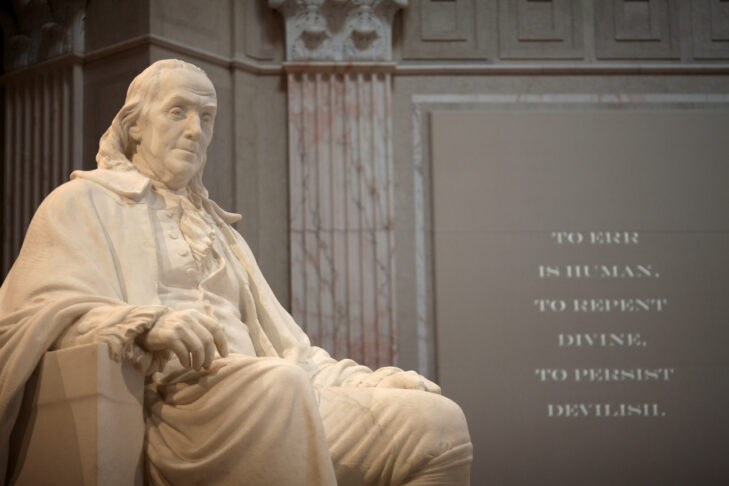

The myth that American founding father Benjamin Franklin (Jan. 17, 1706 to April 17, 1790) was antisemitic first emerged 87 years ago—144 years after his death—with the publication of a fraudulent and since then repeatedly discredited text commonly known as the “Franklin Prophecy.”

On Feb. 3, 1934, William Dudley Pelley, the occultist head of the pro-Nazi Silver Legion of America and publisher and editor of the fascist Liberation, ran an article headlined “Did Benjamin Franklin Say this about the Hebrews?” It contained a supposed excerpt from the previously unknown diary of Charles Coatesworth Pinckney, South Carolina’s delegate to the Constitutional Convention.

As presented by Pelley, the “Private Diary of Charles Pinckney” or “Charles Pinckney’s Diary” recorded a lengthy diatribe against Jews during the Convention, with Franklin describing them as “a great danger for the United States of America” and as “vampires,” and with his calling for the Constitution to bar and expel them from the country, lest in the future they adversely change its form of government.

By August 1934, Pelley’s “Franklin Prophecy” was already being republished in Nazi Germany. Nazi leaders and sympathizers helped disseminate the fraud in German, French and English, and in Germany, Switzerland and the United States.

In September 1934, the “Franklin Prophecy” reached American historian Charles A. Beard, best known for his 1913 work An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States. Beard began searching for an original source for the “Franklin Prophecy,” in the process consulting with other scholars such as John Franklin Jameson, who was chief of the Library of Congress Manuscript Division.

Six months later, in March 1935, Beard’s conclusions were published in The Jewish Frontier, which then reprinted his essay as a pamphlet titled Charles Beard Exposes Anti-Semitic Forgery about Benjamin Franklin. Summing up the results of his investigations, Beard wrote:

All these searches have produced negative results. I cannot find a single original source that gives the slightest justification for believing that the “Prophecy” is anything more than a bare-faced forgery. Not a word have I discovered in Franklin’s letters and papers expressing any such sentiments against the Jews as ascribed to him by the Nazis—American and German. His well-known liberality in matters of religious opinions would, in fact, have precluded the kind of utterances put in his mouth by this palpable forgery.

Henry Butler Allen, director of the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, also weighed in on the fanciful Pinckney diary, stating: “Historians and librarians have not been able to find it or any record of it having existed.”

Beard, Allen, and several other scholars’ responses were collected into the pamphlet Benjamin Franklin Vindicated: An Exposure of the Franklin ‘Prophecy’ by American Scholars, issued jointly in 1938 by the International Benjamin Franklin Society, the American Jewish Committee, the American Jewish Congress, and the Jewish Labor Committee.

A more recent discussion of the emergence and debunking of the “Franklin Prophecy” is found in Nian-Sheng Huang’s Benjamin Franklin in American Thought and Culture, 1790-1990, published in 1994 by the American Philosophical Society. Huang shows the “Franklin Prophecy” to be an extreme case of exploiting, vulgarizing, and distorting Franklin’s legacy. The ease with which it has spread, and its staying power among antisemites and anti-Zionists, demonstrate how successful bigots worldwide have been in misappropriating the American founding father’s good name and fame for their abhorrent purposes.

Throughout his life, Franklin saw a positive societal role for faith and public worship, and generally advocated religious tolerance and inclusivity. In his posthumously-published autobiography, he professed a lifelong interest in projects “serviceable to People in all Religions.” Despite his famous liberality in matters of religious opinions, on a few occasions he did use offensive language about Jews in his private correspondence, though this language does not come close to the antisemitic vitriol he ostensibly publicly uttered in the “Prophecy.” Franklin, who also owned slaves and featured slaves for sale in his newspaper prior to becoming an abolitionist, was not at all times free of prejudice.

In much of today’s popular culture, there often seems to be room only for saints or villains. Franklin was neither. He was a complex person whose ideas and actions evolved as he matured, as he confronted new situations, and as he grew older. Later in life, Franklin became an anti-slavery activist, and he accepted the ceremonial presidency of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in 1787.

In 1788, after synagogue construction and difficult economic conditions plunged Philadelphia’s Congregation Mikveh Israel into debt, its members turned to their neighbors, “worthy fellow Citizens of every religious Denomination,” for assistance. Franklin, who had never been hostile to Jews, led by example in the city and donated five pounds to help ensure the continued presence of Philadelphia’s oldest formal Jewish congregation.

As was fitting for a man who tried hard to be “serviceable to People in all Religions,” when Franklin died two years later the press was able to report that his funeral procession in Philadelphia was led by “all the Clergy of the city, including the Ministers of the Hebrew congregation.”

Remarkably, Franklin eventually influenced Jewish thought and practice. This occurred primarily through his autobiography, which reached the prominent maskil (proponent of the Jewish Enlightenment) Rabbi Menahem Mendel Lefin in Europe. In 1808, Lefin published Sefer Heshbon Ha-nefesh (Book of Spiritual Accounting), which introduced Franklin’s method for character improvement to Hebrew-reading Jewish audiences. This text, with its Franklin-based method, became accepted and valued among mussar (applied Jewish ethics, or practical Jewish ethical instruction) practitioners, made its way into yeshivot, and is still studied today.

The “Franklin Prophecy,” however, shows no signs of going away. It is too useful for those who want to hate.

An earlier version of this article appeared in JewThink on March 8, 2021. Find more by Shai Afsai related to Jews and Benjamin Franklin here.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE