God Is In The Details

Terumah 5771

We have read some phenomenal Torah the last few parashiyot. Just a few weeks ago, we were standing in front of the water, trapped by the Egyptian Army, which stood behind us, confronting an uncertain fate.

Then, miraculously, the waters part and the Israelites pass through this metaphoric birth canal on their way to safety, while Pharaoh’s army is destroyed.

Thunder and lightning, magical moments!

Last week’s reading also contains a powerful moment. Parashat Mishpatim, a series of laws given at Sinai, presents the details, the laws of how to build a civil society. Then at the end of last week’s parashah, the people exclaim, “Na’aseh v’nishma – we will do and we will listen. God, we are with you 100%.”

After all of that, Parashat Terumah feels a little anticlimactic. Suddenly we are confronted with the details of how to build the Mishkan, the portable sanctuary that the Israelites would carry with them for the rest of their almost 40 years in the wilderness. This is not nearly as exciting unless you happen to be an interior designer.

What is contained within Parashat Terumah?

Well, all kinds of interesting things. I had never heard of a dugong until Rutie taught me that in her d’var Torah.

All kinds of materials are needed to build a sacred space, from the more expected gold and silver and copper to the tanned ram skins, the acacia wood, the lapis lazuli.

To create sacred space, you need details.

Beyond the materials, how do we build this sacred space? What are the dimensions? What kind of moldings? What is the Ark of the Covenant going to look like? What about the bowls and the ladles and the jars in which libations will be offered? What will the lamp stand, made of pure gold, look like?

This is an intricate parashah. It’s beautiful. It reminds me of one of those how-to documentaries like “This Old House,” except it’s “This Old Mishkan.” I guess I can see why that would not have worked.

Maybe a more competitive show like Cupcake Wars would work.

I can see it now: Parashat Terumah: “Battle of the Mishkans.” Who can build the most beautiful and intricate mishkan in an hour and a half given one exotic material, maybe dolphin skins? Who knows? Maybe a unicorn! But Harry Potter wouldn’t like that… But I digress.

This week, we learn of the fifty loops that held the sides of the Mishkan together, the cloths of goat hair, the planks of acacia wood, the inner curtain, the Parokhet, the outer curtain, and all of the accessories.

But wait a second. Why is all this here? While there is nothing wrong with making a beautiful sacred space with exquisite materials, is this what we need at Sinai? Why specifically at Sinai do we have this parashah?

It feels out of place. It feels as if it belongs somewhere else. Now before you get too excited (maybe I’m just speaking for myself here!), you should know that some scholars believe that, in fact, this parashah may have been moved from another section of the Torah.

!!!

In two weeks we are going to read the story of the Golden Calf, which we know takes place while the Israelites are at Sinai, and then we have the actual building of the Mishkan as first described in this parashah with the instructions for how to build it.

Of course, the people make wonderful donations as their hearts move them. So much so that we will read in a few weeks that Moses actually has to tell them to stop because they are donating too much. That is one of the connections which points to this week’s reading really belonging there.

For me, that just sharpens my original question: Why is this parashah here at Sinai?

And, if in fact it was moved, why was it deliberately put here by our ancestors, by Moses, by God – however we want to understand that process?

If someone moved this section here to be at Sinai, it was a stroke of genius. I don’t want to get into a theological conversation and give credit among God, Moses, the Torah’s editors, and our ancestors somewhere along the journey. But somehow one of them, some of them, all of them came up with the insight of placing Parashat Terumah right here at Sinai.

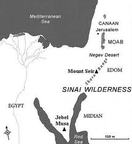

Mt. Sinai is one moment. It is a place that the Israelites visited. In our tradition, it is not a place of pilgrimage. No Hajj here!

We don’t go to Sinai; in fact, it is actually unclear exactly where Sinai is. My roommate and I in 1995 set out into the Sinai Desert to go to the mountain called Jabl Musa, Moses’ Mountain, which contains St. Catherine’s Monastery.

We reenacted Sinai for ourselves – a powerful moment, but not to fulfill any religious obligation, the way Muslims visit Mecca, or even as Jews visited Jerusalem during Temple times or even today. This was not a pilgrimage in the same sense.

Sinai is a place where we experienced God’s presence, but then we left. Sinai is a place where God’s revelation and the core of the Torah is revealed specifically because it is not part of the land of Israel, because it reminds us that the Torah’s impact goes beyond simply the Jewish people. Of course, over the last 3500 years since Sinai, its reach has expanded greatly beyond the Jewish people, being the core of the Christian religion, the Muslim faith, the core of Western civilization.

So again, why is Terumah here?

Because God is not simply in the thunder and lightning of Sinai, in the big moments. God is not simply in the magical moments Sinai, or in the Sefer Habrit, the Book of the Covenant, as we read about last week.

God is in the mundane moments of life, in the sacred messiness of life as Rabbi Irwin Kula wrote in his book: Yearnings: Embracing the Sacred Messiness of Life.

God is to be found ideally each and every day, in each and every moment, in each and every place, in each and every thing.

Now don’t get me wrong. That’s something hard to achieve, and I am certainly far from reaching that ideal. This parashah reminds us that this is something to which I should aspire.

Similarly, the Buddhist tradition says that in every moment you can experience God.

And he said, “Well, for a number of reasons. When the dinner is over, then I don’t have to spend as much time cleaning up, and I can have more time with my wife and my kids.” That resonated.

But he also said that the actual washing of the dishes is sacred, is holy, is kadosh as well.

This struck me as strange at first. Washing dishes does not feel holy. But then I went on a retreat about 10 years ago, a spirituality retreat for rabbis. We alternated between spending the day in the spiritual practices of prayer, meditation, and yoga and in periods of silence. During the simple act of rinsing off my dishes at this retreat, I realized that God’s presence is to be found everywhere. When we stop and listen and think and breathe, God is right there with us in that sacred messiness of life.

One can approach the washing of dishes by complaining. I could turn to Sharon and say, “Oh, can’t you wash the dishes? I don’t really want to wash the dishes. I’m too tired…”

We could get into an argument about washing the dishes. Or, I can wash the dishes, but do it with feelings of anger and disappointment, negative feelings.

Or I can wash the dishes with the sense that is necessary and needed, that it is part of my family’s experience: that having clean dishes will allow us to have wonderful Shabbat meals, that the act of washing the dishes is, in fact, holy, kadosh, just as all the materials that were brought to the Mishkan in this week’s parashah were holy.

This is related to a fundamental teaching in our tradition that I have been working on for years. It is called tadir v’she’eino tadir, what is frequent and what is infrequent. In our American society, what is rare, infrequent, takes precedence. If we see someone, a sports figure, a politician, we are supposed to drop everything and greet them.

But if we see our own partner, our own wife and children, that’s normal – they don’t get the same red carpet treatment. The same thing for days: It is Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur that are supposed to be the most important holidays in our American Jewish thinking, and that’s why most of us come on those days.

But the Jewish tradition is a radical one. In being radical, it teaches just the opposite. It is not the politician or the sports celebrity who is most important, but the people right around us. It is the people with whom we are most in contact who are the most important. Not easy to do – but that is the challenge that our tradition sets up.

And what about sacred days? It is not Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur that are most important, but Shabbat, something that happens every week. Weekly holiness is much more sacred than holiness that appears once a year. Tadir v’she’eino tadir – what is frequent vs. what is infrequent? Tadir kodeim. It is the frequent, the quotidian, and the mundane that take precedence.

But the rabbi, the great Maggid of Mezeritch says, “How wonderful. He has demonstrated to the world that fixing a wheel can be a sacred task.”

That approach, which is found in our tradition and in the Buddhist tradition, is a very challenging one. The acts of paying the bills, driving car pools, picking someone up, buying the groceries, cooking dinner, doing the laundry, paying the taxes, washing the dishes, shoveling the snow, shoveling the snow off your car, and did I say shoveling the snow? These are all sacred tasks.

The building of the Mishkan is taught at Sinai because it is a sacred task. It is revealed right at Sinai to remind us that there is holiness in everything we do. Sometimes we lose sight of that.

Maybe very often we lose sight of that because we’re looking for the bigger moments – the whooshing up moments we talked about last month, the moments where we feel totally compelled by a unique experience.

But those are not the only sacred moments. Often the sacred moments are in the messiness of life. It is in the common moments, it is in what is tadir, and if we can infuse those moments with holiness, with sanctity, then we have really achieved the lessons of Sinai.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE