Over the years I have become more and more interested and supportive of efforts to bridge the gaps between Arab and Jewish citizens of Israel. Israel a multicultural, multiethnic society with approximately 20% of its population consisting of non-Jews. It is also a highly segregated country. The vast majority of Arabs live in villages or cities made up exclusively of fellow Arabs. The same for Jews. There are of course a few so-called mixed cities such as Haifa, Jaffa, Ramle, Lod and Acre where a substantial minority of the residents are non-Jews, but they are the exceptions.

Perhaps the greatest reinforcer of social segregation is the Israeli school system. This system is divided into four streams: state schools attended by the majority of students, state religious schools which emphasize Jewish studies, Arab and Druze schools, with instruction in Arabic and special focus on Arab and Druze history and culture, and private schools that include the ultra-Orthodox academies. While Arab Israelis are actually entitled to attend non-Arab state schools, very few do and in the case of Jewish students, virtually none attend Arab state schools.

This system has unfortunately produced a very divided society where stereotypes and fears of one another dominate mainstream attitudes. Coming from America where “separate but equal” schools were ruled illegal in 1954 by the U.S. Supreme Court, it always struck me as very problematic that Israeli schools were so segregated.

Twenty-five years ago, two Israeli visionaries, one Jewish and one Muslim, determined to try to shift this reality by creating the first ever bilingual multicultural Jewish-Arab schools, with the goal of promoting integration and mutual understanding between the communities. Over time, these schools have grown to a total of six: some K-12, with others focused on the lower grades. Jerusalem and the Galilee were the pioneer sites for the Hand in Hand (in Hebrew, Yad b’Yad) Schools. Today they have become Israel’s largest network of bilingual, multicultural Jewish-Arab schools.

I had heard about Hand in Hand, and knew this network of schools was generally highly regarded. Indeed, they are included by the Jewish Community Relations Council as a member of the Boston Partners for Peace initiative. But I had never actually observed any of them, nor did I know any families who sent their children. So I was thrilled when a friend from Lexington, Sandra Mayo, who is a gifted Argentinian mixed-media artist and educator, shared with me insights into her experience at the Max Rayne Hand in Hand School in Jerusalem this past spring.

Sandra is one of those people who create opportunities in her wake due to her outgoing personality and openness to the world. Serendipity often plays a role as well. Sandra is a frequent traveler to Israel where she herself lived and studied for many years at the Hebrew University. She is a not only a fluent Hebrew speaker, but also a student of Arabic. Her interest in Arabic stems from her belief that language is the pathway to cultural awareness, and in order to really understand and communicate with Arab citizens of Israel, one must learn the language. So on a recent visit to Israel, Sandra found herself in a well-known knafe restaurant in Abu Ghosh. For the uninitiated, knafe is a traditional Middle Eastern dessert consisting of pastry soaked in a sweet syrup and often layered with cheese or other goodies. Yummy! Abu Ghosh is an Arab-Israeli town on the outskirts of Jerusalem. As fate would have it, Sandra struck up a conversation with the owner of the restaurant who coincidentally worked as a part-time teacher at the Hand in Hand high school in Jerusalem. Together they devised an idea for a creative art-based workshop for Sandra to introduce to the 12th graders at the school. The aim of the workshop was to have the students explore through art aspects of their identity and values that they bring to school about which they may not be aware, and may not feel free to express in more conventional ways. Israel as we know is such a complex society and opportunities for self-reflection are rare. The complexity of Arab Israeli identity is well-known, but rarely discussed especially by teenagers. With a grant from the Massachusetts Cultural Council for her venture, Sandra was off to Jerusalem.

Sandra’s artistic work is unique insofar as it relates to social trauma which stems in large measure from her own biographical background. As an Argentinian, she experienced firsthand what happens in a society when an authoritarian government shuts down the ability of its citizens to think for themselves, express their ideas, ask questions without fear or be curious about their reality. According to Sandra, “doing so through artistic expression can provide a mechanism for discovering your own identity in a complex reality of being an Arab Israeli.” For example, one of the students questioned what national flag fits her, if at all, when the Magen David (Star of David) Jewish symbol on the Israeli flag is not seen to represent her, yet the Palestinian flag may not either, as it can symbolize daily suffering in the West Bank and Gaza to which the same student may not fully relate.

