There’s a joke in Elissa Altman’s family that she learned how to cook out of self-defense. Self-defense is often in the mix for Altman when dealing with her octogenarian mother, Rita. Altman, who is a noted gourmand, food writer and critically acclaimed memoirist, has once again showcased her distinctive storytelling gifts in a third book entitled “Motherland: A Memoir of Love, Loathing, and Longing,” which will be published next week. The memoir is equal parts homage, meditation and intense reflection about her complicated relationship with her mother.

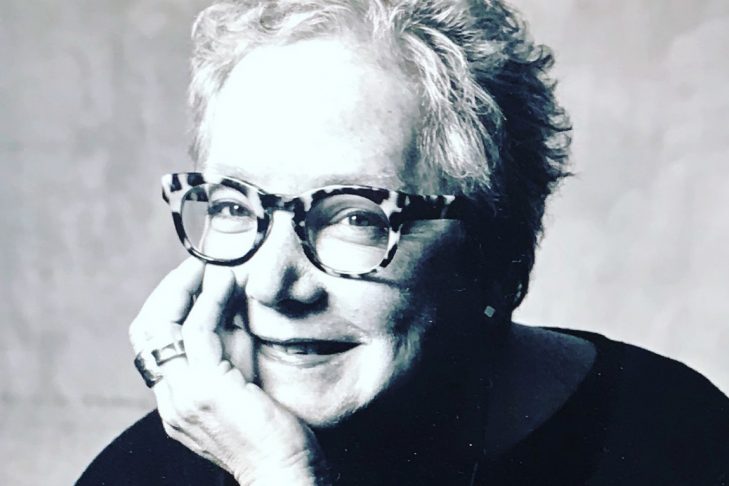

Altman, who grew up in Manhattan and Queens, was her parents’ only child. The mercurial Rita has always been a source of frustration and wonderment to her daughter. Altman recently spoke to JewishBoston ahead of her book launch at Brookline Booksmith on Tuesday, Aug. 6, where she will be in conversation with Joanna Rakoff.

Early on in the book, Altman writes, “Like the Centralia Mine fire, my mother and I have been burning for half a century.” In response to a question about the image, she asserted, “I don’t remember a time when [our relationship] wasn’t smoldering, at the very least.”

“Motherland” grew out of a series of columns that Altman wrote for The Washington Post in 2015 called “Feeding My Mother.” As Altman described it, the pieces were meant to track the arc of her relationship with her mother at the table and as “someone who is now charged with making sure that she eats and that she’s healthy.” Although Altman doesn’t call her mother anorexic outright, Rita had an antagonistic relationship with food that dated back to her childhood as a chubby girl. She starved herself to utter svelteness as a young woman, and she perceived that her beauty and figure were her ticket to the fame she craved.

Rita had her brush with celebrity as a singer on television in the 1950s and as a sought-after model in Manhattan. She often tortured her daughter with the thought that she gave up her glamorous life to become a mother. Despite Rita’s contentious relationship with food—she never ate a complete meal with her family at the table—Altman found love and solace in cooking. She recalled that she “came to the table as a result of my father, who taught me that food was culture, history, flavor, love, affection and entertainment. That utterly compelled me. Growing up in Manhattan in the ’60s and ’70s, my father took me to restaurants he loved and taught me everything he knew about the table.”

Rita’s relentless pursuit of beauty and thinness eventually translated into attempting to make her daughter over in her image. “It’s hard not to conflate the darker and funnier moments in my life with Rita attempting to make me over,” said Altman. “In all the years of her buying me clothes as a child, all of those outfits were miniature versions of her wardrobe. I was an 11-year-old tomboy who wanted to be on the tennis court. My mother believed I was going to be a smaller version of her. That’s the funny side. The not-so-funny side is when she knew she couldn’t succeed in making me over. That’s when I realized she couldn’t separate from me and she couldn’t understand how I could separate from her. I write a scene in the book that happens in my 20s. If I didn’t dress like her, she would dress like me. I went to her apartment for brunch one Sunday, and she answered the door dressed like me in jeans and a T-shirt. It was strange and weird and creepy. That was the first time I realized objectively that there were more than just average mother-daughter issues between us.”

In the intervening years, Altman met and married her beloved Susan, a book designer whom Altman affectionately added is also an excellent cook and outstanding baker. Committing to the relationship entailed Altman’s move to central Connecticut and a two-hour drive from Rita. Altman’s rocky relationship with her mother continued and hit a roadblock when Rita had a life-changing fall three years ago.

The call that every middle-aged child dreads came the day after Altman had come home from a book tour for her second memoir, “TREYF: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw.” Rita had fallen, and Altman’s world was turned upside down. In the aftermath of Rita’s accident, Altman discovered the extent of her mother’s hoarding and shopping addiction. Her description in “Motherland” about that time is one of the more poignant and empathic stories recently written about children and the dilemmas that come with aging parents.

Rita’s fall was also a “before and after” moment for Altman, who knew her mother’s care was her responsibility going forward. Her late father told her as much over lunch in 1979, when he said to his daughter, “You know someday she will be your job.” Altman noted the conversation “imbedded itself into my viscera and stayed with me. When I left New York in 2000 to be with Susan in Connecticut to have my own safer life that represented me, and the way I wanted to live, it was tucked in the back of my head that something was going to happen. I would be called upon to make a decision.”

Altman said she anticipated an eventual full-blown reversal of the mother-daughter roles after her yearlong column had ended. “I realized [the column] was also about an inevitable reversal of roles,” she said. “How do you sustain someone and nurture someone who doesn’t want to be nurtured or sustained with food and other types of support? It was very natural for me to think about writing a book about my relationship with my mother. Everything in life surrounding her has been triangulated, including my relationship with Susan. I knew the column was loosening the bolts and breathing life into this subject for me.”

Elissa Altman will be at Brookline Booksmith on Tuesday, Aug. 6, at 7 p.m. Find more information here.