A century after Louis Dembitz Brandeis took his seat as associate justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, the country’s first Jewish justice is being remembered in conferences, in the media and in a new book by legal commentator Jeffrey Rosen as one of the most influential jurists of all time, whose views on big business, free speech and the right to privacy resonate today.

His swearing-in ceremony on June 1, 1916, capped an unprecedented four-month-long bitter political battle following his nomination by President Woodrow Wilson. It was the first time in the country’s history that a Supreme Court nominee faced such a vehement, headline-grabbing challenge, led largely by Boston’s elite and tainted by anti-Semitism. Brandeis went on to serve on the court for 23 years, stepping down on Feb. 13, 1939, at the age of 82.

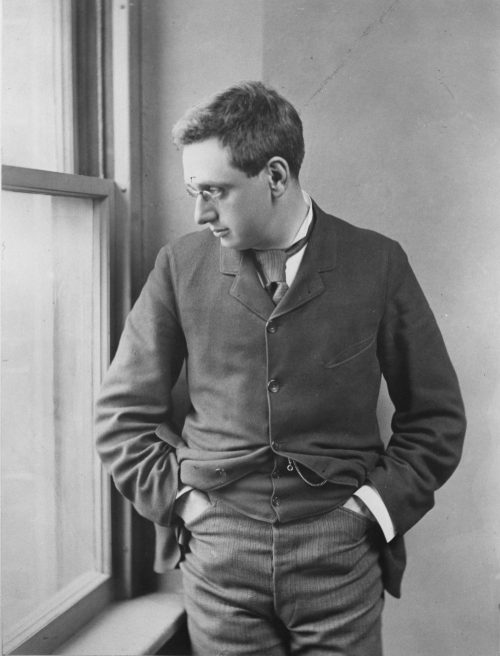

But before Brandeis became one of the most influential and revered Supreme Court justices, the transplanted Southerner was a Bostonian—a Jewish Bostonian—who first arrived here in 1875 as a young Harvard Law School student.

For the next four decades, Brandeis became a successful and influential reform-minded lawyer, as well as an activist against corruption and on behalf of social causes. He advised political leaders, including President Woodrow Wilson. It was also during this time that Brandeis grew into his unlikely role as the leader of American Zionism.

In honor of the centennial year of this milestone in American Jewish history, JewishBoston explored the places in and around Boston where Brandeis left his mark, from the well-known to the surprising.

Harvard Law School, Cambridge

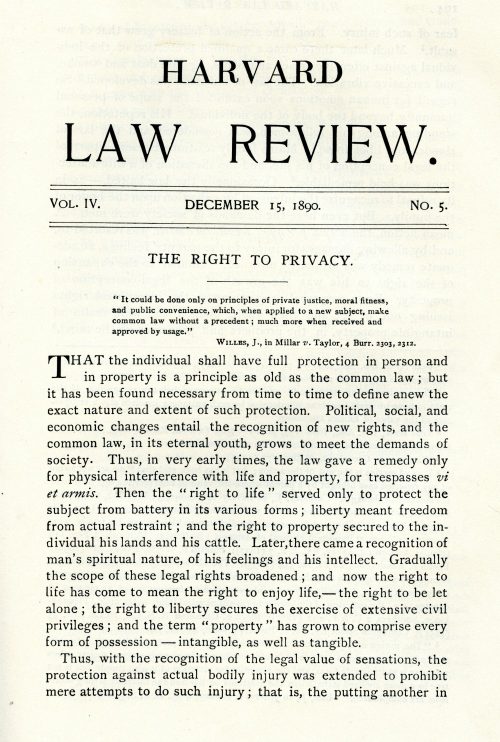

A bronze bust of Louis D. Brandeis gazes out across the entrance of the Harvard Law School library in Langdell Hall, a replica of the original by sculptor Eleanor Platt, which is at the U.S. Supreme Court. Brandeis began his studies there in 1875, at the age of 19. Among his closest friends was Samuel Warren, who later became his first legal partner. Brandeis maintained a lifelong attachment to Harvard Law School, and was among the founders of the Harvard Law School Association and the Harvard Law Review, where in 1890, he and Warren published “The Right to Privacy,” considered by many the most important and still-relevant expression on the subject. Harvard Law School commemorated the centennial with a conference last winter and an exhibit of archival material.

