For two decades, Eric Orner worked for Massachusetts Congressman Barney Frank on and off as staff counsel and press secretary for the House Financial Services Committee. During Orner’s tenure in 2010, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act became federal law. During his stints in Frank’s office, the gay Jewish artist took to doodling events around him in small notebooks and on scraps of paper that eventually shaped a book.

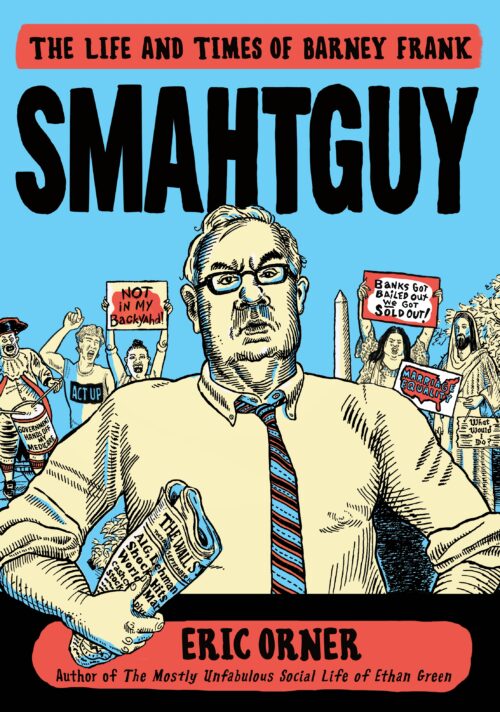

When Frank asked Orner to be his biographer five years ago, Orner realized that at the end of 20-plus years, he could easily fill his archive of drawings with research about Frank’s life. The result is a “graphic biography” of his boss, “Smahtguy: The Life and Times of Barney Frank.” The book is an impressively documented account of Frank’s life drawn with a vivid palette alongside detailed reportage of his prodigious political career.

“I’ve been a working artist, especially in Massachusetts, since I was in college at Tufts University,” Orner recently told JewishBoston. “I sold my first drawing to the [now-defunct] Boston Phoenix in 1981. I always take a lot of notes that are really doodles. Barney is a larger-than-life character and being on his staff exposed me to many impactful and hilarious things.”

Orner’s treasure trove of drawings and notes yielded material focusing on various events in Frank’s political trajectory. Orner noted that these events included the second coming of Michael Dukakis in the 1980s, the Clinton impeachment and the 2008 recession.

Although born in New Jersey, the 82-year-old Frank has come to epitomize Boston. He landed in the city as a Harvard University undergraduate, where he also earned a law degree. He entered politics as a Massachusetts state representative in the 1970s. He continued to have a front-row seat in Boston politics as Mayor Kevin White’s chief of staff during the chaotic days of school desegregation.

Orner said Frank was a “fish out of water in the [Kevin] White administration. There is something fascinating about where this kid with no Boston roots winds up running the city on a daily basis as the mayor’s chief of staff. Barney was particularly talented at organizing while White was more of a big-picture person.”

It was also a time when Louise Day Hicks, an opponent of school busing, mounted an aggressive mayoral campaign against White. “You read a Louise Day Hicks speech,” said Orner, “and it’s the same kind of dog-whistling we see today. Her politics gave rise to what we saw in the 1970s with the powerfully negative reaction to forced busing.”

Against this turbulent background, Frank was an unhappy, restless and closeted gay man. Orner’s depiction of Frank’s struggle in words and pictures is especially poignant. He uses intense, dramatic colors—glowing yellows, salmon pinks and electric blues that set his panels ablaze. Orner’s striking use of colors ushers him in as a gay artist from the margins. His work had mainly appeared in gay periodicals like Bay Windows, where he was the resident cartoonist drawing “The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green.” The popular comic strip began in 1989 and depicted a young gay man attempting to balance his career with his quest for love. It became one of the longest-running gay comic strips in any newspaper.

From 1981 to 2013, Frank’s congressional district spanned a wide swath of Massachusetts, including the southern and western suburbs of Boston. Frank was the ranking member of the House Financial Services Committee at the end of his long tenure. Although Frank’s legislative work is notable, Orner said he also wrote “Smahtguy” to highlight Frank’s critical role in gay history.

The book’s prologue depicts Frank in oppressive blue-and-yellow backgrounds as he is embroiled in a sex scandal. The scandal came to light in 1989, revealing that Frank had hired a male prostitute. It was a jarring admission given that the year before, Orner pointed out that Frank came out “joyously and voluntarily and was celebrated for it. Moreover, it was the first time a politician came out in positive circumstances. He was the highest-ranking member of Congress to come out as gay. Without people like Barney, I would not be living a full and uninterrupted life as a gay man.”

Frank’s liberalism is also a critical part of his story. Orner said Frank’s liberalism “came from a progressive Jewish place. Forces of history like the Holocaust shaped Barney’s progressivism. I would place Barney in the lefty, trade union, New York semi-socialist strand of American Judaism.”

As for Orner, his Judaism took an unexpected turn when he went to work for an outpost of Walt Disney Studios in Jerusalem. Between jobs in Frank’s office, Orner went to UCLA’s film school and worked in animation at Disney. His boss established an animation studio in Jerusalem at the behest of then-Mayor Ehud Olmert. To qualify for tax breaks, the Disney staff in Israel had to employ at least one Jewish story artist. Orner was the artist and lived in Israel for almost three years. “Israel wasn’t on my radar at the time,” he said. “But I quickly identified with the place and its people. I consider it a second home now and go there at every chance. The place is in my blood.”

When Orner lived in Jerusalem, he was continuously asked when he would make aliyah, or immigrate to the Jewish state. One day, a friend pressed him, and Orner admitted that he didn’t know if there was a place for him as a gay man in Israel. The friend retorted, “Why do you think we invented Tel Aviv?”

Orner lives in New York with his partner but said he “loves Boston dearly and that it is the center of my emotional universe.” His graphic biography of Barney Frank—a trailblazing legislator and gay man—places Orner in the pantheon of political biographers and stakes out a special and laudable place for Frank in American history.