I had never known anyone who died by suicide until my 19-year-old cousin Ezra succumbed to his war with depression and obsessive compulsive disorder last February. It’s hard to put into words how that felt.

When I arrived at the funeral, his father hugged me tight and said, “He was in so much pain for so long.” I had no idea. Accompanying the guilt about feeling like I could have helped Ezra if I had known was the shock of how and why this animated, curious, intelligent kid with a bright future and fantastic sense of humor was, all of a sudden (to me, at least), no longer here.

What struck me most during the eulogies was that Ezra’s battle and cause of death were mentioned, neither hidden nor highlighted, in a matter-of-fact way: Ezra, as much as he helped others, as much as he impacted the 1,800-plus people who attended his funeral, fought as hard as he could against his own demons until he couldn’t anymore.

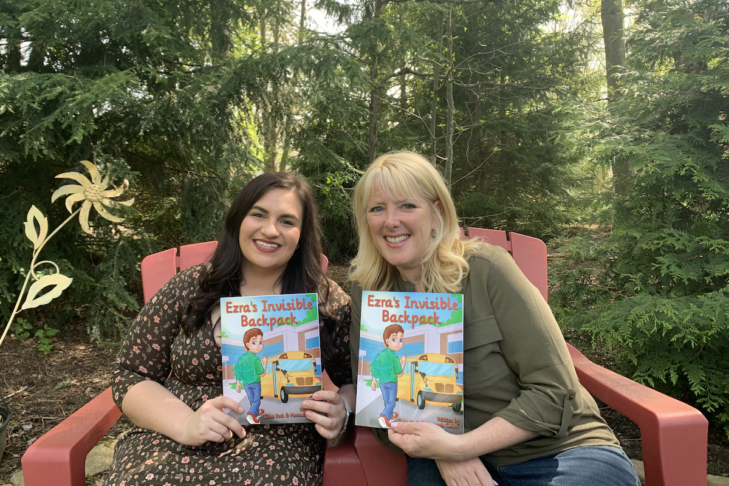

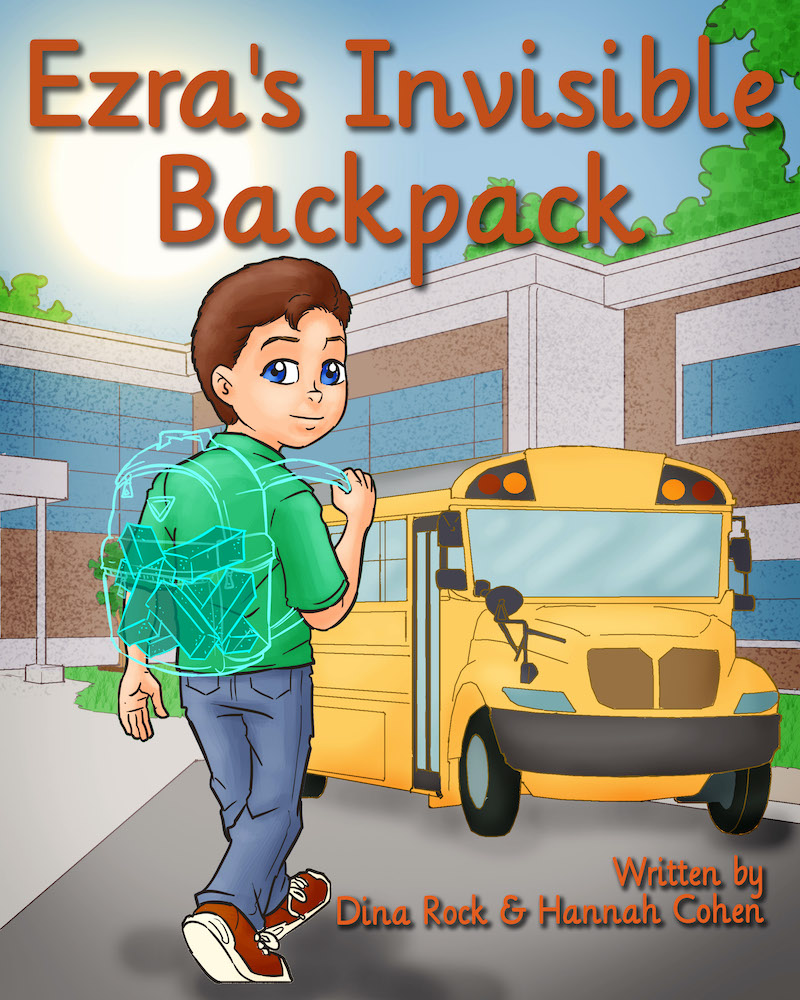

Born from a desire to honor Ezra and help others, his aunt, Dina Rock—a teacher for 32 years—and cousin, Hannah Cohen—who minored in child and adolescent mental health studies in college—set out to write a children’s book about mental health. “Ezra’s Invisible Backpack,” which will be released May 25, gives people of all ages the language and tools they need to communicate their emotions, understand empathy and develop positive mental health. In Rock’s words, “Everybody needs this.”