Busch-Reisinger Museum, Cambridge

A less well-known Harvard connection is the Busch-Reisinger Museum, part of the Harvard Art Museums, with an art collection focused on central and northern Europe and German-speaking countries. In 1901, Brandeis was among the founders of an association that established the Germanic museum, later renamed Busch-Reisinger. He maintained some involvement through 1912, according to Allon Gal, author of “Brandeis of Boston,” which he wrote as a doctoral student at Brandeis University in 1980. “The more I learned about Brandeis, the more I came to admire him,” Gal said. “He was open-minded, a real thinker, non-dogmatic. Pursuing truth—this was highly important to his agenda.”

21 Joy St., 114 Mount Vernon St. and 6 Otis Place, Boston

In the 41 years Brandeis lived in Boston, he always lived within walking distance of his office and nearby friends. As a socially active bachelor, Brandeis first rented rooms at 21 Joy St. After he and Alice Goldmark of New York were married in March 1891, the young couple settled in at 114 Mount Vernon St., which they sold in 1900; they then rented an apartment at 6 Otis Place. After the birth of their daughters, Susan (1893) and Elizabeth (1896), the Brandeis’ also owned a weekend home in Dedham, where Brandeis and his daughters enjoyed outdoor activities, including rowing and swimming. They also summered in Chatham.

Nutter McClennen & Fish LLP, Boston

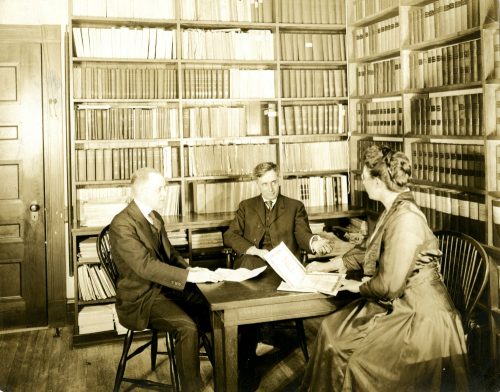

An Andy Warhol print of Louis Brandeis and a collection of Brandeis documents hang prominently on the walls of the prestigious law office Nutter McClennen & Fish, whose origins date back to 1879, when Brandeis and his friend Samuel Warren opened Warren & Brandeis. The rent at the first office at 60 Devonshire St. was $200 per year, or “very cheap, everybody says,” according to a letter Brandeis wrote to his friend Charles Nagel. In 1897, after Warren left the partnership to run his family’s business, the firm officially became Brandeis, Dunbar & Nutter.

On a recent morning at Nutter’s current office in Boston’s Seaport neighborhood, attorneys Michael Bohnen and Tom Jalkut spoke about the firm’s historical ties with Brandeis. Bohnen, a longtime partner at Nutter who is now of counsel, has a small collection of Brandeis legal memorabilia, including a piece of the original Warren & Brandeis letterhead and a letter signed by Brandeis about his planned trip to Palestine in 1919.

“Brandeis created a tradition of professional excellence, legal innovation, pro bono service and civic engagement that continues to inspire lawyers at Nutter today,” Bohnen said.

While Brandeis is most often remembered for his time on the U.S. Supreme Court, Jalkut admires his decades of work as a practicing lawyer. “His career at Nutter gets short shrift,” Jalkut said. “He was an enormously talented lawyer,” who toiled in the day-to-day, often mundane work of the profession.

A longtime partner in the firm’s trusts and estates department, Jalkut administers a trust left by Brandeis’ widow, Alice, which has enabled the firm to maintain a connection with Brandeis’ grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Savings Bank Life Insurance, Woburn

The ordinary facade of the Woburn headquarters of Savings Bank Life Insurance (SBLI) gives no hint of its bold beginnings in the early years of the 20th century. As a reformer and politically savvy lawyer, Brandeis led a legislative campaign, working tirelessly with labor leaders and others, to allow the state’s savings banks to offer affordable insurance to working families. Among the labor leaders was Edward Cohen, the Jewish president of the Massachusetts branch of the American Federation of Labor. “[Brandeis] always considered savings bank insurance his most worthwhile reform,” wrote historian and biographer Melvin Urofsky.

“While SBLI has grown and evolved significantly since 1907, Justice Brandeis’ influence remains,” said SBLI president and CEO James A. Morgan. “His founding mission for SBLI—to offer dependable and low-cost life insurance to all who need it—continues to guide and inspire us in all that we do today.”

Louis Brandeis House, Chatham

Louis Brandeis House, the summer home of Louis and Alice Brandeis, which they bought in 1924 after renting it for a few seasons, is a National Historic Landmark, a designation of the National Park Service, which is also celebrating its centennial year.

Brandeis’ grandson Frank Gilbert, now 86, vividly remembers those Chatham summers, where as a young boy he and his siblings would spend time with their grandparents almost every day. The Gilbert family had their own summer home next to the Brandeis home.

“Grandfather took a real interest in his family and in his grandchildren,” Gilbert said in a recent phone conversation from his home in Washington, D.C.

Gilbert used to read to his grandfather from the latest edition of the Chatham Chatter, a mimeographed newspaper published by his older brother, Louis. During the war, Frank Gilbert had the responsibility of keeping his grandfather up-to-date on world events. After reading the papers and listening to the radio, “I’d run across the field to their house and summarize the news,” Gilbert recalled. “Grandfather referred to this as the Gilbert News Service.”

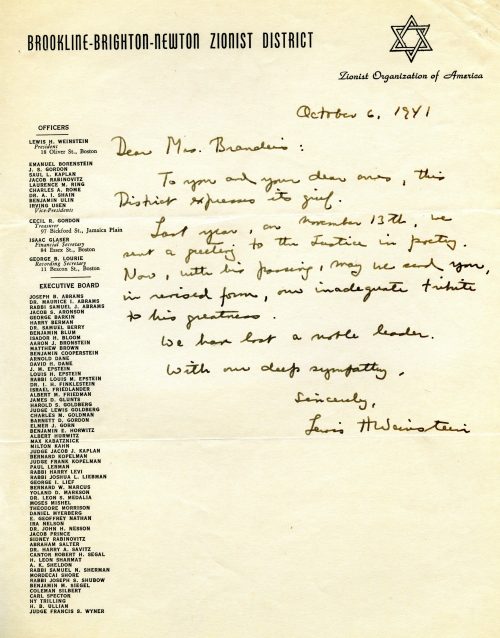

Zionist Bureau of New England, Boston

In 1914, Brandeis assumed the role of chairman of the American Provisional Executive Committee for General Zionist Affairs and set up an office of the local committee at 161 Devonshire St., the same address as his law firm. Brandeis had little to do with his Jewish faith for the first 50 years of his life. He was raised as a secular Jew by immigrant parents from Prague in a family that emphasized ethics and eschewed organized religious practice. He was, however, close with his uncle, Lewis Dembitz, an Orthodox Jew, lawyer and respected scholar of Judaism, who remained a lifelong influence. Brandeis was a founding contributor to the Federation of Jewish Charities in 1895, but “his contributions were regular and minimal,” wrote Gal.

An early influence in attracting Brandeis to Zionism was Jacob de Haas, then-owner and editor of the Boston Advocate, the city’s Jewish newspaper, now called The Jewish Advocate. De Haas was the one-time secretary to Theodor Herzl, founder of the Zionist movement. Brandeis considered de Haas his teacher on Zionism, and they traveled together to Palestine in 1919, which was Brandeis’ only trip to the Holy Land.

As a leader, Brandeis barnstormed the country, espousing a brand of American Zionism that countered the then-prevailing fear that it raised questions of patriotism, according to Jonathan Sarna, the preeminent American Jewish historian and Brandeis University professor. “‘To be a Zionist is to be a better American’ is how Brandeis framed it,” Sarna said in an interview. He added that in his lifetime, Brandeis contributed more than $1.6 million to the Zionism movement.

atop a hill on the campus of Brandeis University. (Photo credit: Mike Lovett/Brandeis

University)

Brandeis University, Waltham

The black robe Louis D. Brandeis wore as associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court is part of a tableaux of items from his office on view in the Goldfarb Library at his namesake university in Waltham. The archives are a treasure trove of Brandeis’ personal and family papers and artifacts, donated largely by the Brandeis family, including an endearing letter Brandeis wrote to his daughter Susan when she was a young girl, and his physics notebook from his teenage days as a student in Germany.

Founded in 1948, seven years after Brandeis’ death, Brandeis University was established as a secular university under Jewish auspices at a time when Jews were being denied access to top-quality colleges and universities. On July 1, Ron Liebowitz took the helm as the major research university’s ninth president.

Frank Gilbert recalled his mother’s involvement in the college’s early years. Susan Gilbert, who died in 1975, was a member of the New York State Board of Regents and offered advice based on her experience with higher education, he said. In 1963, Brandeis University awarded Susan, a lawyer, a doctor of humane letters.

“I think the whole family is very excited about the achievements of Brandeis [University],” Frank Gilbert said. “It’s exceeded our hopes, and it’s become a valued part of life in Boston.”

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE