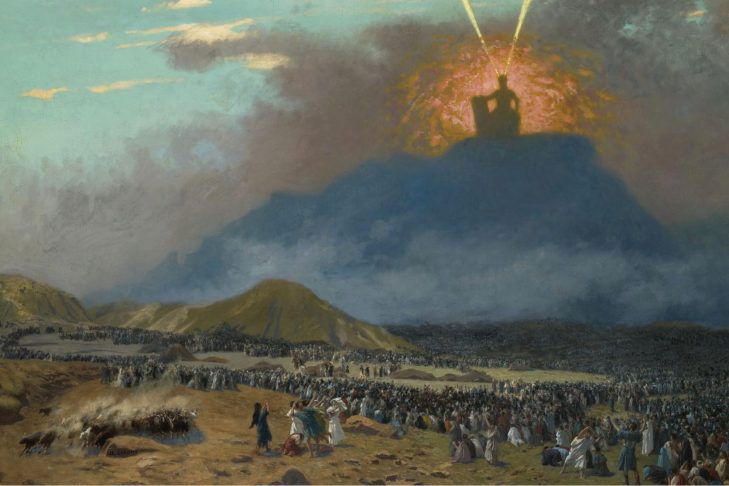

The people stand at Sinai as would-be converts to the Torah covenant, long since created in the mystical realms but yet to be received by the people Israel.

The Torah tells us, it is “…not only with you that I make this covenant and this oath, but with [1] those who are standing here with us this day before the LORD our God and [2] those who are not with us here this day” (Deut. 29:13-14).

The Talmud, Shevuot 39a, famously explains that those who are not with us here this day applies to all subsequent generations of those born Jewish and all converts in the future.

From this mystical perspective, all of the souls of all Jews, including would-be converts, have the Torah inscribed upon them; the covenant is hardwired into us. Parashat Nitzavim hints at this inherent relationship; the Torah, we read, is “very close to you, in your mouth and in your heart, to observe it” (Deut. 30:14).

Often, this midrash from Shevuot is invoked to be inclusive of converts. Once while visiting the shul of Rabbi Michel Twerski in Milwaukee, we were hosted by a pious young couple from Jerusalem. When they heard of my journey, the wife reminded me that the souls of converts, too, stood at Sinai. Her intent was clear: to make me feel encouraged, supported and—at least on a spiritual level—equal to her. That our souls were standing together at Sinai meant that her soul and mine were bound together, made of the same spiritual stuff. I received the intended kindness.

And this teaching does not sit well with me.

Beyond the implications of (a) the ethnicity of souls and (b) determinism that this tradition carries, there is something else.

That some souls are predestined to connect to Torah—which I understand in the most expansive sense—misses what it means to choose Judaism. In another famous Talmudic passage, one sage teaches that God held the mountain above the people and said to them, “If you accept the Torah, excellent. If not, here you will be buried.” To this midrash, Rav Akha bar Yaakov responds, “From this teaching there is a substantial caveat to the obligation to fulfill the Torah” (Shabbat 88a). Rashi explains that Rav Akha is pointing out the lack of freedom-of-choice in this scenario. “If Israel is called to judgment as to why they do not fulfill what they have accepted upon themselves, they are able to respond, ‘But our acceptance was coerced [and therefore null]’” (Rashi, ad loc.).

All of the souls of all Jews past and present, and the souls of all converts, are thus born with the mountain hanging over their heads.

This situation calls to mind the poem Heritage by Chaim Gouri: after surviving the trauma of his father nearly slaughtering him as a sacrifice at God’s command (Genesis 22), Isaac leaves a timeless legacy to his descendants:

But he bequeathed that hour to his offspring.

They are born

And with a knife in their hearts.

Those born hardwired with the Torah in their souls have only the choice between “life and good, death and evil” (Deut. 30:15). The life and good if they choose Torah; the death and evil if they don’t.

This is why I say I was not at Sinai.

I was not born with the mountain hanging over my head; nor was I born with a knife in my heart. These are not choices; these are inheritances. I chose this path because of my Jewish teachers, because of Jewish spiritual practices, because of Judaism’s intellectual maturity, because of the spiritual language of this tradition, and because of Jewish community.

I chose being Jewish because in it I did indeed see “life and good, death and evil.” But in the choosing there was no coercion whatsoever. Quite the opposite. This means that the choice between life and good, death and evil, is a free choice, made based on the merits of Judaism and Jewish people. If there is anything I believe I have to offer as a ger that is unique, it is a Judaism that is not born with a mountain suspended over its head, without a knife in its heart; that this soul was “born” into Judaism having been drawn in by its wisdom, its saints and mystics, and its teachers.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE