Lesléa Newman altered the cultural landscape in 1989 when she published the groundbreaking children’s book “Heather Has Two Mommies.” Newman’s oeuvre of more than 70 titles includes poetry, fiction and children’s books that have won numerous awards. In her work, Newman has explored Jewish identity, LGBTQ issues, eating disorders and AIDS. She is a National Jewish Book Award recipient, most recently in 2020 for her children’s book “Welcoming Elijah: A Passover Tale with a Tail.”

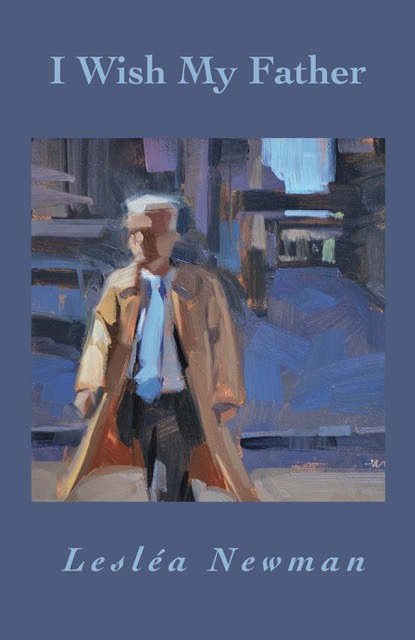

Newman’s newest book is a volume of poetry, “I Wish My Father.” The book follows Newman’s poems about her mother that were published in 2015 in a book called “I Carry My Mother.” Those structurally formal, realistic poems address her mother Florence’s death chronologically. Newman recently told JewishBoston that reading poems about his late wife was a very emotional experience for Edward Newman. “He and I knew that I would write a book for him too when his time came,” Newman said.

Newman noted that writing “I Carry My Mother” and “I Wish My Father” kept her parents alive for her. “I could feel them sitting next to me,” she said. “I could smell my dad’s cologne and hear his voice. Finishing the books was letting go of them in different ways.”

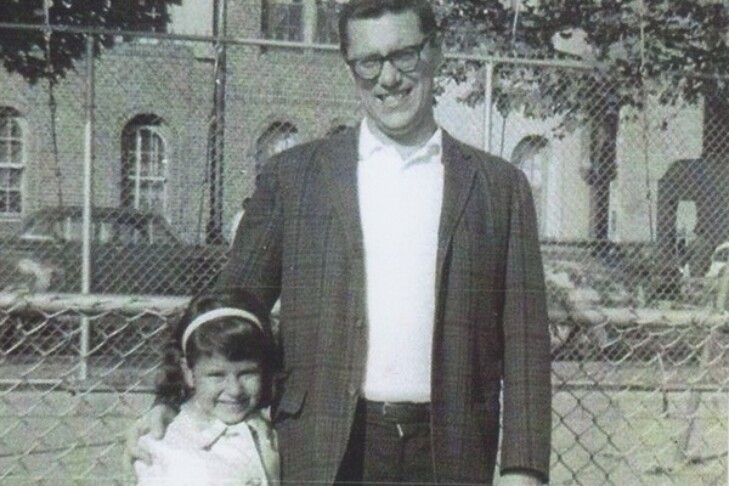

Edward Newman was born in Brooklyn in 1927. Newman said her father worked his way out of an impoverished childhood to success as an attorney and CPA. The family settled on Long Island, where Lesléa grew up.

Newman explained that the 28 poems that comprise “I Wish My Father” are part of a cohesive narrative. “The book is essentially one whole poem written in tercets,” she said. “It begins with my mom’s death and ends with my parents happily reunited based on my vision of the world to come.” Newman noted that the last poem in the volume, “My Mother Is at Bridge,” was important for her to write. “Everybody knows the ending of the book, but I didn’t want to end with my father’s death,” she said.

Newman’s hope for readers who encounter these poems about her father is that “they get to know him and appreciate what an interesting, unique, kind, generous and sometimes frustrating man he was. I also hope that people see themselves in the narrator and their parents in my parents.”

The three poems reprinted below represent Edward’s new, sometimes bewildering, life without his beloved Florence and his subsequent death.

