My grandmother, Inga Protentis, arrived at Ellis Island at 6 years old, after a chance escape from Nazi Germany. Inga arrived at Ellis Island in 1939 with her mother, leaving her father behind, imprisoned in Dachau and, later, Buchenwald. As the youngest in the family, when circumstances grew dim for German Jews, she was too young to leave Germany for Palestine or America, like her siblings. Due in part to the daring act of a Nazi soldier, her mother’s careful maneuvering and the generosity of unknown relatives in the United States, Inga and her mother survived. On Jan. 27, as we recognize International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Inga reflects on her journey to Ellis Island and her life in America.

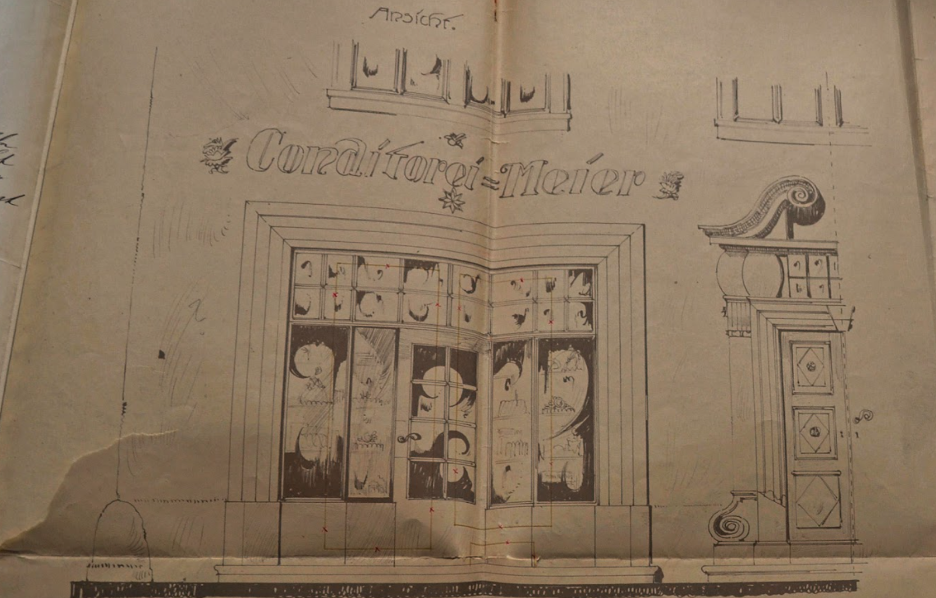

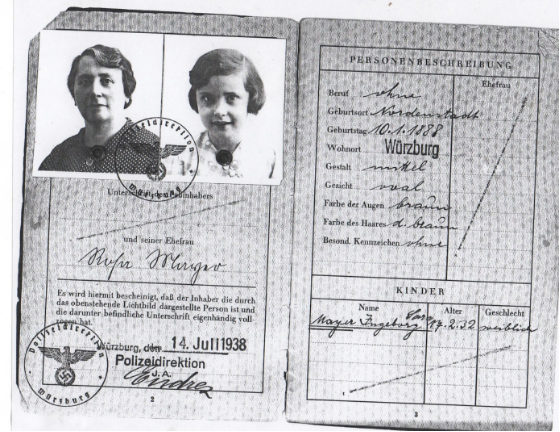

Inga was born in 1932 to a wealthy family in Würzburg, Germany. Her father was a master baker and owner of Conditorei Meier, a prosperous café and restaurant that he and his wife, Rosa, co-managed. Max was a generous man who often fed broke college students for free, asking the students, in jest, to pay him back when they became successful doctors or lawyers. He was also one of the earliest Jews to speak out against Hitler and, as a result, in 1933 he was arrested at his home and sent to Dachau. Inga remembers seeing him only once more in Germany, in passing at the train station in the middle of the night as he was being transferred from Dachau to Buchenwald.

As Inga recalls, her mother, Rosa, was a woman “daring and before her time,” one that Inga says she owes her life to. After Max’s arrest, Rosa swiftly began preparations for the worst. Night after night, Inga would be awoken to practice retrieving jewels from their home’s attic, reciting the numbered beams where her mother hid them. In case of an emergency, Inga was to retrieve them and travel to a predetermined neighbor’s home. Her mother used her wealth to gain information on Max and possibly pave a path for his eventual escape to the United States, visiting the local Gestapo headquarters with an item of value, a payment disappearing with the swap of a handshake.

Before November 1938, Rosa Mayer took in other Jewish families in need of safe haven. On Kristallnacht, Inga still vividly recalls the pounding on the large castle-like wooden door, the Gestapo’s boots on the marble floors and the sounds of screaming as the other Jewish families were being shot and killed. Inga and Rosa hid in a distant bedroom, blocked the door with furniture and as the screams got louder and closer, Rosa held Inga close and said, “Ingeborg, we’re going to die tonight.” But sometime the next day, a neighbor knocked on the door assuring them that it was safe to come out. Later, they learned that the head of the local storm troopers had been a customer of Conditorei Meir, one that was fed for free. He intervened as the troops approached Inga and Rosa’s hiding spot, denying that there was anyone left in those rooms, potentially sparing their lives.

After suffering unspeakable horrors at the hands of the Nazis at a holding camp, Inga and her mother made it the U.S. in 1939 a few months before her seventh birthday. Inga remembers the silence and weeping of the families on the ship as the Statue of Liberty came into view. It was not until the 1990s that Inga discovered that a relative in Mississippi paid the required fees to the U.S. State Department to sponsor their immigration.

Settling in the Bronx, Inga enrolled in school knowing no English, excelled in academics and later got a job at Endicott Johnson Shoes in Manhattan, where she met her husband, Sam Protentis. Inga and Sam eloped on their lunch break in 1946 before moving to Massachusetts. Settling on the South Shore, she became an advocate for language-emersion programs, served on school boards, established a children’s safety program, advocated for women’s rights through the National Organization of Women, volunteered at battered women’s shelters and spoke in numerous classrooms about the Holocaust.

Despite the horrors of being a child survivor of the Holocaust, on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, weeks before she celebrates her 90th birthday and her 84th year in the U.S., she reflects on this commemoration. She says that kindness and generosity, like that of her relative in the U.S. and this Nazi soldier, should be constant, as we have no idea how acts of kindness can change someone’s life. She’s so thankful she was able to come to America and implores Americans to be compassionate and welcoming to people who want to come and make a life for themselves. Finally, Inga says that to avoid another Holocaust, it is imperative to give back, to participate civically and to always speak about events like the Holocaust as a means to educate others about the horrors of religious intolerance and genocide.

In 2012, Inga was honored in Würzburg, Germany, along with other living Holocaust survivors, and in 2016 she shared her story with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. She and her husband just celebrated 70 years of marriage and still happily reside on the South Shore.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE