Multimedia artist Karen Frostig will speak to the United Nations General Assembly on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Jan. 27, 2023, about her new project, “Locker of Memory.” In this latest work, Frostig memorializes the 4,000 Jews murdered in Jungfernhof, Latvia’s first concentration camp established under Nazi occupation, located three miles outside Riga and a concentration camp that is often overlooked in Holocaust history. The series of memorials will consist of four panels corresponding to the four transports to Jungfernhof from Nuremberg, Stuttgart, Vienna and Hamburg.

Frostig’s grandparents, Moses and Beile, were deported from Vienna, Austria, to the Jungfernhof concentration camp in late 1941. Frostig is certain her grandparents died in the first two months at the camp of inhumane treatment, starvation, cold, or indiscriminate shootings by the Kommandant in charge. Anyone over age 50 still living was murdered on March 26 in a large forest massacre. When Jungfernhof largely shut down in 1943, most inmates still enslaved were transferred to other camps. The camp was dismantled in July 1944, with 27 remaining survivors sent to Kaiserwald. By the end of the war, there were only 149 Jungfernhof survivors.

This summer, Frostig will create an opening ceremony at the Jungfernhof site to prepare the land for the development of a permanent memorial. Latvian, German and Austrian officials and descendants of victims will be present. The memorial will be designed to cohabitate with the bucolic public park that encompasses the site where families picnic and children play along the Daugava River. Developing a permanent memorial is a longer process that will involve raising funds and creating numerous meeting with local residents.

Frostig, a professor of art at Lesley University, creates art fueled by memories that often evoke the Holocaust and her grandparents’ murders. She recently told JewishBoston: “What strikes me about memory is that, like my work, it is by default interdisciplinary. A lot of my interests and strengths converge in my art.”

In planning and installing Jungfernhof’s memorial over these last few years, Frostig uncovered strong connections to her other art projects similarly rooted in memory. Those projects included “Earth Wounds,” which debuted in 2004 and, in retrospect, was a dress rehearsal for “Locker of Memory.” The former used Jewish burial rituals, including wrapping cut down trees in ceremonial shrouds, to mourn the 26 acres of land sacrificed for real estate development near her home in Newton.

“I saw these huge tree stumps on the [former] grounds of Andover Newton Theological School and associated them with photographs of bodies in Riga on a hillside near the ocean,” Frostig recalled. “In mourning these trees, I realized that making a grave for green trees and ritually shrouding them was about coming to terms with the mass grave where my grandparents were buried.”

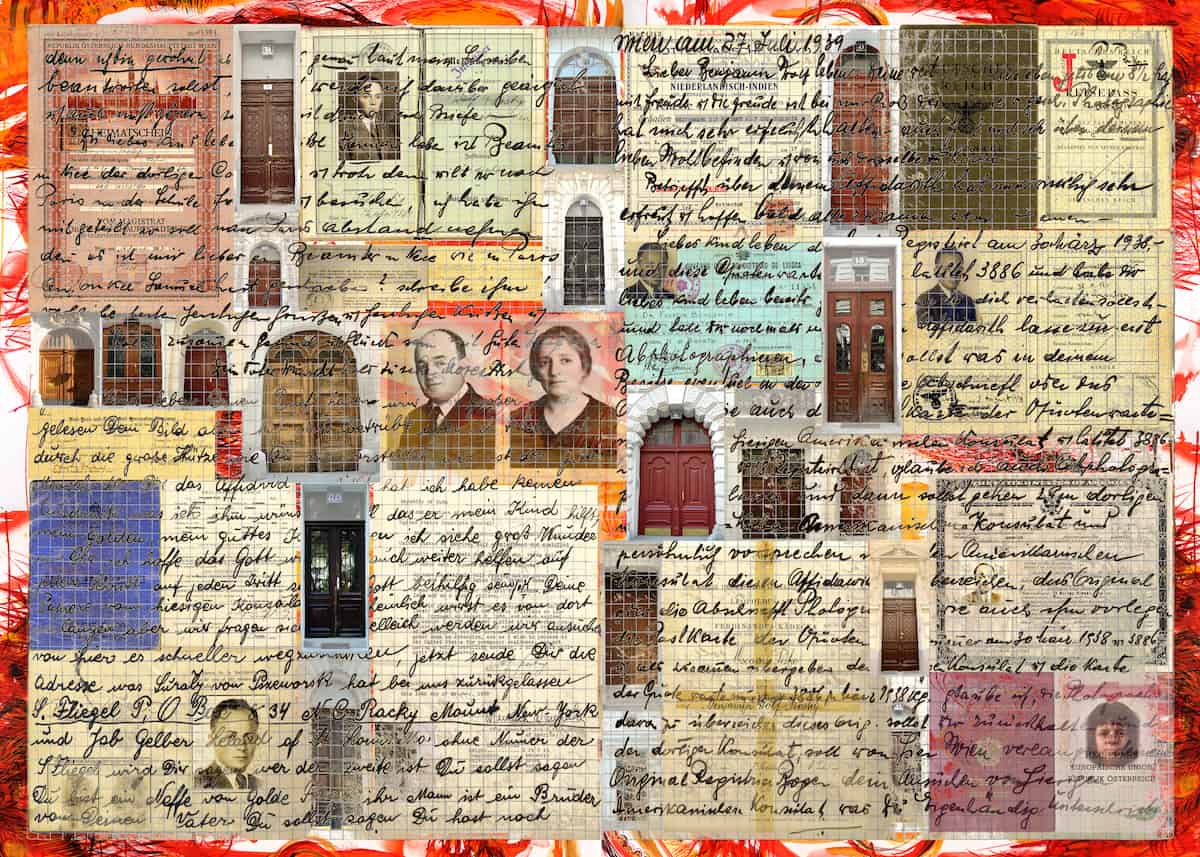

Frostig’s “Exiled Memory Project” conveys her grandparents’ tragic story through a series of panels displaying correspondence between Frostig’s grandparents and her late father, Benjamin Wolf Frostig, at the beginning of the Holocaust. The exhibit, installed in 2008 at the University of Vienna’s law school to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Anschluss also presents her grandparents’ passport photos (which were never used)—the only surviving images of them. Her father earned his law degree and a Ph.D. in law and economics at the university in 1936.

Benjamin was arrested shortly after the Anschluss and fled Vienna six months later, launching him on a convoluted voyage that included stops in Portugal, Mexico and Cuba. During that time, his parents tasked him with acquiring visas allowing them to leave Vienna. After a series of devastating events, which ended with a Nazi spy stealing Benjamin’s identity in Cuba, time and money had run out to rescue his parents. The letters between parents and son hauntingly document their growing desperation to leave Europe.

In 2010, Frostig’s proposal to create a public art installation where the Jungfernhof camp once stood caught the attention of Latvian officials, artists and the small Jewish community in Riga. She called the work “Shelter of Peace,” a title reminiscent of the evening Hashkiveinu prayer, which asks God “to spread over us Your shelter of peace.”

Frostig said: “I wanted to make a memorial that partially evoked a sukkah. Jungfernhof was not only a place where people were murdered, but also a former agricultural estate turned into a slave labor farm. The sukkah partially re-enacts what the camp once was.”

Related

Among Frostig’s goals in “Locker of Memory” is to bring forward what had been thought was lost to history. For example, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s online encyclopedia does not have an entry for Jungfernhof. In addition, Yad Vashem’s mention of the camp on its site is mostly footnoted. Frostig guessed that the camp largely flew under the radar because there was no documentation due to its early closure.

Rather than think of Jungfernhof as neglected, abandoned or forgotten, Frostig considers the camp “unremembered.” “It’s not accurate to think of Jungfernhof as forgotten because people have remembered it,” she said. “Survivors wrote memoirs and sat for interviews with Yad Vashem and the Shoah Foundation.”

However, she acknowledged that she may not have known about her grandparents’ deportation to Riga if she had not discovered a stash of documents her father had saved. To add to that family archive, a cousin sent her the 70 letters she featured in “Exile of Memory.” She noted the correspondence allowed her to memorialize “a transnational, inter-generational conversation about the Holocaust.”

Another crucial goal for Frostig was to locate the camp’s mass grave, where she is almost certain her grandparents were buried. A branch of archeology specializes in recovering DNA and artifacts lost in the Shoah, and Frostig expects that the archeology’s non-invasive technology, such as ground-penetrating radar, will be key in locating Jungfernhof’s mass grave as early as next summer.

About her upcoming speech at the United Nations, Frostig said the timing feels especially poignant given the situation in Ukraine. And, like Frostig’s art, the presentation will integrate memory, personal memoir, and cultural and Holocaust history.