“When My Father Wakes Up”

on that first sweltering night

of that first scalding summer

soaked in sweat like my mother

when she suffered those terrible

hot flashes 40 years ago,

he stumbles out of bed

and lumbers to the archaic air

conditioner, fumbling for the right

button to bring it back to life

with a wheeze and

a groan and a thump. Next he shuffles across

the faded carpet, slides between

the worn sheets, and lifts the torn

blanket to cover my mother

who will surely grow stiff

from the frigid air blowing

between them as she had

for more than 60 years.

Who could blame him

for forgetting she had left

him and was now slumbering

on the other side of town

wrapped in a shroud beneath

the stony, stubborn ground?

How he missed

her old cold

shoulder

“Without Warning My Father”

is sprung from the hospital early Friday

evening, seeming no better yet no worse

according to the doctor who dismisses

him with an indifferent wave of his hand

a little too eager to get on with his weekend

plans. My father refuses my offer of help

and gets dressed in slow motion, then insists

that I pack up a week’s worth of newspapers,

a half-empty box of tissues, a flimsy comb,

a toothbrush, and a kidney-shaped pink plastic

spittoon. Satisfied that he is leaving nothing

behind, he smiles and waves like royalty

as an aide pushes him past the nurse’s station

down the long hallway, into the groaning

elevator and out to the parking lot.

It’s not until we drive halfway home and stop

at a red light where a family of five crosses

the street—father in gray suit with white sneakers

gleaming on his feet, mother in long dark skirt,

daughters all dolled up, subdued and somber—

that I realize it’s Yom Kippur, the Holiest

Day of the year. “Gut yontif,”

I say to my father, pointing. He stares

but does not wish me a good holiday

in return. When we arrive home, he heads

straight for the den and instantly falls

asleep, a lazy boy in his La-Z-Boy,

hands clasped on chest, thumbs twitching

through his dreams. Darkness falls

an hour later and he startles awake,

looks around as if he has no idea

where he is, sees me, sighs, says

“God will forgive us,” and dozes off

again. I tuck a green and black afghan

my mother knit 100 years ago

under his chin, as I remember sitting

in synagogue with my father when I was

a little girl. How I loved braiding the tzit-tzit

of his tallis, the white fringe so smooth

and cool beneath my fingers, while the men

all around me swayed and prayed, their deep

voices wringing as much sweetness

and sadness out of those ancient words,

as they could, that heartrending Hebrew

comforting me like a soft shawl wrapped

around my small slender shoulders.

I stood when my father stood,

bowed my head when my father

bowed his head, sat when my father sat,

his “Amen” the sweetest and saddest

of all. Last year for the first time,

we drove to services,

my father unable

to manage the two-mile walk between home

and shul. We sat up front hoping that would

help him hear, but after the third time

he asked, “What page? What page?”

licking his finger and frantically flipping

through the prayer book like he was

looking for an important number

in an outdated phone book,

I was relieved when his head dropped

to his chin, then mortified once more

when he began to snore so loudly

the rabbi threw me a look

and I took my father home. I know God will

forgive my poor aged and aging

father for not attending temple

on this Day of Atonement but I don’t know if the same God

will forgive me for not knowing

what’s best: to pray or not to pray

for the Book of Life to be inscribed

at the start of the new year

with my father’s holy name

underneath my own

“My Mother Is at the Bridge”

table with Loretta, Gert

and Pearl, when my father

finds his way to Heaven.

“Sit down, dear,” she says,

patting the seat beside her

and barely looking up from the hand

she’s been dealt. “The game is

almost through.” But my father is

too overcome to sit. He stands

and stares at his beloved, free

of wheelchair and oxygen tank

happily puffing away

on a Chesterfield King

held between two perfectly

manicured fingers, sipping

a cup of Instant Maxwell

House, leaving a bright red

lip print on the white china cup

her hair the lovely chestnut brown

it was the day they met,

her face free of worry

lines, the diamond pendant

he bought her on their first trip

to Europe glittering

against her ivory throat.

She looks like the star

of an old black-and-white movie

who would never give him

the time of day but somehow

spent 63 years by his side.

“I missed you,” my father

tells my mother, leaning down

to kiss her offered cheek.

“Of course you did,”

says my mother, who always

knows everything.

She plays her cards

right, and after Loretta and Pearl

and Gert fold, she stands to let

my father take her in his arms

and in their heavenly bodies

they dance.

“Without Warning My Father,” “When My Father Wakes Up” and “My Mother Is at the Bridge” copyright © 2021 Lesléa Newman (Headmistress Press, Sequim, WA). Used by permission of the author.