Though I am not related by blood to Rock or Cohen, we have, through the years, celebrated holidays together. It was wonderful to reunite over Zoom on a happier occasion than I saw them last to discuss their tribute to our beloved Ezra.

Why start with a children’s book? Why is it important to introduce positive mental health to kids?

Hannah Cohen: Teens and adults are starting to become more aware of [mental health], but not a lot of children’s books touch on it. The earlier you introduce the idea that mental health is equally important as physical health, the better kids will be able to handle it going forward, and the more comfortable they’ll feel talking about it. It’s just like any skill, hobby or language.

Dina Rock: These are building blocks that kids need. I’ve been using this concept in my classroom for the last five years or so. No matter what your age is, [an invisible backpack] is something that everybody can relate to. Everybody understands what a brick is and how heavy a brick is. For us, this was a concrete way to express language that was difficult because it’s so abstract.

What was it like trying to convey and tackle that in an appropriate and approachable way for kids?

Cohen: We really did struggle with figuring out how to accurately convey some of these things without also scaring kids or getting too serious. We didn’t want to make this a book that was dark; we wanted it to be something that was happy and made kids feel comfortable. Our initial draft is so different from where we ended up now, in terms of the story. Our character Ezra, at the end, doesn’t get better—he’s not fixed; his anxiety isn’t gone. That was something we adjusted as we were editing because we’re like, no, you can’t fix these things in one day. This is a process, but here are tools you can use in order to help to get better over a long period of time.

Rock: Our goal was to create awareness about mental health and not to write a book about mental illness. So often, people equate the two. And mental health does not lead to mental illness, and mental illness doesn’t come because you don’t have mental health. They’re separate, and we want people of all ages to understand how important mental health is.

Just today in my class, someone said to me, “I think so-and-so has some bricks in her backpack.” And I said, “Oh, I’m so glad you’re using that. Why would you think that?” He said, “I don’t know. It’s just the way she was walking.” I said, “Did you ask her?” He said, “No.” I said, “Why don’t you go ask her if she’s got any bricks in her backpack today?” The idea is not for her to have to say, “Here’s what my bricks are,” because she doesn’t have to say that; nobody has to say that. But building an awareness that you may have bricks in your backpack creates an environment around you of support. Even if it’s something small, the awareness is a really important goal.

I really like your emphasis on mental health, not mental illness, and how it’s just as important as physical health.

Rock: In the last five years, elementary schools are really starting to do a lot with mindfulness. This plays into that, but in a different way: What do you have that you carry with you that you may carry forever? There are permanent bricks and there are temporary bricks, so how do you deal with that? You still can move forward even though you have bricks in your backpack, and that’s an important lesson in and of itself.

I think older generations have a desire to sweep things under the rug, and even now, talking about mental health and mental illness can still be taboo.

Cohen: There’s a lot of stigma in different groups. I feel like people accept mental illness in women a lot more easily; there’s a lot of stigma with men and being a man and being strong. In different races and their communities, it’s really frowned upon to seek therapy. It’s just so sad that it’s not treated with the same significance that physical health is.

Rock: In my class, we were reading this book called “Out of My Mind” about a kid who has cerebral palsy and who can’t talk and tell everybody what’s going on in her head. I said to my students that when you see someone or when you know someone who is going through something, and if you don’t know what they’re going through, I want you to picture a cast on their arm. Because when you picture a cast on their arm, you immediately have empathy for them. That’s why we chose an invisible backpack because it gives you a visual so you can understand, and when you understand the weight of what that can be, it really helps bring that awareness even more.

Hannah, you’ve been open about your experiences with mental illness. Do you think this book could have made a difference for you as a kid?

Cohen: I think so. Even if I’d read it as a middle schooler, or if I had read it to [my younger cousins], I think it would have resonated in me and made me feel less alone. I felt really alone at the beginning of my diagnosis with depression, and I think the book would have given me a kind of comfort of being like, I’m not a weirdo, I’m not messed up, I’m not broken. I just have these bricks and I just have to carry them and that’s OK.

Rock: It creates an awareness of the people around you of how to interact with you and to be more empathetic. It also has the reverse effect of creating an awareness that you’re not alone, so it’s awareness on both sides of the spectrum. I read our book to a family that I know, the dad and mom, their ninth grader, eighth grader and first grader. Three days later, the dad called me and said, “You have no idea how much this book has affected our family. I came home from work today and I just had a really bad day, and [my 7-year-old] came up to me and said, ‘Abba, how many bricks are in your backpack today?’ And we hadn’t talked about the book in two days.”

