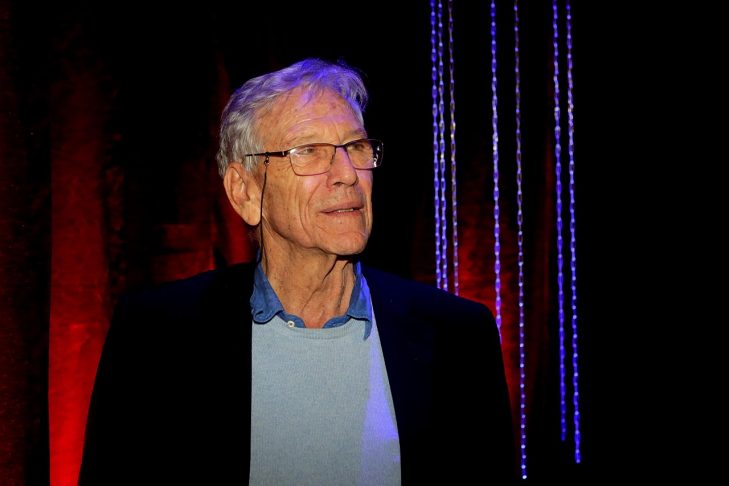

For over five decades, Amos Oz was a poetic prophet who illuminated Israel’s social and political complexities, as well as the divisions that have come to define the world. Born as Amos Klausner in Jerusalem in 1939, Oz changed his name when he was 14, two years after his mother’s suicide. The word “oz” in Hebrew means “strength,” and Oz cultivated his strength when he left Jerusalem as a teenager for a kibbutz in central Israel. Although he grew up in a bookish right-wing family, he was a committed Labor Zionist whose craggy good looks epitomized the rugged new sabra. His dovish politics also infused his work, and his characters’ complex feelings about Israel often reflected his own.

On Friday, Dec. 28, 2018, Oz’s daughter and sometime collaborator, the historian Fania Oz-Salzberger, announced her father’s death on Twitter. “My beloved father,” wrote Oz-Salzberger, “passed away from cancer…after a rapid deterioration when he was sleeping at peace, surrounded by the people who love him. To those who love him, thank you.”

The tributes immediately poured in. Israel’s President Reuven Rivlin called Oz “our greatest writer” and “a giant of the spirit.” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, with whom Oz strongly differed on a variety of issues, said Oz was one of the greatest authors in Israeli history. He noted that Oz’s contribution to Hebrew language and literature was invaluable.

Oz’s literary career spanned over 50 years across 30 books, and he was the closest figure that Israel had to a national treasure. He was not only one of Israel’s most acclaimed writers and its most successful literary export, he was also one of the country’s most decorated writers. He was winner of the Israel Prize, the country’s highest civilian prize, and Germany’s Goethe Prize. He was also a perennial candidate for the Nobel Prize in literature.

Although he mostly wrote fiction, much of it centered on kibbutz life, his masterpiece was arguably a memoir, “A Tale of Love and Darkness.” The book is the story of Oz’s 1940s Jerusalem boyhood, as well as his early years on the kibbutz. In 2015, the actor Natalie Portman directed the book’s film version and played Oz’s mother, Fania.

Two decades ago, I had the honor of interviewing Oz about his most openly autobiographical novel, “Panther in the Basement.” The 12-year-old narrator recounts the summer that he befriended a British soldier just before Israel’s independence in 1948.

During our talk, he elaborated on what he described as the “literary kashrut” he practiced to distinguish his fiction from his essays. He wryly noted: “When I am full of rage and anger, I write an essay. I write for rage and nothing else. In a different mood I might write a story. On my desk I have two simple ballpoint pens. I have them for symbolic reasons. One is for stories and the other is for telling government what to do or where to go.”

Oz was an equally prominent peace activist who advocated for a two-state solution. He was a founding member of Peace Now, where he noted he belonged “to the more pragmatic and prosaic wing [of the organization]. I have never been pro-Palestinian. I have never said that Israel was the bad guy. I simply advocate for a reasonable compromise to stop the bloodshed resulting from two natural movements with powerful claims.”

Oz’s Zionism, however, was complicated. After serving in the army during 1967’s Six-Day War, Oz and a colleague set out to capture their fellow veterans’ complicated feelings about capturing the territories. Oz traveled to kibbutzim across the country with a reel-to-reel tape recorder. The recordings were the subject of a recent documentary called “Censored Voices.” Early in the film, Oz asserted that the recordings were not intended to serve as a “victory album.”

Yet Oz supported Israel’s position in a number of conflicts, including the second Lebanon war and the Israel-Gaza conflict in 2014. In a 2017 interview, Oz said he supported the United States’ move of its embassy to Jerusalem. “Every country in the world should follow President Trump and move its embassy to Israel,” he said on German television. “At the same time, each one of those countries ought to open its own embassy in East Jerusalem as the capital of the Palestinian people.”

When we spoke, Oz affirmed his faith in the Oslo Accords, but acknowledged they needed modification. His analysis of the situation turned out to be eerily prescient. “Here are two families living in the same house who don’t intend to move out,” he said. “You have to have semi-detached units. It’s a Chekhovian compromise as opposed to a Shakespearean one. In Chekhov everyone is unhappy, melancholy, but still alive. In Shakespeare the stage is filled with dead bodies.”

His most recent book, “Dear Zealots: Letters From a Divided Land,” directly addressed fanaticism, a subject that preoccupied him in recent years. In “Dear Zealots,” Oz began with a rhetorical question that echoed a previous slim book of essays he published 16 years ago titled “How to Cure a Fanatic.” Bearing in mind that fanaticism drives Israel and indeed the Middle East’s political and social dilemmas, he asked, “How does one cure a fanatic?” He declared that one could only be immune from fanaticism when “there is a willingness to exist inside open ended situations that…cannot be unequivocally settled.”

In “Dear Zealots,” Oz also reconsidered “Panther in the Basement.” He wrote, “The boy narrator…begins the story as a Zionist fanatic afire with his sense of righteousness, but within weeks he learns, to his astonishment, that there are things in the world that can be seen one way but can also be seen in a completely different way.”

Oz wrote later in the book that he was fearful for his country’s future, yet he loved its intricacies and even its foibles. He declared:

“I am afraid of the fanaticism and the violence which are becoming increasingly prevalent in Israel, and I am ashamed of them. But I like being Israeli. I like being a citizen of a country where there are eight and a half million prime ministers, eight and a half million prophets, eight and a half million messiahs. Each of us has our own personal formula for redemption, or at least a solution. Everyone shouts, and few listen. It is never boring here. It is vexing, galling, disappointing, sometimes frustrating and infuriating, but always fascinating and exciting. What I have seen here in my lifetime is far less, yet also far more, than what my parents and their parents ever dreamed of.”