hur’s rooftop. Clarke said he changed the plot to bring in a contemporary context. “It’s a conflict with the use of zealots who we have today,” he said. “It was a choice to bring that into the world where we are.”

Fraser Clarke Heston, Charlton Heston’s son and a film director who made an animated version of “Ben-Hur” in 2003, applauds some of Clarke’s changes. But in a recent phone interview, Heston mentioned the narrative turns that he misses in this new version, which has been trimmed down from three-and-a-half hours to just over two hours. “The original ‘Ben-Hur’ is a slightly darker, more serious film,” he says. “This [new version] attempts to do everything in two hours, and understandably they had to leave out a lot of stuff. I miss the whole plot involving Quintus Arrius, captain of the galley.”

Heston is referring to the episode of Arrius unchaining Ben-Hur and saving his life when the ship is attacked in an extended battle scene. Ben-Hur, in turn, saves the captain and both of them survive the shipwreck because of Arrius’ act of kindness. “It’s helping your enemy,” says Heston. “That’s really important.”

In the new film, Quintus Arrius’ character is folded into another existing character, Sheik Ilderim, a desert-dwelling horse trader played by Morgan Freeman. Ilderim understands that Ben-Hur is the man to race his prized horses to victory against Messala, the best charioteer in the Roman Empire. “It puts a lot on Morgan Freeman’s character,” Heston says. “He’s the reason Ben-Hur becomes a chariot driver.”

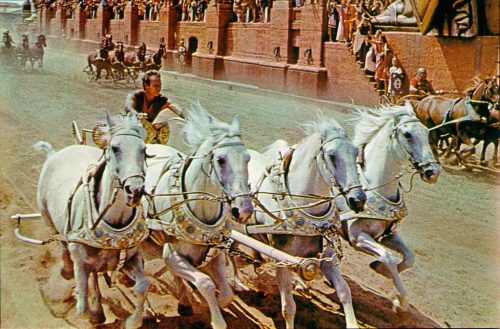

Both films feature the de rigueur chariot scene, with each clocking in at 10 minutes. Although there were some special effects, the 1959 film did not have access to the computer-generated imagery (CGI) of the 2016 film. The entire race then was filmed in camera—that is, placing cameras in pivotal points, including under the chariots—and flesh-and-blood extras, rather than CGI, made up the cast of thousands.

While both versions adhere to Wallace’s Christian vision—the book’s full title is “Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ”—Clarke further noted that he thought of the story as a depiction of a trinity consisting of Judah, Messala and Jesus. “My script is the story of three men, the same age, who are at a crossroads of history,” he said. “One chooses power and betrayal, one chooses revenge, and one chooses the path of peace. I didn’t go into [this project] with a faith-based idea. It’s just that Jesus’ teachings have relevance in the world today, whether you’re Christian or not.”

But the fundamental question still remains—was it wise to remake “Ben-Hur”? “People have asked me the question if it was fair to mess with the original,” Heston says. “It’s been almost 60 years since my dad’s version came out. Why not redo it for a new audience who may not have seen it?”