Cohen: When something resonates with a kid, it sticks in their mind. The backpack is the perfect tool because it’s this concrete thing; it’s something they can picture and they relate to—they carry a backpack. So it’s easy for them to adapt that and translate that into their expression of emotion in their daily lives.

Where did Judaism fit into the process of creating this book?

Rock: I’ve realized as a Jewish person myself and as a teacher in Jewish day schools that Jewish values are everyday human values, like tikkun olam, repairing the world. When we help each other, we’re helping the world. When you save one person, you save the world. Let me help you lighten your backpack, and you help me lighten my backpack and let’s be aware of each other.

What sort of things can kids do with each other to lighten their loads, apart from listening and acknowledging?

Cohen: On our website, we have a worksheet that recommends socializing, being with their family, their friends, doing something that makes them happy and feel good. One of my friends’ and my favorite things to do is just sit and do an activity together, not necessarily talk about it, but just be supportive. I can go to my friends and say, “I’m having a rough day, can we watch a movie? Can we paint?” That’s a great way to lighten your backpack because even if those bricks aren’t disappearing, it gives you an emotional reset and lets you feel a little bit better for the time being.

How can parents begin to have these conversations with their kids?

Rock: I think after reading the book or just starting to have a conversation, it’s so simple, and that’s one of the things I love about our book as well—this isn’t a down-and-dirty, deep, hour-long conversation. This could be something as simple as a check-in. A lot of parents say, “How was your day today?” And the kid says, “Fine.” “What did you do today?” “Nothing.” You know, that kind of thing. So, as you talk about non-yes-and-no questions and non-one-word-answer questions, another question in there is, “How many bricks are in your backpack today?” Not are there any, but how many? And you just give it a number.

As a parent, it’s always been important to me to parallel for them so they see I have issues and I go through things too. It’s important for parents to talk to each other within the kid’s vicinity, saying something like, “I have about 10 bricks in my backpack today,” “I had a rough day at work,” or “So-and-so did this on this account and I didn’t know what to do, and it just added a brick to my backpack today.” So that they hear, “This is not a child issue, this is an issue that everybody deals with, and it’s OK, and here’s how we deal with it.”

Cohen: I also think to approach it like, “We’re going to read a book now,” instead of, “We’re going to talk about mental health,” because the kids naturally latch onto important themes and topics. I think we discredit kids and we underestimate them. If parents start reading this book, kids will take the necessary information out of it and ask the questions they need to ask just naturally.

Rock: We also know that as parents, teachers and therapists, it’s hard to have that discussion, and sometimes it’s not that parents don’t want to, they don’t know how to. That’s why it was so important to us to have discussion questions at the end of the book. We have advanced discussion questions too on our website, if a therapist or counselor or parent wants to have higher-level discussions.

How can Hebrew school teachers, youth professionals and religious leaders foster these discussions?

Rock: I’m starting a new role as the director of learning at a temple on July 1. One of the things I want to create in this curriculum is that when we talk about Moses and historic leaders, what kinds of things were in their backpacks? We always talk about Moses did this and Golda Meir did that. But what was Golda Meir dealing with that she wasn’t showing people? She must have been anxious about blank and blank. Who today is going through that? Relativity and connecting the dots is super important. You can do all that with history and education.

Cohen: One of the things we talk about in our advanced discussion questions is, how does identity play a role in your bricks? What is your race, your religion, your gender, your sexual orientation? Those can all be bricks you’re carrying that are permanent. I think, especially now, in light of current events, people are struggling with their Jewish identity and their relationship with Israel. That’s a thing we have to deal with, so reading this book could help kids understand their Jewish identity as a concrete thing that is with them, and there are all these different things that go along with it.

Rock: You could be in a place where you’re the only Jewish person in the room, and how does that feel, and what is that brick in your backpack, and how do you help people understand when you’re the only person in the room? And how does a Black person feel when they’re the only Black person in a room? There are so many relationships and connections you can make. There’s no end to what the conversations can be, and that’s also what was a really important part for us, that this is not a one-and-done. This is a concept you can use over and over again for the rest of your life.

What do you think Ezra would say about the book?

Cohen: He’d make a joke: “Capitalizing off of me, aren’t you? Trying to make money off of me?” Something funny, because that’s who he is. But I think that inside, he would be really happy that even though he was not able to overcome his battle, [his legacy] is hopefully going to help some other kids out there.

Rock: I think he would be proud of us because he was always big into discussion and education and learning. But he would have laughed first, of course!

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Order a copy of “Ezra’s Invisible Backpack” here.