Ask artist Joshua Meyer if there’s anything particularly Jewish about his work, and he replies that the question should be flipped. “I would say, is there anything not Jewish about my work?” he recently told JewishBoston. The Cambridge-based artist commented that his life is “embedded with all sorts of structures and rhythms that come from Judaism, and it’s also built with the same sort of structures through painting and art. Both Judaism and art are omnivorous; they take up everything in my life. They take up all of the space that’s there, and so that means they inevitably are going to overlap.”

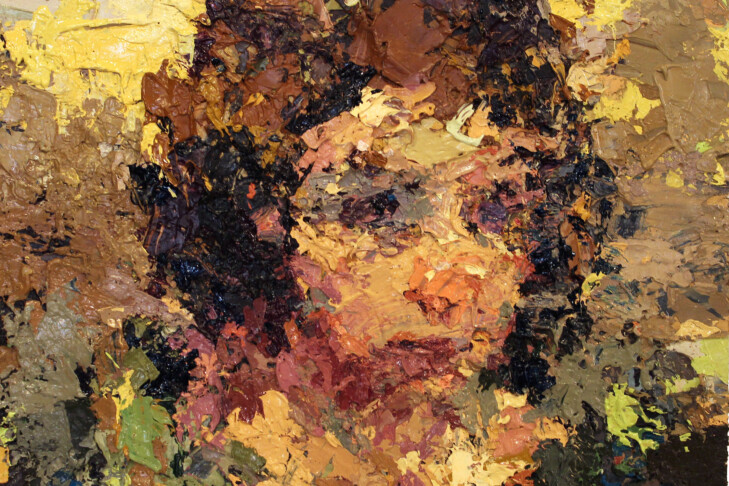

Known for uniquely layering his paintings to both obscure and reveal his figures, Meyer’s pieces are at once intimate and exploratory. He said that when he works on a painting, he aims “to implicate the viewer in the process. I want them to feel as if they could be in the studio with me, making decisions in real time.”

After Meyer graduated from Yale University in 1996, he moved to Cambridge and has been there ever since. A virtual tour of his studio reveals how he sees his “work in transition—it’s so deeply at the core of what I’m doing. Paintings take months or years to do, which gives you a real sense of change and transition within a single painting.”

Meyer regularly shows his work in New York, San Francisco and Provincetown. His paintings will be featured next month at the Rice/Polak Gallery in Provincetown, in a show called “Chronicity.” Meyer said the work is about time and “about the layers of time building on each other and coming out of it.”

Meyer pointed out a quote from Kafka on the wall of his studio with which he sometimes disagrees but that always makes him think. It says: “We Jews are not painters. We cannot depict things statically. We see them always in transition, in movement as change. We are storytellers.” Said Meyer, “Kafka does not give credit to many amazing painters who can contain time within the four edges of the canvas.”

Meyer will be talking about his artwork and presenting a virtual preview of “Chronicity” on Monday, July 27, at noon as part of Jewish Arts Collaborative’s ongoing virtual series in the arts. (Register here.)

Let’s talk about your process in light of the following description: “Meyer is known for his thickly layered paintings of people and for searching open-ended process. ‘Can we truly see anyone close up?’ The Boston Globe asks. These aren’t so much portraits as they are depictions of intimacy. We think we know our loved ones, but do we?”

Process is key to me. I try hard not to have an end in sight when I start a painting. However, I have a series of recurring models. They are all people who are very close to me. We jump in when we start a new painting, and we see where it goes. The process is about exploration; it’s about the way paint works. But it’s also about the way the relationships work; it’s about how we change and how we grow together. So, it’s seeking something, it’s looking for something. The painting itself displays its own process.

One must pay close attention to look through the layers to locate the figures in your work. And that seems to be very deliberate on your part. How did that style evolve for you?

The layers do a couple of things. They help with the hide-and-seek game these models play. But the layers also show the process. You see how we get to something one step at a time. And then something gets covered up, and then it gets recovered. I’m not trying to hide the process; I want it to be on the surface. Being able to see the thickness and the depth and the texture gives people a sense of not just what I’m painting, but also how I’m painting and how it’s coming into being. I want to implicate the viewer in the process. I want you to see what it feels like to be an artist, a painter, and to be in the studio with me making decisions in real time.

What brought you to Cambridge?

I guess New York brought me to Cambridge. I was raised in Connecticut, and I knew I wanted to live in a city, and being from central Connecticut, I thought there were only two cities in the world—the one to the north and the one to the south. And I knew that artists were supposed to move to New York City. But I’m a contrarian by nature. I went to Cambridge instead, and I’ve been here ever since.

You went to Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem in the mid-1990s. What was that like?

I wanted to get a sense of what was going on in art in Israel, and to ask some of the questions that Jewish Arts Collaborative has been asking—where are the overlaps between art and Judaism? These two omnivorous things eat up everything in my life. I wanted to see how they interacted. It was also an interesting time in Israeli art because it really came of age around then. Up until that point, Israel’s art had been made early in the history of the country and looking more toward Europe. When I look back at what’s happened since then, there’s a lot more work [in the country] that seems intrinsically Israeli.

What do you plan to address in your upcoming JLive presentation?