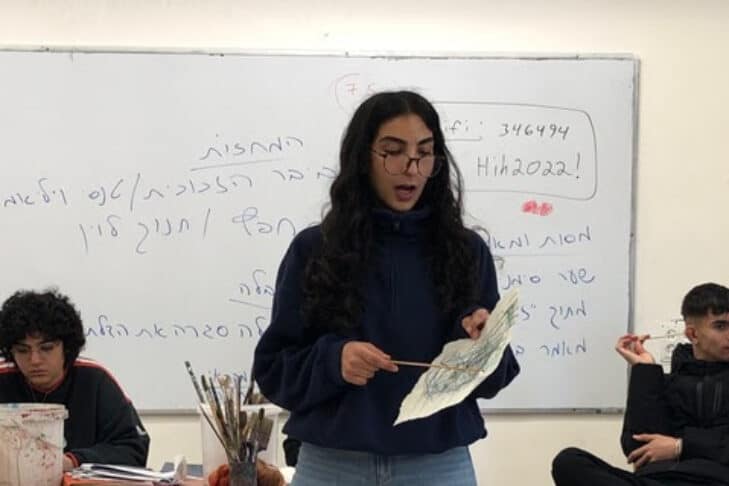

Sandra believed that the students at Hand in Hand might discover a sense of identity and empowerment through artistic expression. “My thought was that students will find similarities between their current life and my story in Argentina since as a member of the Jewish minority, I lived through a military coup with political restrictions. I hoped they would feel free to discuss and express their struggles through art.” She conducted a one-day workshop at the school in which students crafted pieces that represented the values and stories they individually brought to the school, and together created a tangram or puzzle symbolizing their shared community. To introduce the assignment, Sandra spoke to them in Arabic of her personal history in Argentina, which immediately grabbed their attention.

While conducting her workshop at the school, Sandra noticed several aspects that surprised her. For one thing, although she assumed the school would have roughly an equal number of Jewish and Arab students, in fact none of the 12th graders were Jewish. While there had been Jewish students in the earlier grades, none remained by their senior year. She was told that the school began in the lower grades with a class that had been 60% Arab and 40% Jewish.

Sandra observed that although the Arab students could understand her Hebrew, when they wished to discuss the more emotional aspects of their art projects, they reverted to Arabic and their teachers would translate into Hebrew. This of course made sense that students would choose the language they were most comfortable in when discussing sensitive matters. Regarding the overall impact of the school on creating social change for the students, Sandra made the following sobering observation: “Once you step out the school doors, you realize that the reality and world these kids live in doesn’t support the work of Hand in Hand, so students live in a dichotomy bombarded by mixed messages.”

Observations regarding the teaching staff were very uplifting. There was a 50/50 balance in the numbers of Jews and Arabs. Moreover, the teachers seemed very idealistic in their vision for the school. “The teachers functioned like a dream come true, with real collaboration among the staff. Exchanges about students’ difficulties with the Bagrut (matriculation examination) were discussed in two languages going back and forth. Meals, homemade snacks, Arab style nana mint tea and Arab coffee would magically appear in front of you in seconds.”

As Sandra shared her experiences with me, we both felt somewhat let down as in several ways the school fell short of its lofty goals to create a shared society for Jewish and Arab children. So I decided to dig deeper and in so doing, I have come to the conclusion that there is indeed great value in the Hand in Hand schools, but a more nuanced perspective is required as well as more realistic expectations.

The network of Hand in Hand schools was actually the subject of an in-depth study by education researcher Dr. Zvi Bekerman in his 2016 work entitled “The Promise of Integrated Multicultural and Bilingual Education.” The book outlines many aspects of the complexities beneath the surface of this model of bilingual education. For example, the basic motivation for enrolling children in such a school is very different for Jewish and Arab parents. The Jewish parents, who of course are the majority group in Israel, are more ideological in their desire to bridge the gaps in Israeli society and acquaint their own children with the “other” so as to demystify the myths they hold and the fears they have of their Arab neighbors. The Arab parents on the other hand choose these schools because they see them as superior to the average Arab state schools which tend to be under-resourced. Hand in Hand is seen as a means to achieve social mobility for their own children in Israeli society. Not only is Hebrew language proficiency a must, but learning to speak Hebrew without an Arabic accent is a major incentive. The Jewish parents on the other hand have little interest in their children actually mastering Arabic. For them, the exposure to the language is enough.

For the most part, the Arab parents come from upper middle-class backgrounds and see these schools as elitist and a step up from the state schools. While they seek greater social mobility in Israel, some fear that their children might lose their pride in their Arab heritage and become too assimilated. Their Arabic itself may suffer. Both groups shun interethnic dating which is why there may be a drop off of Jewish teens in high school. In general, the schools have a harder time attracting Jewish students and keeping the desired 50/50 balance between the groups, even in the younger grades.

But despite these drawbacks, there is still tremendous value in the Hand in Hand model. However, it’s essential to have realistic expectations of what goals are actually achievable. In order to better understand the experience from a parent’s perspective, I spoke with Moshe Perez, one of the founders of the Beit Beryl Hand in Hand school near Kfar Saba in central Israel which his two young sons attend. Moshe is of Turkish Jewish heritage and is himself an Arabic speaker. He is spending this year in Cambridge as his wife is a Wexner Israel Fellow studying at the Harvard Kennedy School. Moshe had been teaching Arabic to members of his moshav (village) for many years, so it struck him that it made perfect sense to establish a school that would attract a mix of Arab and Jewish students, given the close proximity to Arab townships. The school is in growth mode, having begun as a preschool and now going up to sixth grade. There are approximately 150 pupils in the school. Moshe explained that it is always a challenge to maintain the desired balance between Arab and Jewish children, as Arab parents are more interested in enrolling their children.

When I asked Moshe if he thought the school builds a foundation for a shared society and peaceful co-existence between Arabs and Jews, he said he sees the goals as more modest, though no less essential. As a first step, each group needs to be exposed to the culture and mentality of the other and to their language. By educating them together in two languages, the children “don’t have a fear of the unknown.” Co-existence efforts can only be accomplished by “baby steps,” according to Moshe. He also noted a benefit that seems less obvious: By attending this school and seeing and learning about Islamic culture and Moslem holidays, Moshe sees his boys taking more of an interest in their Jewish identity and Judaism. This is something that would not happen had they attended a traditional secular state school.

I had the opportunity to speak briefly to Moshe’s 10-year-old son about his school experience. He told me he has play dates with his Arab friends and noted that their homes were much bigger than his and his Arab friends have more toys! He also noted that Muslims only have two holidays while Jews have many more, which I assume is something he might have taken for granted otherwise. When I asked him how to say “I’m fine” in Arabic, he responded with “Hamdilla,” which means “God be praised.”

I asked Moshe what happens on fraught national holidays such as Yom Ha’atzmaut (Israel Independence Day) which Israeli Arabs view as the Nakba, or “disaster,” which refers to their perceived violent displacement in the 1948 War of Independence. While challenging, the students acknowledge these different narratives in the school and Moshe reports that Jewish children come to understand that what represents happiness for them is “someone else’s sadness.” However, he stresses that this does not mean that Jewish children themselves must feel sad on Yom Ha’atzmaut, but they just need to understand a divergent perspective. In other words, while respecting Arab sorrow, one can still remain a proud Zionist.

I applaud this attitude and the effort to transmit this duality to the children of Hand in Hand. These schools are far from perfect and hold within them all the complexity and imperfections of Israeli democracy itself. But what Sandra and Moshe have illustrated is that the effort to bridge divides through language and culture are well worth it, and deserve our attention and support. As my late father used to say, “The perfect is the enemy of the good.”

And how is it going now, in the midst of the Israel-Hamas war? Moshe told me that a fellow Hand in Hand parent reports that the school is “an island of sanity in the surrounding craziness.” Indeed, The New York Times just featured an article praising the Hand in Hand schools’ ability to smooth the waters of division during such an obviously fraught time of intense crisis. In the words of a student in Jerusalem in Arabic: “We need to be friends with each other and not fight.” “We can live in peace,” said another in Hebrew. As the founder of the Haifa school put it so aptly, “We can’t stay apart in our comfort zones.”

Hand in Hand schools are tackling a seemingly insurmountable challenge, but the results are promising. Now that should give us all a bit of hope for 2024 and beyond.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE