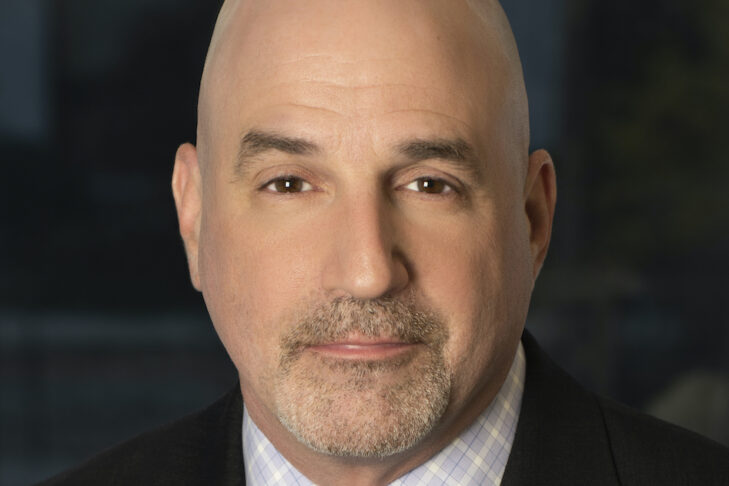

Jonathan Rapping worked for over a decade as a public defender upholding the rights of low-income defendants in our nation’s courtrooms, before moving to the South to address criminal justice reform beyond the courthouse. Toward that goal, he formed a nonprofit organization called Gideon’s Promise, named after Gideon v. Wainwright, a 1963 Supreme Court decision that ruled that anyone who cannot afford a lawyer may be appointed one. Now he’s sharing his insights in a book of the same name.

“The biggest challenge public defenders face is that they come to work because they care about people, they want to help stop and prevent injustice, and they’re thrown into a system that’s inundated with the most inhumane, unjust treatment of people you come to know and care about,” Rapping said in a phone interview with JewishBoston.

Rapping—who gave a sermon during the virtual High Holiday services at Vilna Shul this year—has multiple sources of inspiration for his work. He grew up in a Jewish family in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh, where he celebrated his bar mitzvah at the Tree of Life synagogue, now known for the tragic mass shooting that took place two years ago this month. Rapping’s activist mother instilled a desire to speak out against governmental infringement of citizens’ rights. He has learned about the difficulties that many people of color face in courtrooms through his wife, Ilham “Illy” Askia, who is Black and whose father was jailed for 10 years when she was a child.

Today, public defenders face a crisis, Rapping said. He described them as overworked and underpaid in representing 80% or more of the people who pass through the criminal justice system.

“I firmly believe that as public defenders, our job is not to make our own definition of guilt or innocence or determine who’s worthy of a good defense and who’s not,” he said. “I believe all of us are. The protection we all expect is only as good as the protection we’re willing to afford everyone.”

He laments the current numbers of 2.2 million people in America’s jails and prisons, with nearly 7 million under some form of correctional control. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he worries that people who are presumed innocent might contract the coronavirus while in jail waiting for a trial. He sometimes refers to the criminal justice system by a different name—the criminal legal system—because he questions whether it actually serves justice.

“Our criminal legal system is reserved almost exclusively for low-income people, disproportionately people of color,” Rapping said. “The vast majority of these people, four out of five or more, cannot afford a lawyer.”

Despite these difficulties, Rapping has not only stayed in his career, he’s increased his advocacy of the profession. As the founder and president of Atlanta-based Gideon’s Promise, he works to create a cohort of engaged public defenders in areas that he said particularly need it, including Georgia. Along the way, he won a MacArthur Foundation “Genius Grant” and earned praise from such voices as Bryan Stevenson, author of “Just Mercy” and the inspiration behind the national memorial to victims of lynching.

“Primarily what we do at Gideon’s Promise is train lawyers, do mentorship and training, and do more to help lawyers maintain their spirit,” Rapping explained.

Rapping credits his father, who lived in Boston until his death in 1991 and taught at Brandeis University and the University of Massachusetts, with teaching him Jewish values. Inspired by tikkun olam, he said his Judaism helps him stand up against injustice.

“I was born in the ‘60s and grew up in the ‘70s, not far removed from the Holocaust,” he said. “I understood in theory how important it is to always stand up to governmental oppression. I think it had a lot to do with why I became a public defender.”

He reflected on his experiences while working on the book over about two and a half years. He would wake up at 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. to write before his two kids got up. Not only did he continue running Gideon’s Promise, he kept teaching full-time as a professor at John Marshall Law School in Atlanta. He also teaches at Harvard Law School three weeks a year through its trial advocacy workshop. He said that, “Boston actually has some really good public defenders,” but that while Massachusetts in general has a “really good system” and “really good training programs,” its public defenders are “still under-resourced; they still don’t have the resources they need.”

Rapping’s goal is to change what he calls the culture of public defense in the U.S. toward an approach that he described as centered on the clients’ needs. He explained that when he meets with a defendant he is representing, he cannot substitute his own wishes for theirs, but rather present all of the options so that his client makes an informed decision.

A lack of access to information about the legal system is one of the obstacles faced by Rapping’s clients, he said, adding that they can be pressured into accepting plea deals that may carry a less severe sentence than if the case had gone to trial. Yet, he said, this is contrary to the founding fathers’ wish that every citizen would have the right to a trial by jury. He also noted that a conviction carries what is called “collateral consequences” for an individual. In some states, they might lose their right to vote, access to public housing or certain employment opportunities. It could leave their families homeless and themselves unemployed.

“We have to present to our clients really difficult choices about their lives,” Rapping said. “Not only them, but their families and children. We help our clients with really hard decisions.”

Whether it’s giving a client the most informed advice possible or helping to build a new generation of engaged public defenders, Rapping keeps looking to fulfill the promise of Gideon v. Wainwright.

“What Gideon’s Promise is doing is building a mass movement of public defenders in some of the most challenging jurisdictions in the country,” he said. “We want to lift up the voices, the humanity, of the people being impacted, and push for transformative change.”

Gideon’s Promise is hosting a free virtual event, “A Night to Celebrate 2020,” on Thursday, Oct. 15, featuring performances from Grammy-winning singer Grace Weber and Grammy-nominated singer Wayna, with an auction hosted by former NFL player Champ Bailey. Find more information here.