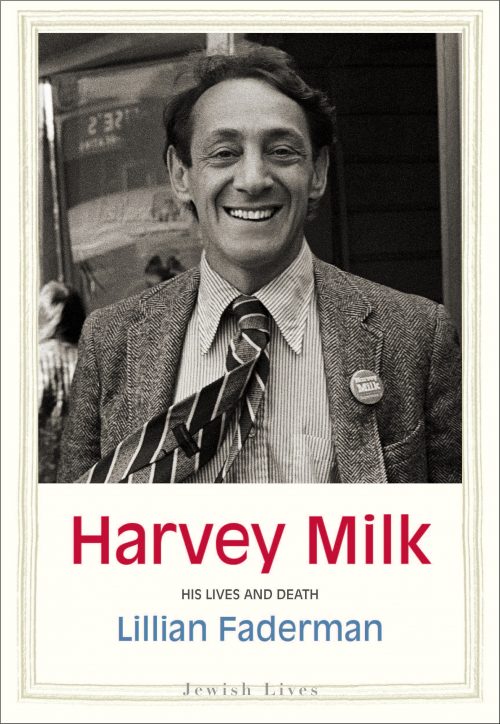

Last week Lillian Faderman spoke at a Keshet-sponsored event discussing her new book, “Harvey Milk: His Lives and Death.” The Harvey Milk biography is among the latest entries in the Yale University Press Jewish Lives series, and Faderman masterfully portrays Milk’s Jewish identity as an integral part of his LGBT activism.

Keshet executive director Idit Klein introduced Faderman and announced that Keshet has partnered with Yale University Press to write guidelines based on the book for high school students. The goal, Klein said, is to send Faderman’s biography to every Jewish high school in the country—Reform, Conservative and Orthodox. Klein further pointed out that Milk is included in Keshet’s LGBT Heroes poster. “Kids in Hebrew schools and college Hillels,” noted Klein, “will see Milk with other people our community holds in high esteem.”

Harvey, as Faderman calls him in the book, was born on May 22, 1930, and raised on New York’s Long Island. She first wrote about Harvey in her book “The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle,” which covers the years between 1948 and 2015. She told her Keshet audience: “I didn’t spend much time on Harvey’s Jewishness in that book, [but] I was very aware of it. I thought about his Jewishness a lot.” When Yale University Press approached Faderman to write Harvey’s biography, she was ready to dive into his life as an LGBT activist who explicitly lived out his Jewish values.

As Faderman pointed out, Harvey was well on his way to becoming a gay icon who was openly Jewish before an assassin’s bullet cut his life short in November 1977. “His oratorical style,” Faderman said, “was very Jewish. He was like the fiery soapbox speakers of the early 20th century on the [Lower East Side’s] Delancey Street. That’s what Harvey strived for. At one point he used an actual soapbox labeled ‘soap’ early in his political career. He was part of the ultra-liberal Jewish tradition. He said, ‘Jews know we can’t allow discrimination if for no other reason we might be on that list someday.’”

In college, Harvey joined a Jewish fraternity and participated in Hillel and the Intercollegiate Zionist Federation of America. Faderman related an anecdote that when he was home from school on winter break, he hung Christmas lights at a friend’s house in the shape of a Star of David. Harvey also witnessed acts of anti-Semitism. The Ku Klux Klan held rallies and cross burnings and the German-American Bund preached anti-Jewish rhetoric on Long Island. She said he was “profoundly affected by the fall of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943, which happened six days before his bar mitzvah. He would come to talk about it often. He said the Jews who fought against the Nazis knew it was hopeless, but when something that evil descends on you, you have no choice but to fight back. It influenced him to fight for justice against the odds as a politician.”

After a stint in the Navy, Harvey lived in many places, including his parents’ house on Long Island, Dallas, New York, Miami and Los Angeles. He finally settled in San Francisco in 1972, where he ran for San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors. He lost that first election and another one in 1975. In 1976 he lost a race for State Assembly. “Here was a guy with a pronounced New York accent who looked like a hippie with his bushy ponytail and facial hair,” Faderman said. “By 1975 he had cut his hair and shaved. His politics remained the same, but he eventually won the endorsements of organized labor, the longshoremen, senior citizens and environmental groups. He barely lost that election in 1975.” Harvey’s persistence paid off in 1977 when the city changed the rules allowing the Board of Supervisors to be represented by specific districts, rather than the whole city.

Faderman observed that the 11 months in which Harvey was on the job as a supervisor was a crucial time for LGBT rights. In Florida, Anita Bryant demonized gays as child molesters and successfully campaigned to repeal gay rights in Miami-Dade, Fla., St. Paul, Minn., Wichita, Kan., and Eugene, Ore. In California, Proposition 6, or the Briggs Initiative, sought to bar gays and lesbians, as well as their supporters, from teaching in public schools. The initiative failed, and in response, Harvey was behind the successful San Francisco vote for the strongest gay ordinance in the country.

But after financing four campaigns, Harvey was practically bankrupt. His business, Castro Camera, which also doubled as an LGBT community meeting space, was failing. Faderman recalled that Harvey turned to his Judaism for solace. In 1977 he went to a gay synagogue in San Francisco for the High Holidays. It was the first time he had been to services since his bar mitzvah. “It felt good to Harvey to be at home with his Jewishness,” she said. “He was always a Jew.”

Harvey had a premonition that he would be assassinated. He famously said, “If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door.” He left taped instructions for the mayor (Mayor George Moscone was assassinated that day with Harvey) to appoint a gay person to take his seat. Moscone’s successor, Mayor Dianne Feinstein, honored his wishes.

This past April, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors voted to name the main terminal at San Francisco International the Harvey Milk Terminal. Faderman said that Harvey might have balked at the honor since he was publicly against the noise and pollution the airport created. What is crystal clear is that Harvey Milk became a martyr on par with John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. Forty years later, his death is both a tragedy and a beacon for LGBT rights.