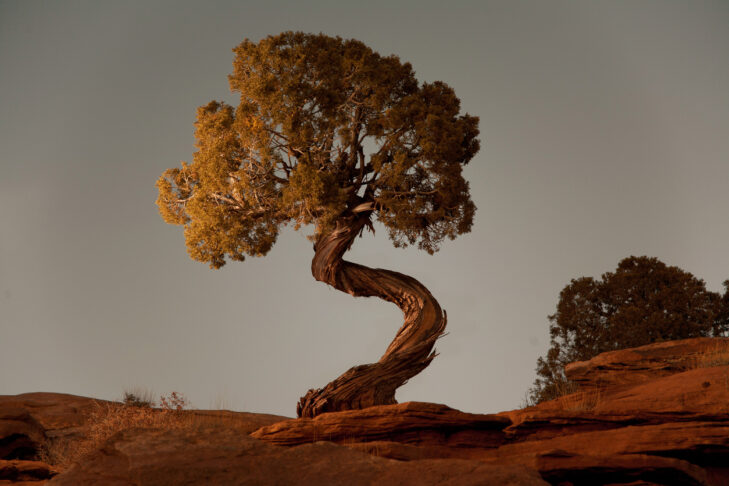

The Book of Ecclesiastes says, “A twisted thing that cannot be made straight, A lack that cannot be made good” (Ecclesiastes 1:15). If we were looking for people who exemplify this teaching, surely the Israelites in the wilderness would be good candidates. Yet again in this week’s parasha, Korach, we see confirmation of them as a “stiff necked people” (Exodus 32:9), the appellation God gives them after their stunning apostasy in making the Golden Calf. The Israelite leaders Korach, Datan and Aviram reject Moses and Aaron, implicitly questioning and turning away from God, and trigger widespread turmoil and mutiny among the people as a whole.

Over and over again after being freed from slavery, the Israelites prove incapable of leaving behind their slave mentality and inhabiting a new way of life according to God. Understandably, they have become so twisted by their experiences in Egypt that they cannot be made straight, their lack cannot be made good.

Or can they?

The Torah tells us very little about the roughly 38 years the Israelites spend wandering in the wilderness after Korach’s rebellion and after they had been condemned to die in the wilderness in last week’s parasha. We move essentially straight from the rebellions almost four decades into the future when the generation of slaves has died out and their children are at the threshold of the Promised Land.

However, if we listen closely to this silence, we can hear something extraordinary about our ancestors and their capacity for transformation and heroic action.

One thing we can clearly hear in their persistent footsteps is resilience. Despite the trauma of being told they could not enter the Land of Israel, the Israelites did not abandon the project and path of a new way of life according to God, profoundly evidenced by this persistent, decades-long trek.

In her TED Talk on grit or resilience, Angela Duckworth, the author of the best-seller “Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance,” defines resilience as “passion and perseverance for very long-term goals … Grit is sticking with your future, day in, day out, not just for the week, not just for the month, but for years, and working really hard to make that future a reality.”

Our ancestors’ resilience is particularly noteworthy because they had no future, at least not personally. Their fate was to die in the wilderness. But they had a future in their children, the next generation. The motivating future driving them onward through the wilderness was their children’s future.

The generation of slaves dedicated their lives to their children’s future, but they must have been deeply aware that a better future is only a possibility; it is not a given. No one knew this better than them. After all, if the generation that witnessed the plagues in Egypt, the parting of the sea and God’s revelation on Mount Sinai could go astray, so too could their children.

Which means that their mission, to get their children to the Promised Land, is not about simply keeping their children alive, it is about education. They must raise their children to live well, to live lives of meaning, to live according to God, exactly the kind of people they were not able to be.

Deuteronomy 11:19 says:

וְלִמַּדְתֶּ֥ם אֹתָ֛ם אֶת־בְּנֵיכֶ֖ם לְדַבֵּ֣ר בָּ֑ם בְּשִׁבְתְּךָ֤ בְּבֵיתֶ֙ךָ֙ וּבְלֶכְתְּךָ֣ בַדֶּ֔רֶךְ וּֽבְשָׁכְבְּךָ֖ וּבְקוּמֶֽךָ׃

Teach them [meaning the paths of our people, the ways of God] to your children, speaking them in your homes and when you are out in the world, when you lie down and when you get up.

The Hebrew of the first half of the verse is fascinating though in its ambiguity. It says, literally:

וְלִמַּדְתֶּ֥ם אֹתָ֛ם אֶת־בְּנֵיכֶ֖ם

Teach them to your children

לְדַבֵּ֣ר בָּ֑ם

To speak them, implicitly to make them the basis of your life.

Who is the subject of the verb לְדַבֵּ֣ר? To speak? Who will learn to speak these ways of being in all areas of life? Is it the children, as you might expect, who are supposed to become fluent in the traditions? Or is it the parents who are doing the teaching that become fluent in them as they teach? The Hebrew is unclear.

The answer, of course, is both. In the act of teaching, if we take our work seriously, we internalize our subject matter more deeply. More than that, we as teachers must be transformed if we want to maximize our chances of success. The next generation’s fluency in and commitment to the values we hold dear is dramatically impacted by our own relationship to them and the extent to which we live what we preach. As the educational theorist Parker Palmer writes in his book “The Courage to Teach,” “Good teaching cannot be reduced to technique; good teaching comes from the identity and integrity of the teacher…As I teach, I project the condition of my soul onto my students, my subject, and our way of being together.”

In the silence of the 40 years of wandering, in addition to hearing our ancestors persevere for the sake of future generations, we can hear transformation. We hear the Israelites internalize the faith they could not muster previously for the sake of and through the process of teaching their children to have that very faith. We hear the twisted thing become straight.

As we live through one of the most challenging times many of us have ever encountered, our collective retrenchment to partisanship in the face of a global pandemic and the confrontation with systemic and violent racism can make it seem as if our society is a twisted thing that cannot be made straight. Let us take hope from the Israelites in the wilderness, who struggled, failed, persevered and ultimately led their children to a better reality.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE