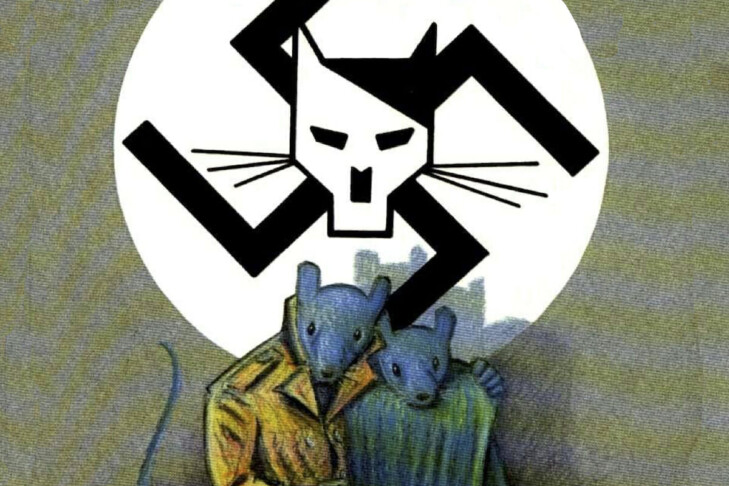

When “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” was published in 1986, it made an indelible impression. No one had ever seen anything like Art Spiegelman’s Holocaust fable, in which he depicted Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. The graphic novel was, as its jacket conveyed, approaching “the unspeakable through the diminutive.”

At first glance, that might sound reductionist. But take in Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book and it becomes obvious he transformed the comics format into an opus that takes on the gravity of an intense, explicit depiction of the Nazi genocide against the Jews.

On one level, “Maus” is Spiegelman’s family story of survival. On another level, it documents how the Holocaust continues to impact second- and third-generation survivors. When the book first came out, The New York Times book critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt was clearly taken with Spiegelman’s work, commenting, “…the medium is the message. By claiming the Holocaust as a subject fit for comic-book art, Mr. Spiegelman is saying that the children of the survivors have a right to the subject too and have their own unique problems, which are comic as well as tragic.”

Related

Spiegelman said that writing and drawing panels for “Maus” took him 13 years to come together. As he worked on the book, he did not imagine a middle-school audience reading about the Spiegelman family’s Holocaust experiences. Prior to the McMinn County decision, he said he entertained thoughts about whether kids should be reading “Maus” at all. “The issue is, I wasn’t ever thinking about it as a learning tool,” he said. “I never was trying to write ‘Auschwitz for Beginners.’ I wasn’t really trying to do anything other than tell a story that felt compelling enough to devote whatever it took to make it work, to both understand and, maybe the right word is, share.”

After Spiegelman’s book was banned, critics of the decision quickly pointed out that McMinn County’s actions did not have any effect on protecting eighth graders from exposure to traumatic material. In fact, any one of those kids can pull out their smartphones and instantly delve into “Maus’” subject matter. Spiegelman explained: “It’s important to point out maybe that [comics] was the first medium aimed directly at kids that they could get at by themselves. Ten cents would get you there, and that’s where the panic started coming in. So, I believe this is all about parents wanting to control their kids in the guise of protecting them.”

There was also the issue of contextualizing history. Without a teacher guiding them, would McMinn County’s eighth graders understand why the Holocaust was an unprecedented and devasting rupture in modern history? Would they understand that referencing the Holocaust casually—using descriptions like “Nazi” for a person they don’t like or calling school a “concentration camp”—is wholly inappropriate? Awareness is a superpower, and in the case of the Holocaust, it is a deterrent to it happening again.

At the heart of the school board’s decision is the troubling symbolism of banning Spiegelman’s book. The very act can conjure images of Nazis throwing Jewish books into bonfires. Spiegelman pointed out the unthinkable happened when copies of “Maus” were recently burned in Nashville. “Burning books [is readjusting] our curricula to terrify librarians and book readers and teachers,” he said.

Book-banning is also fear-mongering. However, it is more frightening not to teach the Holocaust at a time when white supremacy is surging and antisemitism is skyrocketing. Spiegelman noted, “I was interested to learn that until last year, McMinn County also thought this was possible on an eighth-grade reading level, and I am distressed to find that that has changed in the midst of strong political headwinds.”

For Spiegelman, writing and drawing “Maus” was about “making something that puts me in an I-thou relationship with the reader; I’m being as open about my thoughts as possible. They’re not sanitized, they’re not simplified and I’m proud of that. This was another thing where one of the board members blurted out how horrible it was to see hanged mice and children being killed.”

If there is a glimmer of a silver lining in this story, it is that Spiegelman’s book will be sent free of charge to McMinn County students from three bookstores in Knoxville and Nashville. Similarly, donations of the book are arriving in McMinn County’s library.

For Spiegelman, the attention paid to banning “Maus” has also sparked necessary and related discussions about persecuting the marginalized. He said that although “Maus” focused on the Nazi genocide of the Jews, it was not only about Jews. “This is about othering,” he said. “And what’s going on now is about controlling—controlling what kids can look at, what kids can read, what kids can see in a way that makes them less able to think.”